Take a walk along Town Street, Marple Bridge, cross the end of Hollins Lane, pass the little pay and display car park, and below the bridge, at the beginning of Longhurst Lane, lies one of the oldest industrial buildings in the area, Spade Forge formally known as Forge Bank Mill. Its earliest record dates from 1776, but was probably operating before that. Although it has now been converted into a house, its past remains for all to see. The waterwheel which drove its machinery is still in situ, with the millpond dam, 40’ wide and 20’ high, sluice gate seating and head race adjacent.

The Spade Forge at Marple Bridge

This was a forge that made spades, pickaxes, plough shares and other tools for use all over the district, including for digging the Peak Forest Canal, between 1796 and 1804. It was powered by a waterwheel, turned by the fast-flowing Mill Brook which rises on the moors above the hamlet of Mill Brow, ¾ mile above Marple Bridge. This small stream powered at least five water mills, of various purposes, along its banks at one time or another. Spade Forge was the lowest down, being just above Mill Brook’s joining with the River Goyt.

The mill building was 35 feet long by 16 feet wide, and the main waterwheel was mounted at the middle of the long side. It was high breast shot**, 15 feet in diameter and 4 feet wide with 40 buckets or so. The wheel axle pierced the wall of the building, connecting to a 4 foot diameter cast iron trip wheel which drove a tilt hammer. There were square holes around the circumference of the trip wheel into which cams could be inserted to vary the frequency of hammer blows needed to shape different tools. At some time in the 19th Century, a smaller cast iron wheel, 9 foot in diameter and 1 foot wide, also high breast shot, was installed in front of the main wheel, supplied with water via a cast iron pipe connected to the centre of the sluice gate. This wheel drove the forge bellows, a drilling machine and a grindstone. Water from both wheels left the wheel pit through a culvert running under the mill yard and the road and back into the stream via an opening at the bottom of the retaining wall of the track from Longhurst Lane to Low Lea Road, which can still be seen.

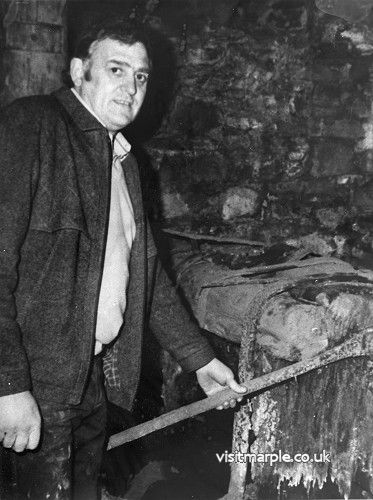

The forge was owned by Thomas Lees of the Townscliffe Estate and was operated by many generations of the Yarwoods as his tenants. The first record of work is a bill dated 1776, for 3/6d, for lengthening two mill spindles for ‘Ludworth Corn Mill’ by James Yerad (Yarwood). The Yarwoods continued to work the forge until competition from mass production forced them out of business in 1920. It could possibly have been closed for a period between 1827 and 1845 when there were several ‘to let’ or ‘for sale’ notices for the forge in the Stockport Advertiser and suggestions of a possible change of use to bleaching. This does not seem to have happened, and by the time of the 1851 census the Yarwoods are listed as spade makers once again. Other branches of the family were associated with the business. In 1804 there was a Richard Yarwood, Spade Maker and Dealer, with premises in Churchgate, Stockport, and in 1873 there  Inside Spade Forge before restoration in the late 1990swas an advertisement in the Stockport Advertiser for ‘Yarwood's celebrated spades, shovels and draining tools, cart arms etc.’ from James Yarwood, Iron and Steel Merchant trading in Heaton Lane, Stockport, and it seems likely that these people were members of the same family. In the early 20th Century spades made at the forge were sold in the local ironmongers run by Miss Alice Yarwood, sister of John Yarwood, the last operator of the forge. This shop was located where Ian Mann’s undertakers is now.

Inside Spade Forge before restoration in the late 1990swas an advertisement in the Stockport Advertiser for ‘Yarwood's celebrated spades, shovels and draining tools, cart arms etc.’ from James Yarwood, Iron and Steel Merchant trading in Heaton Lane, Stockport, and it seems likely that these people were members of the same family. In the early 20th Century spades made at the forge were sold in the local ironmongers run by Miss Alice Yarwood, sister of John Yarwood, the last operator of the forge. This shop was located where Ian Mann’s undertakers is now.

Thomas Lees died in 1884 and the forge was bought by William Jowett, of the Manor House, Mellor. In 1921 a James Ardern rented the premises from the Jowetts. He turned the forge into a sawmill and timber merchants, and two years later a joiner called George Buxcey became part of the business. The large waterwheel was used to drive a circular saw. In 1928 a dynamo was connected to the small wheel to provide electric light for the forge, five years before electricity arrived in the rest of Marple Bridge! When that happened, the small wheel became redundant, being dismantled and sold as scrap. By 1947 George Buxcey had bought the premises from the Jowetts, making this the first time that it was worked by the owner. He continued to operate as a joiner and builder until his death, and sometimes used the large waterwheel to operate the machinery. As a child in the 1950s the author remembers standing on the bridge watching with fascination as the wheel rumbled round. Many readers will recall George Buxcey’s other local business interest when from 1941 to 1961 he was the landlord of the Railway Hotel on Town Street, renamed the Royal Scot in the 1970s.

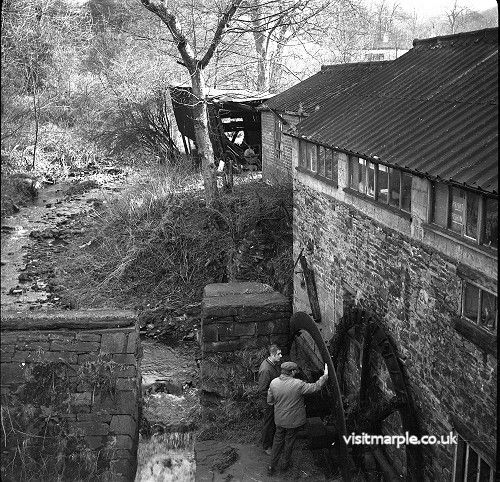

To allow efficient timber working, alterations were needed to the building. The roof was raised about three feet, and the Derbyshire gritstone roof flags replaced by corrugated asbestos cement. Windows were put in the top part of the building and the floor levelled to create a joiners work room. This 1973 photo shows the derelict wheel silted up and the edge of the corrugated asbestos roof. After the departure of George Buxcey the premises were used by a succession of builders, but by the 1980s were in a state of disrepair.

Frank CurtisIn 1981 local builder Frank Curtis and his wife Jean started to restore the complex. Over the next few years they worked tirelessly to clear out silt and debris which buried a third of the waterwheel, the tail race culvert, and the basement of the building. They restored the seatings of the sluice gate, removed weeds and saplings from the dam and reinstated the joinery workshop. In front of the workshop was a concrete platform which turned out to be the roof of a brick air raid shelter. This image looking towards the wheel and mill dam shows the concrete roof of the air raid shelter in the foreground. This covered the original steps leading down to the waterwheel area, so the only access was by ladder. Movement about the site became a lot easier after it was removed in the spring of 1982 and the steps reinstated. Fronting on to Longhurst Lane was a rickety wooden garage and a small wooden cabin which had been a butcher's shop, Mr Shallcross’ cobblers and an antique shop over the years, photo. The garage collapsed during a gale in January 1984, the shed being dismantled the following month. With help from the Manpower Services Commission, 700 tons of silt were removed from the wheelpit, culvert and mill pond, and the banks of the mill pond lined with stone to prevent further silt washing down from the slopes above.

Frank CurtisIn 1981 local builder Frank Curtis and his wife Jean started to restore the complex. Over the next few years they worked tirelessly to clear out silt and debris which buried a third of the waterwheel, the tail race culvert, and the basement of the building. They restored the seatings of the sluice gate, removed weeds and saplings from the dam and reinstated the joinery workshop. In front of the workshop was a concrete platform which turned out to be the roof of a brick air raid shelter. This image looking towards the wheel and mill dam shows the concrete roof of the air raid shelter in the foreground. This covered the original steps leading down to the waterwheel area, so the only access was by ladder. Movement about the site became a lot easier after it was removed in the spring of 1982 and the steps reinstated. Fronting on to Longhurst Lane was a rickety wooden garage and a small wooden cabin which had been a butcher's shop, Mr Shallcross’ cobblers and an antique shop over the years, photo. The garage collapsed during a gale in January 1984, the shed being dismantled the following month. With help from the Manpower Services Commission, 700 tons of silt were removed from the wheelpit, culvert and mill pond, and the banks of the mill pond lined with stone to prevent further silt washing down from the slopes above.

Central to the project was restoration of the main wheel, an expensive operation. To raise funds they asked local people to sponsor parts of the wheel, such as axle, spokes, paddles and buckets, winding mechanism and sluice gates. This added up to 102 components as well as 672 nuts, bolts and washers to fix everything. There was no shortage of sponsors, and for each one a named brass plaque was attached to their component. Assembly of the wheel was completed by February 1986. Three photographs (a, b, & c) show plaques on various bits of the wheel.

After removing sludge and layers of cinders, bricks and flagstones from the basement, the original floor proved to be a rock shelf. Here they found the blacksmith’s anvil, amongst iron and bolts on the floor, was a shape which could have been used to mould metal shovels, as well as a branding iron used to stamp the trade mark on the shovels. These investigations showed that the tilt hammer had a shaft 6’ long, and also revealed the sluice gate mechanism which the smith would have used to regulate the speed of the waterwheel for operating his various tools.

The workshop had long lines of windows fitted to transmit maximum light and the traditional Derbyshire stone roof was reinstated. Restored building, as in 1992. The aim was to use the building as a craft centre with a small museum so the public could see how the waterwheel had operated the forging machinery. The venture was opened by the Mayor of Stockport on 2 September 1987 and a great crowd turned out to watch the wheel turn for the first time in nearly 50 years.

The building attracted a lot of attention from members of the public for a while. As well as visiting the craft shop, you could go into the room behind the waterwheel to see the remains of the tilt hammer and other machinery. Unfortunately interest waned and by the mid 1990s there were not enough visitors to cover the necessary expenses, so Mr Curtis closed it down, and it has now been converted into a house. The waterwheel is still there, complete with brass plaques in memory of the sponsors. Although no longer operational, it shows very well the features of a small water powered factory, and you can go and look at it any time you like as you walk from Town Street to Longhurst Lane. .

**There are several different designs of waterwheel, depending on what level the water hits the wheel. If the wheel is overshot, water falls on the top, but if high breast shot the water falls below the apex of the wheel so a bigger wheel can be used for the same water flow, giving more torque or turning power. This photo shows high breast shot wheel and headrace below apex of wheel.

Judith Wilshaw - January 2021

Photos: Peter Corcoran, Jean Curtis, Judith Wilshaw and the Virtual Tour

References: Forge Bank Waterwheel by Jean Curtis. c.1987. Historic Industries of Marple and Mellor Second edition 1989.

The site on Boxing Day 2020