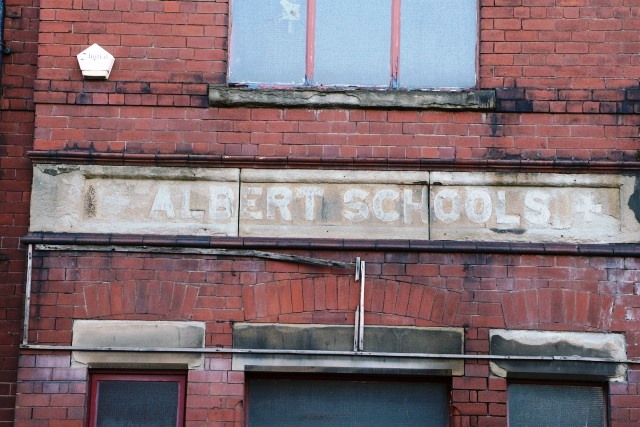

So, the Albert Schools will soon be no more. Its familiar facade has been a part of this community for 150 years so perhaps we should learn a little about it before it is gone forever. It has only been a school for less than half that 150-year history but why the name “Albert” and why “Schools” (plural)?

To answer that we need to look at the way we educated our children in centuries past.

A class photo from Albert Schools on Church Lane, probably pre-1900.

Britain, or to be more precise, England, has never put much store by education for the vast majority of its citizens. The earliest known organised schools in England were connected to the church. Augustine established a church in Canterbury in 598, and in 604 this was joined by another school at what is now Rochester Cathedral. Further schools were established throughout the British Isles in the seventh and eighth centuries, generally following one of two forms: grammar schools to teach Latin, and song schools to train singers for cathedral choirs.

As the country began to experience the industrial revolution from the mid eighteenth century there was a need for a (slightly) better educated workforce. Entrepreneurs began to chafe against the restrictions of the apprenticeship system and a legal ruling established that the Statute of Apprentices did not apply to trades that were not in existence when it was passed in 1563, thus excluding many new 18th century occupations.

Dame SchoolInformal “Dame” schools were set up to give basic lessons very cheaply but in many cases these were little better than child-minding centres. Some of the new factory owners set up their own schools to provide a focused education which would be applicable to that particular factory. Samuel Oldknow instituted such a Day School in 1793 to teach about thirty apprentices cotton picking and other specific tasks required for cotton spinning. They received rather more formal lessons on Sundays. In 1801 a teacher was paid for instructing 52 boys for 15 Sundays. For that he was paid 4 shillings and fourpence each Sunday; £3.5.0d in total. Five other boys were taught for shorter periods and the girls were taught separately but the records for this have not been preserved.

Dame SchoolInformal “Dame” schools were set up to give basic lessons very cheaply but in many cases these were little better than child-minding centres. Some of the new factory owners set up their own schools to provide a focused education which would be applicable to that particular factory. Samuel Oldknow instituted such a Day School in 1793 to teach about thirty apprentices cotton picking and other specific tasks required for cotton spinning. They received rather more formal lessons on Sundays. In 1801 a teacher was paid for instructing 52 boys for 15 Sundays. For that he was paid 4 shillings and fourpence each Sunday; £3.5.0d in total. Five other boys were taught for shorter periods and the girls were taught separately but the records for this have not been preserved.

Sunday Schools began to emerge about the same time in the 1780s, originally starting in the Gloucester area but they quickly spread. Many clergymen supported the schools which aimed to give children the “Three Rs” (reading, writing and arithmetic) and a knowledge of the bible. By 1785 250,000 children were attending Sunday school. The original curriculum started with teaching the children to read and then having them learn the catechism. The bible was the main (and probably the only) text book.

St. David's National School, St David's, Wales, circa 1885)The churches were concerned that society was changing rapidly with industrialisation and that the change from settled rural living was detrimental to the traditional practice and belief in religion. In the late eighteenth century two educationalists separately developed two similar but subtly different systems for teaching. A school master would teach a small group of brighter or older children, and each of them would then relate the lesson to another group of children. Andrew Bell, an Episcopalian priest, was instrumental in developing the Madras or monitorial system whilst Joseph Lancaster used a variant of the system called peer tutoring. The key advantage of both these systems was that they avoided the expense of assistant teachers. Neither believed in corporal punishment but some of the alternatives were, to our eyes, equally repellent such as being tied up in a sack or hoisted above the classroom in cages.

St. David's National School, St David's, Wales, circa 1885)The churches were concerned that society was changing rapidly with industrialisation and that the change from settled rural living was detrimental to the traditional practice and belief in religion. In the late eighteenth century two educationalists separately developed two similar but subtly different systems for teaching. A school master would teach a small group of brighter or older children, and each of them would then relate the lesson to another group of children. Andrew Bell, an Episcopalian priest, was instrumental in developing the Madras or monitorial system whilst Joseph Lancaster used a variant of the system called peer tutoring. The key advantage of both these systems was that they avoided the expense of assistant teachers. Neither believed in corporal punishment but some of the alternatives were, to our eyes, equally repellent such as being tied up in a sack or hoisted above the classroom in cages.

The nonconformist churches gravitated towards the Lancasterian system and the British and Foreign School Society was formed in 1808 to proselytise this method throughout the country and further afield. Not to be outdone the Church of England established the National Society in 1811 to encourage education using Dr Bell’s methods. The aim was to establish a National School in every parish in England and Wales. The schools were usually next to the parish church and named after it. Marple established its first National School at All Saints’ in 1831 and a similar school was established in High Lane in 1846.

The Congregational Church in Marple already had an informal Sunday School but in 1868 it co-operated with the British and Foreign School Society to establish a standard school in Marple. The BFSS had been working with nonconformist churches since 1808 and its Anglican equivalent, the National Society, since 1811. These two religious charities were the dominant providers of education throughout the country. The driving force behind the establishment of the Marple school was Thomas Carver, the owner of Hollins Mill. There had been many complaints that the National School (C of E) was innefficient and gave a poor quality of education. However, the date might be significant. Two years later, in 1870, the Education Act provided for the establishment of board schools to supplement those of the societies. Perhaps the establishment of the school in 1868 was accelerated because the nonconformists wanted to place a marker before board schools were proposed for the area.

Albert Schools, Church Lane

Although the school received some government grants the building belonged to the Congregational Church and the managers were ‘tenants-at-will’ of the Church. The building was named after the Prince Consort who had died in 1861 and it was known as the Albert Schools to designate its dual purpose - both Sunday School and standard school.

Thomas Carver wanted to provide a better education for children of church members and his mill workers. As an incentive, attendance at the Albert Schools seems to have ensured half-time employment at the mill. School fees were 4d per week. In 1870 Robert Whitaker was one of the schoolmasters, a 25 year old member of the church who lived in Leigh Avenue. However, he did not stay long as by 1881 he was teaching at a Board School in Mile End, London. The girls were being taught by a Miss Airey and Ellen Pye, aged 20, living at Egerton Villas, Church Lane.

A large group at Albert Schools, date unknown.

A large group at Albert Schools, date unknown.

The 1870 Education Act recognised that the state had an important role to play in education but it was not made compulsory. However, subsequent acts in 1876, 1880, 1893 and 1899 not only made attendance compulsory but expanded the responsibility of schools and gradually raised the school-leaving age from 10 to 13. All this put pressure on existing schools and the Albert Schools was found to be too small to deal with the increased number of scholars. The church gave permission for enlargement ‘provided the property did not suffer and the Day School bore the cost’ according to the church minutes. There must have been a considerable argument as eventually the church paid the bill since it owned the buildings which were used for the Sunday School and were also let to outside organisations. As with all Voluntary Schools the Church members made great efforts to raise the necessary money, but they were again faced with the need for enlargement in 1892 owing to an increase in population. £700 was required and this was raised by subscriptions from the owners of Hollins Mill and their friends, foremost among these the Carver and Hodgkinson families. While the four rooms - two upstairs and two downstairs - were being added, the children had three months holiday.

In 1896 Mr J.H.Robins was the Headmaster of the Mixed School with three Assistants and two Pupil Teachers. The Infant Mistress was Miss Dale with one Pupil Teacher. In the same year after an inspection the honour of “First Class School” was conferred by the Education Department and the school was exempted from annual inspection. An increased grant was anticipated. There were 210 Scholars in the Mixed School and 87 in the Infants. In addition to the three Rs, Geography, Drawing, Singing, Needlework, Cooking, French and Algebra were taught in the Mixed School. In 1898 another excellent report was given and the Grant was £244. “All fees in the Infant School have been abolished this year”, ends the Government Report. 1900 saw another very good report earning a grant of £241.14.3d.

The method of financing the school from the Government Grant, the children’s pence and the building costs shared with the church led to inevitable friction. Although the Deacons gave consent for the Managers to comply with the Government Inspector’s request for the playground to be asphalted in 1896, they refused financial aid from the Church funds. Another source of friction was the shared payment of the school caretaker. This was a continual source of dissension between the church and the lay authorities until 1902 when the Balfour Act set up Local Education Authorities and they assumed much of the financial responsibility for ‘Provided Schools.’ The Church Deaconate had no hesitation in deciding that the Albert School should become a ‘Provided School’ under the Act and no doubt they heaved a sigh of relief when responsibility passed to the Cheshire Education Committee in 1904.

Thought to be staff or governors at Albert Schools, but uncertain (can you help identify?)

Thought to be staff or governors at Albert Schools, but uncertain (can you help identify?)

By this time Mr Frederick Pennington, a Certificated Assistant, had become Headmaster. Born in Whitehaven, he was only 25 when he came to the school as an assistant schoolmaster but he had obviously made a mark as he was promoted to headmaster when Mr Robins died. Originally living in Norris Bank in Stockport, he moved to Norbury Field, off Bowden Lane, with his wife and young daughter when he became headmaster. Unlike his predecessor he was not himself a member of the Church: as far as the school was concerned he was responsible only to the Education Authority, and had the usual difficulties to contend with when a Sunday and a Day School used the same building. Two improvements in the school after this date were the provision of water closets for the boys in 1908 (though they were an outside facility until the 1940s), and improved gas-lighting in 1926. A room upstairs on the right was always referred to as the science room, it had a laboratory type sink and tap and gas point, all on a raised rostrum. There was obviously very little ‘hands on’ education in chemistry lessons. Mr Pennington’s first wife died and he married one of the teachers at the school, Gladys Prentice, in 1918. This would have made his job easier as, although fifteen years younger than him, she was a member of the church which would have helped in discussions with the Deaconate. However, Cheshire County was taking more and more responsibility.

Details of brickwork on the Albert SchoolsThe Albert School closed in 1931 when the Willows Senior School opened and Mr. Pennington was appointed Headmaster, taking with him from the Albert Schools those scholars of 11 years and over. The younger scholars went to All Saints Primary School.

Details of brickwork on the Albert SchoolsThe Albert School closed in 1931 when the Willows Senior School opened and Mr. Pennington was appointed Headmaster, taking with him from the Albert Schools those scholars of 11 years and over. The younger scholars went to All Saints Primary School.

The Congregational Church continued using the building for a variety of purposes. During the Second World War the school was rented by the Ministry of Labour and used from time to time to accommodate evacuees. In the years after the war the church ran a thriving youth group with many types of activity - sports teams, educational outings such as a visit to a coal mine, tiddlywinks competitions for enjoyment and, on one occasion, the whole group slept in the grounds in cardboard boxes to experience the condition of the homeless. Gilbert and Sullivan operas were put on from time to time and they were a great success for many years. The day the chimney was demolished at Hollins Mill, the rehearsals were delayed whilst the whole cast went to watch. Sunday School was held in the building and the older children were often involved in teaching the younger children, a practice that dated back to the Lancasterian system in the early days of the British and Foreign School Society.

By the late 1950s it was sold to a company making overalls but it has now finally come to the end of its useful life. It would be nice if the facade could be preserved just for old time’s sake but it has no real architectural merit so that too will probably go in the name of progress. Good bye old friend.

Text: Neil Mullineux, January 2019

Contemporary photos: David Burridge

Addendum (February 2019)

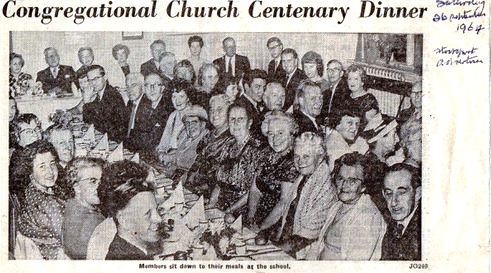

Last month’s article about The Albert Schools certainly struck a chord – well two actually! First, we have been given an original programme from a 1902 Sale of Work that was held at the Schools. As well as the many advertisements included in the programme, there is a history of the school that is invaluable and records the names of teachers and governors. Secondly, we have received a copy of a newspaper article from 1964, recording the Congregation Church centenary celebratory dinner, which was held at the schools.

Last month’s article about The Albert Schools certainly struck a chord – well two actually! First, we have been given an original programme from a 1902 Sale of Work that was held at the Schools. As well as the many advertisements included in the programme, there is a history of the school that is invaluable and records the names of teachers and governors. Secondly, we have received a copy of a newspaper article from 1964, recording the Congregation Church centenary celebratory dinner, which was held at the schools.

Thanks to Gwen Pickford for the programme and Edmund Wilkinson for the newspaper article.

Does anyone else have any memories of the building as a school or its afterlife? No one alive will have been to school there because it closed in 1931 but perhaps there are family stories about it? Do you have memories to share of The Willows, which took over from the Albert Schools?

Hilary Atkinson

Note: The Society archives contain:

Material on Albert School & National Schools:

Source: https://www.marplelocalhistorysociety.org.uk/archives/items/show/1667

1. Photocopy of photograph of Albert School 1910

2. Photocopy of Grand Sale of Work fro Albert British Day Schools, Marple : 1902

3. Typed Notes on the Albert British School 1868 - 1931

4. Gladys Swindells typed research notes : The Transfer of the Albert British Day School to the Control of the Cheshire Education Authority : Staff of the Albert Schools : Typed minutes from Marple Nation School 1953 - 1961: Handwritten newspapers reports relating to National School & Church from 1874

5. County of Cheshire Reports on Structural & Sanitary conditions of school buildings for Marple & High Lane, Marple Low, Marple Albert British schools 1902

Material on The Dame School at Turf Lea:

Source: https://www.marplelocalhistorysociety.org.uk/archives/items/show/1625

1. Typed Document : "Mrs R Howard's recollection of Mr & Mrs Taylor of Turf Lea". Author / Date unknown

2. Hand written with typed transcript of recollections following article in the Reporter headed "The Dame School of Turf Lea" Author/date unknown.

3. Newspaper article referred to in the above item "Dame School at Turf Lea" with typed transcript. Addendum: July 2019

Albert Schools

In the above article Neil Mullineux wrote "By the late 1950s it was sold to a company making overalls but it has now finally come to the end of its useful life. It would be nice if the facade could be preserved just for old time’s sake but it has no real architectural merit so that too will probably go in the name of progress. Good bye old friend."

Planning Application> for the area, 92-94 Church Road. Proposal "Demolition of existing buildings and erection of mixed use development comprising 20 apartments and A1 retail floorspace (Amended Plans)."

Sadly the demolition has occurred, photos by Hilary Atkinson & David Burridge.