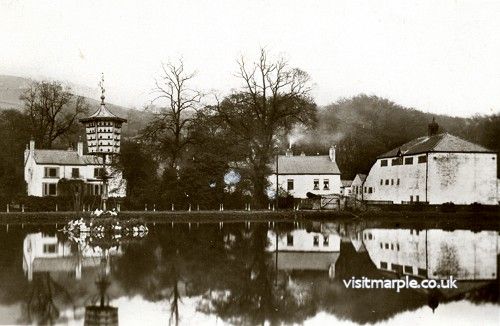

Anyone travelling to Strines station will pass an exotic structure on the left hand side - a dovecote planted firmly in the middle of the mill pond. It is a Grade II listed building but that immediately raises two questions. Why is it there and when was it constructed? The short answer to both these questions is the same - “We don’t know” but we can make some informed guesses.

The Strines Dovecote

First, the date. English Heritage claim it is of uncertain date but probably late C19. However, according to Rosemary Taylor, the Strines historian, it was there in 1852 because it appeared on the cover of the Strines Journal of that date. The printing works was first established in 1792 but experienced two subsequent expansions. The reservoir where the pigeon cote was erected was excavated about 1832 so that would seem to date the pigeon cote to between 1832 and 1852. So far we cannot be more precise.

Which leads us on to the second question - “Why was it erected?” Pigeon cotes or dove cotes go back a long way. The Romans may have been the first to introduce dovecotes to Britain but the birds were not commonly kept until after the Norman invasion. In medieval England the possession of a dovecote was a symbol; of status and of power and was consequently regulated by law. These dovecotes were usually purpose-built buildings but the law was relaxed after about 1600 so many later farms had dovecotes until their use declined after the 18th century. Doves and pigeons were a valuable source of meat, manure and feathers for mattresses.

Although they may appear picturesque to modern eyes, dovecotes were functional buildings built in vernacular style using local materials. The main function of a dovecote was to supply the household with a luxurious food - the tender meat of young pigeons. A pair of dovecote pigeons produced a clutch of two eggs, which they incubated for seventeen days. Then the young were fed by both parents with regurgitated liquid food (‘pigeons’ milk‘), and they grew rapidly. By the age of four weeks they were ready to fly. In nature the parent birds would then drive them from the nest. In domestication the pigeon-keeper ‘searched’ the dovecote for ‘squabs‘, the young birds which were almost fully developed, and wrung their necks. At that stage they were almost as large as the parent birds but their flying muscles had never been used; consequently their meat was very tender, and was much prized as a delicacy. Pigeon meat was NOT available throughout the year, contrary to the much-stated belief. The f irst squabs of the year were hatched early in March, and would have been ready for eating 3 - 4 weeks later if Lent had not intervened.

irst squabs of the year were hatched early in March, and would have been ready for eating 3 - 4 weeks later if Lent had not intervened.

Dovecotes ceased to be a matter of pride, and became socially unacceptable. Many were demolished; others were allowed to fall derelict. Outside the regions devoted to pastoral farming, few dovecotes survived the Napoleonic Wars without a change in use; but in some places they continued in use much longer. After the wars there was a partial revival, but it did not last. By the middle of the nineteenth century other developments in farming, and changes in the law, had effectively put an end to dovecotes. So, historically, it would seem that the Strines dovecote is very much an outlier, built long after dovecotes had a role in society. We can only assume that it was built for pleasure and enjoyment rather than as a source of food. By the 1830s or 1840s the Industrial Revolution was well under way and the logistics of getting food from rural to urban environments was well developed. There was no need for squabs though that is not to say that the occasional one would not be welcomed in much the same way as a rabbit for the pot.

However, this was not an entrepreneurial venture by an enterprising workman at the Print Works. The dovecote was in a prominent position and it would certainly have been given the blessing of the manager of the printworks, if not his wholehearted co-operation.

So, how has it survived until now? The short answer is “It hasn’t.” It has been repaired several times in its history. It was originally made of yellow pine and copper nails which was why it lasted so long. The hexagonal shaped construction is topped by a pagoda-shaped roof sheathed in lead and surmounted with a heavy copper weathervane in the shape of a sailing ship. There is an engraved pattern on the copper and it would appear to have been made from a block printing plate.

There was a major repair in 1975 when three employees of the printworks took it upon themselves to renovate the cote, using an inflatable dinghy to access it over a period of four weeks. However, by the millennium it was in a sorry state once again, listing at a steep angle, the wooden walls virtually rotted away and very insecure on its foundations. In 2007 Melvyn Smith led a full scale restoration and they decided to do the job properly using a long-reach crane which certainly saved them from getting their feet wet. On inspection, when the structure was craned off, it was beyond repair and an exact replica was made from more durable European oak. The structure is six-sided with 12 nesting boxes in each face - 72 in total. The inside is quite complicated, each hole having its own nesting box. These are now easy to clean out. As much of the original as possible has been preserved so the weather vane, part of the roof and the iron support are all original.

But what about the occupants? Two pigeons were in residence when restoration started but these abandoned their home when it craned off. Sadly only crows and jackdaws are now in residence

The Strines Community have contacted a dove expert who thinks it would be very difficult to reintroduce doves to their former home. Still, there are 72 cosy roosts waiting for them if they can be tempted back.

The Strines History Group have mounted an excellent record of the printworks and its history in one of the original buildings near the dovecote. It is open most weekends during daylight hours and provides a fascinating glimpse of the printworks and the Strines community.

Strines Dovecote (search Pigeon Cote on the Virtual History Tour)

Words by Neil Mullinuex

Photos by David Burridge and Melvyn Smith

Further reading: Strines Journal Online (link not working)

Location: Grid Ref. SJ 96099 87999 (to check - link was wrong)