Marple Liberal Club, opposite the Navigation Hotel

I often think it’s comical – Fal, lal, la!

How Nature always does contrive – Fal, lal, la!

That every boy and every gal

That’s born into the world alive

Is either a little Liberal

Or else a little Conservative!

Fal, lal, la!

So sang Private Willis at the opening of Iolanthe at the Savoy Theatre in 1882. The comic opera satirises many aspects of British government, law and society but, like most satires, it was based on actuality. Parliament had a strong two-party system with Liberals and Conservatives and politics was becoming much more part of everyday life.

This had not always been so. The British electoral system of the early 19th century was viewed as extremely unfair and in need of reform. In 1831, only 4,500 men could vote in parliamentary elections, out of a population of more than 2.6 million people. The First Reform Act of 1832 corrected many of the abuses and widened the electorate, but not by much. Only one in five men could vote and women were explicitly excluded.

Modest though the changes were, the Act proved that change was possible but among the working classes (as opposed to landowning classes) there were demands for more. As the century progressed these demands grew and resulted in a second Reform Act in 1867. This increased the electorate to 2.5 million men but it was still based around property qualifications; it still meant that all women and 60% of menwere not represented. The pressure continued and resulted in a third Reform Act in 1884 (and eventually, to complete the enfranchisement process, Reform Acts in 1918 and 1928 which widened the suffrage to all men and women on an equal basis.).

In the 1870s, long before universal suffrage was brought in, it was widely recognised that the process of widening the electorate was unstoppable and both political parties were considering ways to obtain the support of newly enfranchised people. Benjamin Disraeli died in 1881 and some of his more forward-looking colleagues began to discuss ways of enlisting this support, a talent he had demonstrated throughout his career. Lord Randolph Churchill and some like-minded colleagues decided to establish an organisation for people who broadly accepted Conservative principles. It took many ideas from the benefit societies that provided mutual aid to their members but which were also a social organisation for the growing ranks of the middle and upper working class. The Primrose League started in 1884, the same year of the third Reform Act. There were two classes of membership, Knights and Dames who paid half a crown and associate members who paid sixpence. Significantly the Primrose League was the first political organisation to give women the same status and responsibilities as men.

Disraeli is shown as the person responsible for bringing in the 1867 Reform Act, outpacing his rival, William Gladstone.The concept was phenomenally successful; within two years the Primrose League had a quarter of a million members and two million by 1910. This was a national organisation, organised centrally, but local communities took note and decided to emulate this. In fact some had already anticipated the Primrose League. In Marple, for example, a group of local worthies gathered at the Jolly Sailor to form the Marple Conservative Association. Amongst those present were John Isherwood of Marple Hall, J.Hudson of Brabyns Hall, Joel Wainwright and Jesse and Wright Tymm. In many ways, this group was typical of the Conservative party. No aristocrats (because there weren’t any in this locality) but landed gentry (Isherwood and Hudson). The other three represented the rising middle class - Joel Wainwright, a retired manager of Strines Printworks, and Jesse and Wright Tymm who owned the lime kilns and and soon took over the brickworks at Rose Hill.

Disraeli is shown as the person responsible for bringing in the 1867 Reform Act, outpacing his rival, William Gladstone.The concept was phenomenally successful; within two years the Primrose League had a quarter of a million members and two million by 1910. This was a national organisation, organised centrally, but local communities took note and decided to emulate this. In fact some had already anticipated the Primrose League. In Marple, for example, a group of local worthies gathered at the Jolly Sailor to form the Marple Conservative Association. Amongst those present were John Isherwood of Marple Hall, J.Hudson of Brabyns Hall, Joel Wainwright and Jesse and Wright Tymm. In many ways, this group was typical of the Conservative party. No aristocrats (because there weren’t any in this locality) but landed gentry (Isherwood and Hudson). The other three represented the rising middle class - Joel Wainwright, a retired manager of Strines Printworks, and Jesse and Wright Tymm who owned the lime kilns and and soon took over the brickworks at Rose Hill.

The group acted quickly and efficiently. A site for the Club was found on Church Lane where the old grammar school had been. This cost £200 and plans for a splendid new building were drawn up by Mr Hunt, a Stockport architect. It was described at the time, as being ‘“of ornamental character’. Richard Simpson won the contract for building the club with a price of £1200 and the foundation stones were laid in May 1880 by Mrs Bradshaw-Isherwood of Marple Hall and Miss Hudson of Brabyns Hall. By the time the building was finished it had cost £1500 and the next few years were devoted to paying off the loan. Although mill owners generally supported the Liberals because of their belief in free trade, a few supported conservative principles, possibly because their particular business was not export oriented. The Syddall family, owners of Chadkirk Printworks, were Conservative supporters and so too was James Shepley, owner of Rhode House Mill in Hawk Green. Indeed he would seem to have been a considerable benefactor as at a very early stage the building was named Shepley Hall.

The rooms for the use of members were all on the ground floor, 'commodious, lofty and well-ventilated and for winter they are fitted up with heating apparatus'. On the first floor was a large function room with a stage suitable for public meetings or entertainment. It had a fitted kitchen to provide the ‘culinary requirements of those visiting the establishment.’ The newspaper account expands on this by emphasising that many Conservatives wanted to join a club in a locality favoured by summer excursionists. The implication is that they were hoping to attract members from a much wider area than Marple but as we have no records of membership we cannot confirm if this came about. Certainly the committee members were essentially local business men. For the first few years the chairman was Thomas Johnson, a local solicitor in his late twenties. This was certainly a young age for such a key position but perhaps they wanted someone who would be an energetic fund raiser. In any case he had sound local roots as both he and his brother, another solicitor, were grandsons of Aaron Eccles, the solicitor and business adviser to Samuel Oldknow.

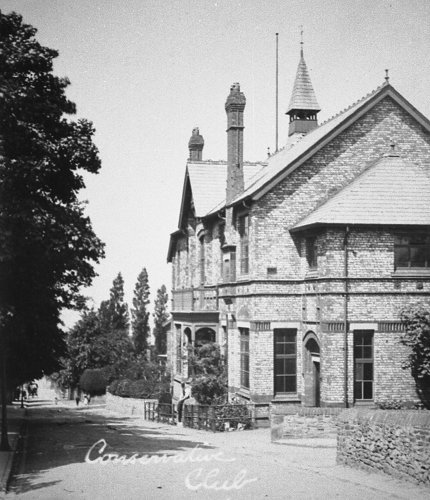

Marple Conservative Club, on Church Lane

The activities of the Marple Club, like its sister Clubs, were mainly social, giving members a congenial meeting place as well as regular social functions open to a wider public. They were involved in local politics as they formed part of the constituency association which chose and related to their MP or prospective candidate. The heyday of the organisation was mainly up to the First World War but throughout the Twenties and Thirties they maintained their role as an important social centre for community life but did not grow with the community. After the Second World War their influence began to decline and they were regarded as less relevant to the majority of the population.

The activities of the Marple Club, like its sister Clubs, were mainly social, giving members a congenial meeting place as well as regular social functions open to a wider public. They were involved in local politics as they formed part of the constituency association which chose and related to their MP or prospective candidate. The heyday of the organisation was mainly up to the First World War but throughout the Twenties and Thirties they maintained their role as an important social centre for community life but did not grow with the community. After the Second World War their influence began to decline and they were regarded as less relevant to the majority of the population.

There is an interesting report in the Stockport Advertiser in 1968 on the occasion of a ceremony to open an extension to Shepley Hall as it was called. Over the previous four years the Club had bought and razed adjacent cottages in order to create a car park and spent an additional £8,000 on refurbishing and redecorating the main building. At the same time they announced that, as an innovation, they would allow the admission of women as associate members. This is an appalling admission - almost a century after the club was founded they were finally admitting women but only on a second class basis. It just showed how out of touch they were, particularly as women had been central to all fund-raising activities throughout the history of the club. And what a contrast to the enterprising Tories who had established the Primrose League for both men and women on an equal basis in 1884, more than 80 years before.

The Liberals were always one step behind the Conservatives in trying to establish a mass movement, even though they were regarded as the party of reform. Nationally, the National Liberal Club opened in 1887, long after its Conservative equivalent, the Carlton Club. It was not affiliated in any way with the local Liberal Clubs and these did not form an association until 1907 whereas Conservative Clubs had an umbrella organisation which started in 1894.

It was a similar story with the local clubs. In Marple mill owners were the driving force behind the Liberal Association, Thomas Carver and Samuel Hodgkinson in particular as the owners of Hollins Mill. A Building Committee was formed in July 1887 and soon afterwards they formed a limited company to finance the building. Thomas Carver and Samuel Hodgkinson were directors and Walter Bright Hodgkinson, Samuel’s son, was the Secretary. The other directors were not in the same league, financially, but were solid members of the burgeoning middle class - a draper, a lace merchant, the owner of a small mill and a grocer.

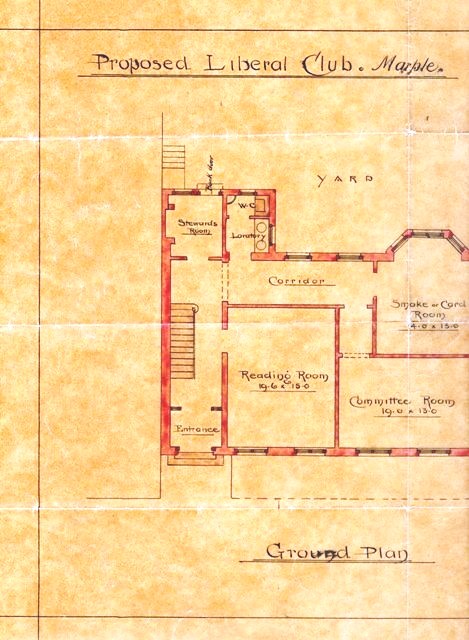

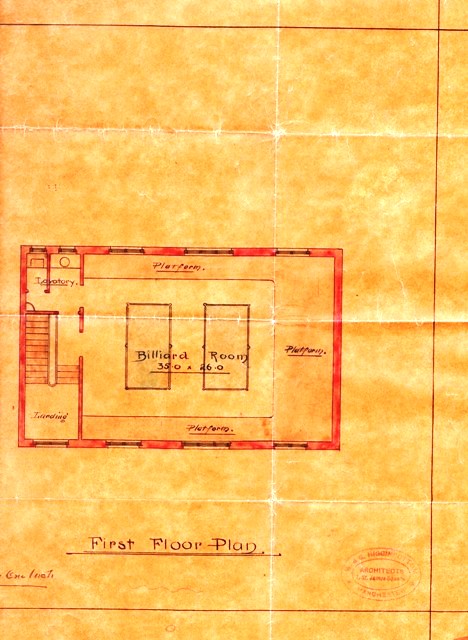

Proposed plan for Liberal Club, Marple on wax paper from Architects, H B Higginbottom of Manchester:

The prospectus was offering 1500 shares at £1.00 each as they had decided that £1500 would cover the cost of the building plus initial expenses. Thomas Carver had already agreed to provide a suitable plot next to Possett Bridge for both a Club and a bowling green at a very low rent of £5-12-0 per annum. Architects W&G Higginbottom were asked to draw up plans. The original estimate for the building was £735 but additional items and fees together with the cost of the bowling green (£48) brought the total to £1050. The bowling green had an excellent reputation for much of its existence and was the premier green in central Marple for many years until one was made in Memorial Park. The ground floor had a committee room, smoking and card room, and a reading room together with a services area for the steward. The first floor was devoted almost entirely to a billiard room with a raised platform running around three sides and space for two billiard tables in the well. The interior decoration was typically Victorian as described by the Hyde Reporter:

The entrance hall and staircase walls are painted two neutral greens, relieved by a maroon band stencilled on with a pale buff, and lines a stronger shade of the same colour. The ceilings are cream, the cornice being broken up in shades to correspond with the walls and the woodwork, the latter being in two shades of maroon, varnished. The library, and lavatory rooms are painted brown, relieved by a dado. The billiard room has been made to look cheerful and comfortable by the introduction of warm but quiet tints of colours. The ceiling is cream colour, the filling of the walls being a light tone of Pompeian Red, relieved by a chocolate dado, cream band and stencil of dark colour, the lines being black. The windows, cornice and woodwork in the room being modifications of colour which completely harmonise together.

All this was probably a little too sombre for our twenty-first century taste but the height of fashion in late Victorian Marple.

The fortunes of the Club seem to have followed a similar trajectory to the Conservative Club. A major social centre for the community until the First World War, then plateauing between the wars and a steady decline thereafter. As a registered members club it had more flexible opening hours than public houses and it took advantage of this to open during the afternoons when the pubs were shut. This attracted a new class of clientele, particularly building workers, from a much wider radius, who were all signed in as ‘guests’. The club would shut at six o’clock to prepare for their evening members and the afternoon customers would go over the road to the Navigation and other pubs to continue drinking.

Some professional ladies from Stockport and as far away as Manchester found out about the new attraction in Marple and often came to join the fun. They would arrange an assignation in the bar of the club then repair to a suitable venue such as behind the Navigation or the horse tunnel under Possett Bridge. A productive way to extend their working day. Rather than ladies of the night they were perhaps better described as ladies of the mid-afternoon. Unfortunately for this trade, the police also learned about the extended opening hours and raided the premises one afternoon finding numerous illicit ‘members’. All the committee members present, together with the steward were fined but it just made them more careful with their signing in procedures. Some time later there was another court case where the steward was accused of milking the gaming machines using a specially manufactured key. He was found guilty and fined but he kept his job as it was believed that one or two of the committee were also involved in the operation.

Marple Liberal Club Demolished in 1993

Marple Liberal Club Demolished in 1993

All good things must come to an end and for the Liberal Club it was 1988 when1 the Licensing Act of that year allowed public houses to open all day. This killed the Club’s afternoon trade almost immediately and the extension they had built to enlarge the concert room with a loan from the brewery was an added expense. Attempts were made to sell the building but there were no takers and the club closed for the last time in January 1993. It was sold for housing development and there is now no trace of the building that once played host to Lloyd George. No, there is one trace. The wooden sign on the outside of the building was salvaged and, after various travels in the district and to North Wales it is now on permanent loan to the Ring o’ Bells having been rescued by the Marple website.

Mark Whittaker, rescuer, with the Liberal Club Sign

Mark Whittaker, rescuer, with the Liberal Club Sign

So, these two venues, built in the 1880s, were important social centres for the town for over a hundred years. One has now gone completely but the other remains as a shadow of its former self. Will it find a new role in the community or will it be demolished to make way for something else? Much of our heritage has gone but it is not all worth keeping. We have to decide what do we want to pass on to the next generation.