Two bridges on the Macclesfield Canal in High Lane are “listed” by English Heritage. They are both interesting but not particularly noteworthy. Bridge Eleven carries the A6 over the canal so it is wide enough to almost be described as a tunnel. About 150 metres to the south Bridge Twelve curves gently as it carries the towpath over the entrance to High Lane wharf, a much more interesting feature. This is a particularly attractive bridge with a gentle curve taking the towpath over the entrance to the canal arm. The canal itself is important as one of the last narrow canals built.

The attractive Bridge 12 at the entrance to High Lane Wharf

It was designed as a direct link between Manchester and the Midlands, and following its Act of 1826 it was completed five years later. At twenty six miles long, it was one of the last narrow-gauges canals to be built. Designed by Thomas Telford, the dean of British civil engineering, although built by William Crossley, it employed much of the design and construction expertise developed over the previous seventy years. In order to make the route as straight and as economical as possible Telford used audacious ‘cut and fill’ techniques with high embankments, ambitious cuttings and eight aqueducts. All of its twelve locks are concentrated in a single flight at Bosley. Another distinguishing feature of the canal is the acute angle at which many of the bridges crossed the canal. Bridges were much more difficult to build at an angle but at this time, long after the period of ‘canal mania’, the engineers and masons had considerable experience of solving such problems. Building the bridges in this way saved the considerable cost of realigning the roads crossing them.

Abrasion grooves on Bridge 12

Abrasion grooves on Bridge 12

Its architecture too, was improved. The original profile for many canal bridges was semi-circular but these often caused problems for the horses, rubbing against the sides. Over time the bridge profile became more elliptical, even though they were more difficult to build, and the bridges on the ‘Macc’ show the culmination of this evolution.

The Macclesfield Canal opened on 9th November 1831, just over thirteen months after the Liverpool and Manchester Railway had its inaugural journey. It would seem to be a bad omen as the railways very soon proved their superiority, but for the first few years it was profitable and built up its commercial interests. It ran close to many coal mines in the Poynton area and it built seven wharves to serve its customers, including the one at Marple which is now being developed by the Canal and River Trust. However, this heyday did not last long. The rapid expansion of the railways was leading to intense competition, the cutting of freight rates and reduction in staff costs but to no avail. In 1846 the Macclesfield Canal and the Peak Forest Canal were taken over by the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway.

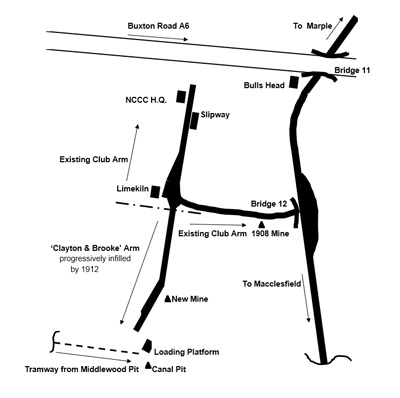

Even with new owners, the Macclesfield Canal still served the many coal mines in the Poynton area. The wharf is the only proper arm off the Macclesfield Canal - all the other wharves are on the main canal. It was originally dug with a short entrance ‘leg’ then a branch to the right followed soon afterwards by a branch to the left, each about a hundred and fifty yards long. The end result was a tee-shape, with the right hand arm handling general cargo whilst the left hand arm served Middlewood and Norbury pits.

This left-hand arm was operated by Clayton & Brooke, the coal company. It owned several coal mines in the area, most notably at Middlewood and at Norbury but it also owned three small pits which were actually adjacent to the wharf. Coal was loaded into tubs at the mines then ran on tram tracks directly to the quayside and into barges. It also received coal by water from the quayside at Middlecale Pit in special deck-loaded tubs. Much of the coal was delivered direct to canal side mills or to wharves in mill towns such as Macclesfield, Bollington and Marple. Distribution of coal by carter was by a firm named Potts and the horse-drawn carts were checked out via the weighbridge, situated at the entrance to the yard opposite Windlehurst Road. In its heyday between 1850 and 1875 there were about twenty pits in the Poynton area shipping coal through the wharf. The coal trade declined over the course of the nineteenth century with the vagaries of the cotton industry and competition from higher quality Yorkshire coal, The arm was still in existence in 1910 but as the mines in the vicinity closed down it was filled in with pit spoil by 1914. Traces of this arm can still be seen as a depression in the ground and small ponds. From time to time there have been discussions about excavating it once again but it always proved uneconomic. However, as an irrelevant point of interest, the woods surrounding this part of the wharf are the original ‘Middle Wood’.

Bridge 11 carrying the A6. Note the elliptical shape allowing more room for horses.

As well as the collieries at Middlewood and Norbury, Clayton & Brooke also had operated lime kilns and brick works as an integral part of their business. In the early days there was a small, two pot, limekiln between the two arms of the wharf but that proved to be unviable. It was mainly operating in the 1870s but by 1902 it had closed down. Its draw tunnel can still be found in the garden of a private house. The brickworks was at the end of the left hand arm, marked out by a tall chimney which can be seen in early photos. The brickworks closed in 1892 but their products can still be found in some properties in the district, mainly used as pavers.

Besides the coal traffic at the Arm, several general cargoes were handled by public carriers, such as Kenworthy & Co. and J. P. Stanwick & Co. Pickfords also used the wharf extensively as, although they were no longer based in Poynton, they had considerable business in the area. At their peak Pickfords owned around 400 canal boats, but withdrew from canal carrying to concentrate on road transport in 1845. One local cargo handled by Pickfords via the wharf was barrels of hats bound for London, from Christy’s factory in Hillgate, Stockport. Other goods made in Stockport were also shipped out via High Lane wharf as this was the nearest canal wharf to Stockport.

Warehouse and wharfinger’s house.

To facilitate this trade there was a crane for transferring cargo, a warehouse, similar to the one at Marple Wharf but without the boat dock and other general purpose equipment. The warehouse was substantial, measuring 53’ x 47’ and equipped with two loading bays. The wharfinger had a house alongside the warehouse and the yard was surrounded by a substantial wall for security, much of it still in evidence today. All goods both in and out had to pass through gates leading onto the Buxton turnpike (modern A6). At this point, next to a small cottage used as an office by the operator, there was a mechanical weighbridge. This was constructed mainly of wood and used a system of knife edges and levers connected to an external steelyard to allow operators to carry out the weighing function. The sophistication of using levers as a mechanism evolved over more than a century and their use continued until the latter half of the twentieth century. The use of steelyards to provide weight data was replaced by sophisticated dial systems connected to the lever system and weighbridge decks moved from wooden construction to steel.

As well as commercial activity, pleasure cr aft existed on the ‘Macc’ certainly before World War I and there were several boathouses on the opposite side to the towpath along the approach to the wharf back in 1900 when the work area was in commercial use. Boathouse rents in those days were half a guinea (52.5p) per annum, this being collected by the L.N.E.R., the canal owners since 1923 as successors to the Great Central Railway. It was also necessary to purchase a ‘privilege’ licence from the railway company to operate a pleasure boat on the Macclesfield Canal. This cost eight shillings.

aft existed on the ‘Macc’ certainly before World War I and there were several boathouses on the opposite side to the towpath along the approach to the wharf back in 1900 when the work area was in commercial use. Boathouse rents in those days were half a guinea (52.5p) per annum, this being collected by the L.N.E.R., the canal owners since 1923 as successors to the Great Central Railway. It was also necessary to purchase a ‘privilege’ licence from the railway company to operate a pleasure boat on the Macclesfield Canal. This cost eight shillings.

Thus the High Lane Arm of the Macclesfield Canal has been a base for pleasure cruising since World War I, but it was not until a few years before WW2 that the first moves were made for boaters in the area to form some form of association. The catalyst for this reaction was a move by the local Rating Officer to levy rates on boathouses in 1937. A meeting of boaters was held and legal advice sought. This action did not prevent the collection of rates then and ever since, but it did prevent a proposed 6-year back dating. More importantly, however, this association led ultimately to a more formal proposal to start a cruising club based in the Arm (which up to this time had been used free of charge) by renting part of it from the L.N.E.R. In this manner the North Cheshire Cruising Club was born. To regularise their position they approached the railway company. Rather to the boaters surprise, the LNER were not only happy to have a boat club in the wharf but it would like them to rent the whole site. The suggested price was one shilling per yard (5 pence) but they could not afford such a high rental so a more reasonable figure was negotiated.

The club has retained and improved the site ever since. It is particularly noted for the boat garages lining its banks in which NCCC members keep their boats. The first Clubhouse was the old weigh-house next to the weigh-bridge at the entrance to the yard. The weigh-bridge was broken up for scrap and much DIY renovation work carried out to make the place habitable. 1975 was the next milestone in the Club’s history when a longer lease was negotiated with British Waterways and the large stone warehouse on the quayside was acquired. With the aid of a grant from the Cheshire County Council and Loan Bonds from the members, the place was gutted and transformed into the present clubhouse. Although only a limited number of moorings and boathouses are available in the Arm to Club members, it offers a crane, slipway, hard standing, storage and workshop facilities (with showers, toilets and Elsan disposal) for all.

This is an important and historic local feature and facility. We must do all we can to conserve it and prevent the Canal and River Trust from “developing” it out of all recognition as they have done to Marple Wharf.

Words: Neil Mullineux

Photos: David Burridge

Last image '1956' shows excavating to the remains of the boat that brought coal from Baden’s Wharf, circa 1956.

Penultimate images features the towpath bridge (12) over the spur and shows the grooves worn by the tow ropes as the horse pulled the boats along the Maccelsfield Canal.