Broadoak Moated House

(Location: Open Street Map - Three Words - Grid Reference SJ 93945 87595)

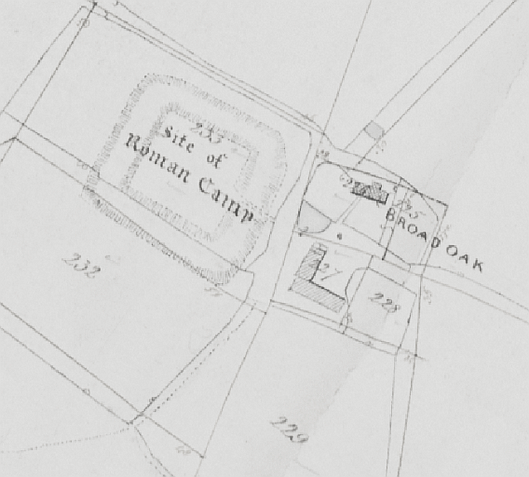

On the edge of Stockport Golf Club, next to Broadoak Farm, is a squarish platform of land, surrounded by a moat on all sides. Although it is private property and well away from any roads it is adjacent to a public footpath running from Torkington Road to the Middlewood Way. It is quite a sizeable feature in the landscape but what exactly is it? The usual description for anything old and of unknown origin is ‘Roman’ - Roman Bridge, Roman Lakes etc. and the tithe map of 1838 would seem to bear this out - ‘Site of Roman Camp’. Not only that but it lies close to one of the most likely routes for the Roman road between Stockport and Disley.

However, what records we have seem to point in another direction. In the medieval period this whole area was part of two royal forests - Macclesfield Forest and Peak Forest. The western boundary of Macclesfield Forest ran north from Congleton, passing through Gawsworth and Prestbury to Norbury. It then crossed the “stream at Bosden” by a bridge called ‘Salters Bridge’ on its way to cross the Goyt at Otterspool Bridge. The “stream at Bosden” is the present Ochreley Brook and Poise Brook and ‘Salter’s Bridge’ is probably where the A626 crosses Poise Brook. This would mean that Torkington was just inside the Macclesfield Forest but by the fourteenth century the application of Forest Laws were easing.

Tithe Map: Bishop of Canterbury, William Howley

Tithe Map: Bishop of Canterbury, William Howley  Modern Plan

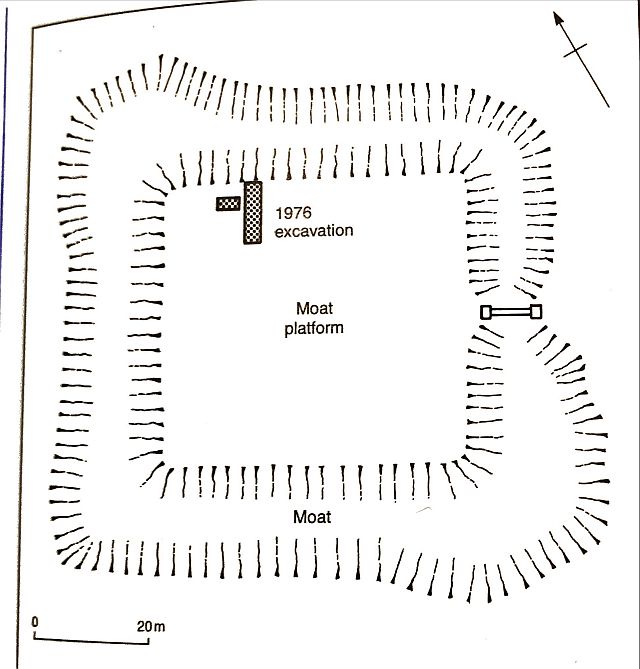

Modern Plan

In the mid-century, John de Legh (no relation to the Leghs of Lyme) cleared 60 acres of woodland in Torkington. This was a substantial single acreage but it was part of a wider trend at that time of piecemeal clearances of land within the Forest of Macclesfield. He built a manor house, surrounded by a moat, in about 1354. The house included ‘two chambers and a kitchen’, and outside the moat were a barn, stables and associated fields. The moat, as well as being a mark of prestige, also ensured a degree of protection in violent times. These moated sites were an expression of wealth and social prestige and they tend to fall into two cat-ergories. Some were the manor houses of the lesser gentry and are usually assumed to have been the primary settlement within a medieval manor. Secondly, and more commonly, were the moats that were the homes of wealthy freemen.

John’s early career involved violence, theft and murder, a not unusual background for minor landowners at that time. However, he was probably more successful than most as by a series of grants in the late 1340s and early 1350s he had become the largest landowner in Torkington. He already possessed a moated hall at Booths, near Knutsford and by 1354 he was the steward of the Duke of Lancaster’s lands in Cheshire. The Broadoak moated house was meant to put his stamp on this part of Cheshire, to show who really mattered.

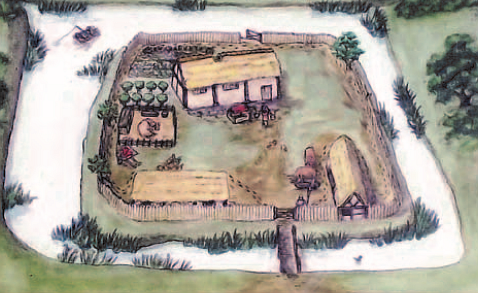

The first buildings would have been handsome by the standards of the time. There is no detailed evidence apart from the short description quoted above and a preliminary archaeological exploration in 1976 which found evidence of at least one fourteenth century building on the edge of the moat platform. The site is substantial, measuring about 53 by 47 metres surrounded by a moat approximately 15 metres wide. On two corners the moat has been widened to create what were in all probability, fish ponds. This site is comparable with the moated site at Timperley Old Hall on Altrincham golf course which has been thoroughly investigated over a period of thirty years by the South Trafford Archaeological Group in coordination with the Greater Manchester Archaeological Advisory Service. The Broadoak site is slightly larger than Timperley but the indications are that the buildings within the moated area would be similar. Both sites are on low-lying land covered in boulder clay which provided the moat with a natural impermeable lining.

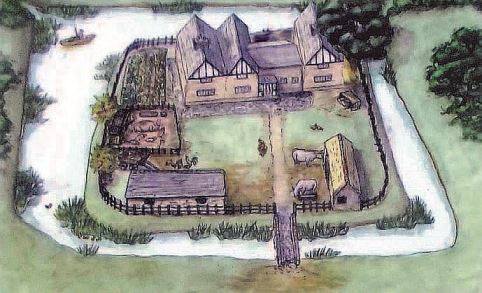

There are signs of occupancy at the Timperley site dating back to neolithic times but the earliest documentary evidence are some legal papers witnessed by Walter de Timperlie in the early thirteenth century. Over time it has passed through various owners including well-known families such as the Ardernes and the Breretons, but it was never a principal dwelling. There were three main building stages. A medieval hall was replaced by a 17th century hall made of brick and in the 19th century this brick-built hall was demolished and a garden established in its place.

This artist’s impression gives a good indication of what Timperley Hall would have looked like in the medieval period. The main house would have been a manor house surrounded with ancillary buildings to house cattle and for other farm purposes. The cattle would have grazed in fields outside the moat but there was provision to bring them into the enclosure if necessary as cattle rustling was not unknown. Many moated sites went into decline from the end of the fifteenth century and this house too was abandoned around the beginning of the 16th century.

Timperley Hall - Late medieval

Timperley Hall - Late medieval  Timperley Hall - 17th century

Timperley Hall - 17th century

Although there has only been limited excavation, it appears that a new building, Torkington Hall, was constructed on the Broadoak moated site during the early 17th century, replacing the medieval buildings. The Altrincham moated site went through a similar transition at about the same time so the artist’s impression of that site probably gives an idea of what Broadoak would have looked like at that time.

However, this first Torkington Hall was not to last long as a manor house. In the eighteenth century the Legh family re-established a residence in Torkington by building an ‘occasional dwelling’ known as Torkington Lodge. A fine Grade II listed Regency building, it was built in about 1782 by John Legh, but he did not live there for long. In 1811 it was advertised for lease as a ‘Genteel Residence on the great road to London.’ It passed through various hands and was a school for young ladies for a time. However, the industrialist Thomas Barlow and his son owned it until 1932 when it was sold to Hazel Grove and Bramhall UDC and since then it has been used for a variety of local government purposes.

Torkington Hall suffered in comparison with its fashionable neighbour and it gradually declined in status to that of a tenanted farm. Even for that purpose the site was not ideal because of the limited access. A defensive site was no longer needed so a new farm was built nearby, outside the moat. All surface traces of the habitation have long since disappeared.

There is still much to find out about the site and its history. It has been recognised by Historic England and designated as a scheduled monument since 1980. Limited excavation on the island has identified three phases of activity, all involving timber structures. In 1976 a small exploratory investigation was dug by students of the University of Manchester Extra Mural Department. The archive and finds were deposited with the Greater Manchester Archaeological Unit. Artefacts found included medieval pottery, 14th or 15th century roof tiles, and post-medieval clay pipes, pottery and nails. Within Greater Manchester there are 63 certain and 22 possible moated sites known of which five have been excavated. There is no question that the moat at Broadoak is by far the best preserved.

And that is where matters stand. We have a fascinating site of historic interest and nothing is being done about it. A group in Trafford were faced with the same situation forty years ago and they managed to build up enough interest to carry out their own excavations and then bring in further professional help with the aid of Heritage Lottery Funds. We already have a group with both knowledge and experience - Mellor Archaeological Trust. They have carried out two very successful projects at Shaw Cairn (neolithic) and Mellor Mill (Industrial Revolution.) Perhaps they could take on another.

Neil Mullineux, February 2021

Broadoak: Southern arm with fishpond in the foreground

Broadoak: Southern arm with fishpond in the foreground

Broadoak: Northern arm

Broadoak: Northern arm