Mellor and Ludworth were part of the Royal Forest of the Peak but Marple and Wybersley were also in a royal forest, the Forest of Macclesfield. An early development, it was established prior to 1160 and, at its height, it covered about 80 square miles from Chadkirk in the north to just north of Congleton. It was contiguous with the Royal Forest of the Peak with the River Goyt on its northern and western boundary and to the south the River Dane marked its limit. The western boundary followed a series of roadways.

Beginning at Rodegreen, just to the north of Congleton, it passed through Gawsworth, Prestbury and Norbury Low to the “stream of Bosden.” The exact location of Norbury Low is uncertain but presumably it was part of Norbury. The stream of Bosden, however, has been positively identified as Ochreley Brook and Poise Brook which flow from Torkington through Offerton to the Goyt. The forest boundary does not follow the stream at this point but but crosses Salter’s Bridge and joins the Goyt at Otterpool Bridge. There is speculation that this western boundary may have followed a single Roman road rather than a series of roadways but there is no definitive proof. If it did exist, the Roman road would probably have run from a military site at Astbury near Congleton, to the Roman fort at Castleshaw near Oldham, climbing over Werneth Low after crossing the Goyt.

Locally it can be seen that the Forest of Macclesfield included all of the township of Marple and much of Norbury and Bosden, together with the greater part of Torkington.

[click the image for larger image]

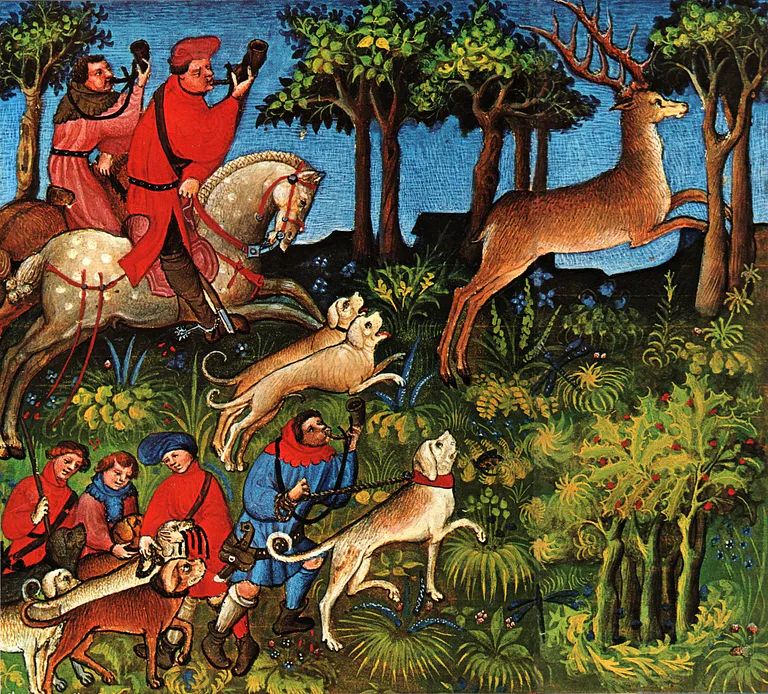

These boundaries encompassed a rather more fertile tract of land than the High Peak but it was still good hunting territory, particularly for deer. It came under Forest Law, like the Royal Forest of the Peak and had a similar structure and hierarchy of organisation. Although Macclesfield Forest came under the general title of royal forest it was not directly under the control of the king, although he was obviously the ultimate authority. Instead it was a hunting preserve of the Earls of Chester. This title represented a very powerful role in medieval England as Cheshire was a county palatine, an area ruled by a hereditary noble enjoying special authority and autonomy from the rest of the kingdom. This title was usually granted to districts on the periphery of the kingdom where there was potential danger from invasion or rebellion. The nobleman had a quasi-royal prerogative within a county - the district ruled by a count or an earl.

After the Norman conquest of 1066, William I made Cheshire a county palatinate and put one of his close followers in charge. The first appointment proved a disappointment so in 1170 Hugh d’Avranches was given the title. This title stayed in the family through seven generations, proving their loyalty and capability to the kings. It is not known exactly when the Forest of Macclesfield was created but it was definitely in existence by 1160 as it was under Forest Law by that date. It was probably created by Henry II when he came to the throne in 1154. The Earl of Chester at that time was Hugh de Kevellioc, the son of Ranulf de Gernon, a baron who had fought hard and long for Henry’s mother, Matilda, during the years of the Anarchy.

However, it was a not to stay under the control of the family for ever. In 1237, when the last male died without issue, Henry III intervened and decided that the earldom should be annexed to the crown. From that date onwards, with a very brief interregnum when Simon de Montfort became Earl, the Earldom of Chester has always been held by the King’s eldest son, the Prince of Wales. The Forest of Macclesfield was a royal forest in all but name.

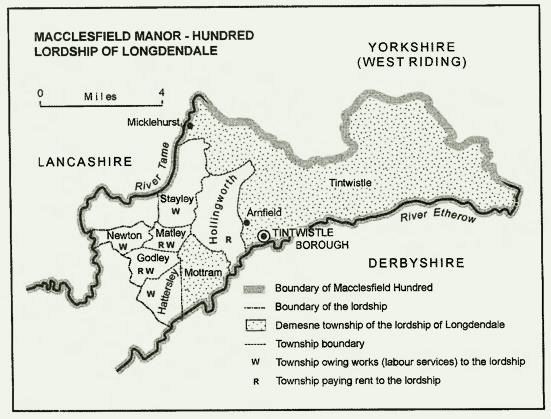

At the time of Domesday (1086) the area was lightly populated with hamlets and small villages but large areas were not cultivated. Marple and adjacent areas lay within the Hamestan hundred though it later became known as the Macclesfield hundred after its administrative centre.  The hundred of Macclesfield [click the image for larger image]

The hundred of Macclesfield [click the image for larger image]

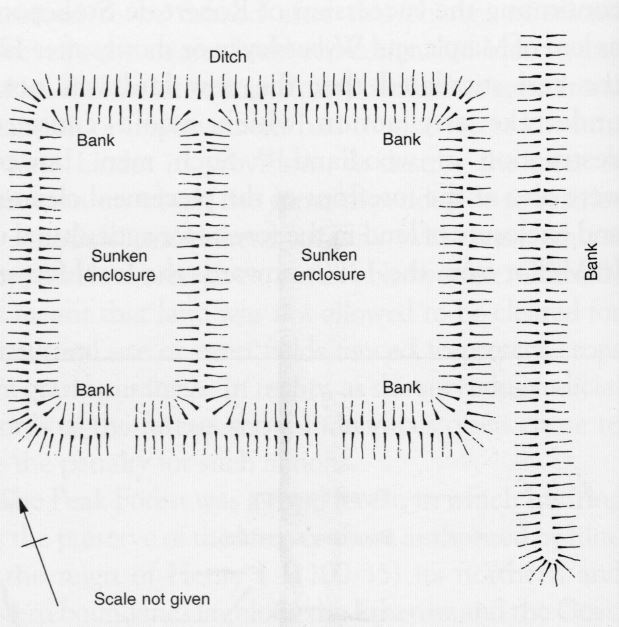

There was extensive tree cover but it was by no means a forest in the modern sense. The hunting of deer was common everywhere and Domesday records deer ‘hays’ (enclosures) in the woodlands of ‘Bretberie’ (Bredbury), ‘Bramale’ (Bramhall), ‘Nordberie’ (Norbury) and ‘Cedde’ (possibly Chadkirk but more likely to be Cheadle.) It is thought that deer were driven into these enclosures to allow inspection of the herd.

This substantial earthwork within the deer park of Bramall Hall is thought to have been used to manage herds.

This substantial earthwork within the deer park of Bramall Hall is thought to have been used to manage herds.

There were settlements within the Forest from when it was first established whereas the Peak Forest was much more sparsely settled. The main settlements within the northern part of Macclesfield Forest were, as well as Bramale, Bretberie and Nordberie named above but also Rumelie (Romiley), Warner (Werneth) and Laitone. Laitone is thought to be Leighton which is part of Hawk Green but in this context might have referred to the whole manor of Marple. The Macclesfield Hundred extended north of the Etherow, as far as the River Tame but these townshipsbut these townships, shown below, were not part of Macclesfield Forest.

All of these royal forests were subject to assarting - the claiming of areas of land for agricultural use. It was always illegal in theory but often the enforcing bodies turned a blind eye to it as fines for the offence could prove a useful source of revenue. In the Macclesfield Forest the gradual encroachment on the forest proper seemed to start earlier and was more extensive than in many other royal domains, particularly the Peak Forest adjacent to it.

All of these royal forests were subject to assarting - the claiming of areas of land for agricultural use. It was always illegal in theory but often the enforcing bodies turned a blind eye to it as fines for the offence could prove a useful source of revenue. In the Macclesfield Forest the gradual encroachment on the forest proper seemed to start earlier and was more extensive than in many other royal domains, particularly the Peak Forest adjacent to it.

Responsibility for policing the forest could be delegated. For example, the barons of Stockport were given the manor of Marple and Wybersley in return for providing a forester. When, in the early thirteenth century, Robert de Stokeport granted this manor to his sister Margaret and her husband, William de Vernon, the obligation of ‘forest service’ was also passed on to them. However, the individuals entrusted with upholding forest law were themselves subject to its restrictions. When the earl of Chester confirmed Robert de Stokeport as the lord of Marple and Wybersley he stipulated that the new lord was not to undertake any action which would cause the destruction of woodland. Despite this explicit instruction, these secondary officials were often at the forefront of piecemeal clearance and enclosure of land for agricultural use. In 1249 Richard de Vernon is reported to have reclaimed ‘a large piece of land and wood’ in Torkington, just beyond Torkington Brook, which formed the boundary with Marple.

A generation later, in the 1280s, small parcels of land were reported to have been enclosed by men named as Hugh de Hephals, Thomas de Worth, Hugh de Bosden, Richard de Bosden and Robert ‘the cook’. The geographic names give a clear indication of where these people lived but the last name, Robert the cook, is particularly interesting as it shows that some of these clearances were carried out by men who had relatively low positions in society. Sometimes they would erect houses or other buildings to demonstrate a more permanent possession. In most of these cases, once a fine had been imposed, the improvements were allowed to remain.

Sometime the clearance of the forest was conceded as a right, usually involving men of higher social status or more power. In 1221 the earl of Chester granted Richard de Vernon an additional piece of land described as ‘the wood as far as the Bluntesbroc (Bollinhurst Brook). By the same charter de Vernon was given the freedom to clear land in the woods of Marple and Wybersley ‘wherever he so wished.’ The charter did not give him complete licence. The earl reserved the right of ‘venison’ under which any action which might impede the movement of deer was still an offence. Nevertheless, the concession that the natural habitat of the deer might be freely swept away was an important turning point in the land use in this forest.

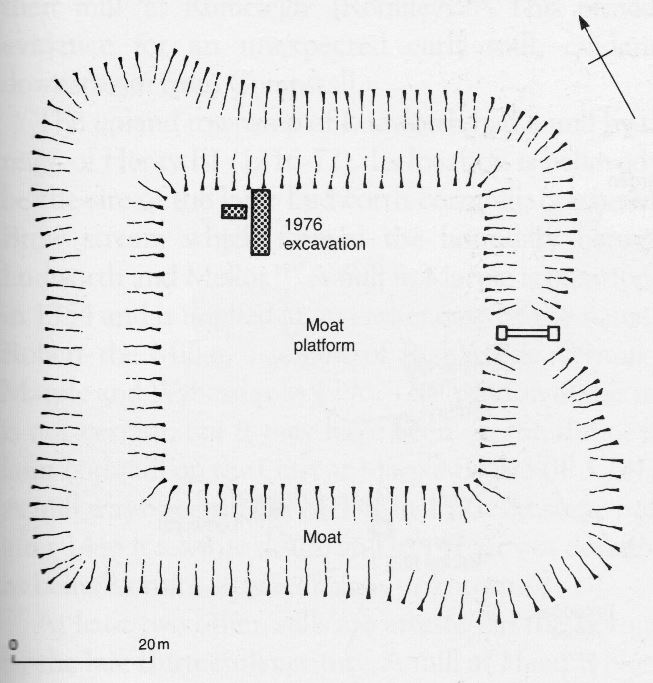

A century later, in the mid-fourteenth century, John de Legh, a forceful and aggressive member of the gentry, removed sixty acres of woodland in Torkington. As part of this clearance he built a moated house on the site now known as Broadoak Moat which can be examined in more detail at

A century later, in the mid-fourteenth century, John de Legh, a forceful and aggressive member of the gentry, removed sixty acres of woodland in Torkington. As part of this clearance he built a moated house on the site now known as Broadoak Moat which can be examined in more detail at

Broadoak Moat

In 1398 a huge tract of land was taken out of the forest when Piers Legh was granted Lyme Hanley, 1400 acres of open woods and hearth. This was the origin of Lyme Park. A knight, Sir Thomas Danyers, had saved the Black Prince, son of Edward III, from capture by the French at the battle of Crécy in 1346. At the time the king had awarded Danyers a cash sum but with the promise of a gift of land. This gift was made fifty years later, not to Danyers himself but to his grand daughter Margaret, the wife of Piers Legh. Although the Black Prince had died in 1376 the family was held in high regard as his widow had made Sir Piers a bailiff of the forest in 1378. Lyme Handley did represent a change of ownership but not necessarily a change of land use as the Leghs wanted to use this land as a deer park. At the time most of their land was in present day south Lancashire and this was their main house. The Lyme estate was for recreation and not for cultivation.

In contrast, the Black Prince himself had disafforested a large area of Macclesfield Forest for commercial purposes. Between 1354 and 1376 when he died, his stewards had built up a commercial enterprise breeding and selling cattle, both cows and oxen. At its maximum the total herd was over 700 head - a sizeable enterprise at that time. The cattle were kept in three enclosed pastures. The first was Macclesfield park which had grazing land and areas for growing hay, together with various buildings to shelter the cattle in winter. A second area was Midgley, about four miles south east of Macclesfield, which was an area of meadow and enclosed pasture in Wildboarclough township. This area had been a vaccary (dairy farm) since at least the first half of the thirteenth century. The third area was Harrop, a hamlet in Rainbow township, about two miles north east of Macclesfield. Like the park this was enclosed by a palisade. In addition there were other areas that provided hay so in effect a large area, probably over 1000 acres, around Macclesfield was taken out of forest use.

Drawing of cows shown on a medieval manuscript

It would seem that even in its early days Macclesfield Forest was not regarded as sacrosanct for deer and boar habitat but was frequently subject to assarting. By the time of the seventeenth century when all royal forests were coming to an end Macclesfield Forest had essentially ceased to exist. In 1606 Edward Stanley sold off his Marple estate as free holdings. In Torkington the process was more cooperative as land at Torkington Green was enclosed by the community, together with waste land near the main road to Stockport. In 1672 there were eleven freeholders in Bredbury, having bought their land from the Ardennes. There was no official disafforestation as there had been in Mellor. The Royal Forest of Macclesfield ended with a whimper rather than a bang - it just faded away.

Further Reading:

Two books which may help to explain the landscape and vegetation of our local royal parks are:-