High Lane is the most southerly part of the township of Marple, and its very name tells us precisely why it developed. It straddles the A6, one of the busiest main roads in the country, but the route has been busy for a very long time, for it was part of the Roman main road from London to Carlisle, our local section running from Aquae Arnemetiae (Buxton) to ‘Mamucium’, with a fort in modern day Castlefield.

21st Century Traffic (A6 - Windlehurst Road Junction)

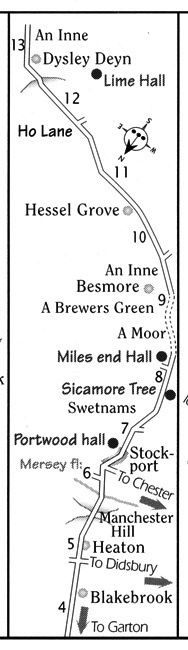

John Ogilby strip mapThe Romans were crack road engineers. They built so well that even after they withdrew from Britannia in the AD400s, their roads lasted with very little maintenance for the next several hundred years. We need to remember that the population was small by today’s standards and that most people tended to move around on foot, so that wear and tear would consequently be quite low. Even so, things were going downhill by medieval times because road maintenance depended on goodwill and voluntary efforts of local people. This was formalised by the passing of an Act of Parliament in 1555 requiring all able bodied in a parish to give 4 days free labour annually to repair the roads. This was so (in)effective that a few years later in 1563 the period of ‘Statute Labour’ had to be increased to 6 days! Its effects were variable: some parishes had few roads and didn’t have to make much effort, while others were crisscrossed by such a network that there were just not enough people to do the work.

John Ogilby strip mapThe Romans were crack road engineers. They built so well that even after they withdrew from Britannia in the AD400s, their roads lasted with very little maintenance for the next several hundred years. We need to remember that the population was small by today’s standards and that most people tended to move around on foot, so that wear and tear would consequently be quite low. Even so, things were going downhill by medieval times because road maintenance depended on goodwill and voluntary efforts of local people. This was formalised by the passing of an Act of Parliament in 1555 requiring all able bodied in a parish to give 4 days free labour annually to repair the roads. This was so (in)effective that a few years later in 1563 the period of ‘Statute Labour’ had to be increased to 6 days! Its effects were variable: some parishes had few roads and didn’t have to make much effort, while others were crisscrossed by such a network that there were just not enough people to do the work.

As time went on the population increased, meaning more movement of people and goods with predictable effect on the roads. Charles II looked at the problem, and decided that it would be a good starting point to know just where all the roads were. He engaged a ‘Royal Map Maker’, one John Ogilby, and sent him out in 1675 to map all the main roads in England. Ogilby produced a wonderful series of strip maps, showing buildings, features, landmarks and mileages along the way. You will be able easily to pick out places familiar today on the strip running from the Heatons area of Stockport through High (Ho) Lane to Disley. Interesting though this is, whether it led to improved roads is not clearly recorded.

Parliament tried out various ideas to formalise improvement and repair of the roads, without much real success. And then at the beginning of 18th Century the idea of The Turnpike Trust was mooted. Landowners and other wealthy people were invited to invest money to bring roads up to a good standard, then charge travellers to use them, with the income generated used to maintain the road and pay a dividend to investors. Toll bars, or gates were placed at intervals along the road, usually about every 3 miles, and a cottage provided for the toll collector. Toll houses have very characteristic architecture: a protruding bay with windows each side and a door in the middle, giving a view both ways along the road, so the collector missed no vehicles and could nip out the door sharpish to collect the money. With the march of development, many toll houses have disappeared, but place names still tell us of times past. We have ‘Hague Bar’ on the way from Strines to New Mills, and a house called ‘Fisher Bar’ where the road from Thornsett joins the road from Low Leighton in New Mills to Hayfield. The term Turnpike comes from the idea of a military road block, where soldiers stood at either side of a road and ‘turned their pikestaffs’ to bar the way of those passing. Toll gates often had spikes (pikes) along the top as a reference to the origin of the name.

Early turnpike roads were adapted from ancient tracks, but as usage increased and generated greater revenue from tolls, modifications and improvements could be made, or even a completely new section of road engineered. The original ‘High Lane’, which was turnpiked in 1725, followed the Roman road up Carr Brow, along Jacksons Edge Road, descending steeply to cross the route of the present A6 near the Rams Head before climbing equally steeply up the dead straight Disley Old (Roman) Road, across high moorland, and down into Whaley Bridge. A lot of wheeled traffic found this route a real struggle, and in the early 19th century a diversion was made round the bottom of the hill, giving us the route of the A6 we know today. What clues are there to this? Well, look at the houses as you pass along the road (preferably while someone else is driving!) You will not find any of a style before the early 19th century.

Turnpike roads often had mile posts. The idea was kept going by early Highway Authorities. This one is at the end of Middlewood Road in High Lane.Better roads led to increased usage and improved vehicles developed to carry goods and people, propelled by the power source of the time, the horse. Competition for business led to ever faster journeys, but it could still take several days to travel the length of the country, so inns would provide accommodation. Some kept stables of horses, and a coach could call in and quickly change horses to allow a continuous journey done in ‘stages’ between coaching inns, hence by stage coach. We still keep this term with ‘fare stages’ on bus routes today.

Turnpike roads often had mile posts. The idea was kept going by early Highway Authorities. This one is at the end of Middlewood Road in High Lane.Better roads led to increased usage and improved vehicles developed to carry goods and people, propelled by the power source of the time, the horse. Competition for business led to ever faster journeys, but it could still take several days to travel the length of the country, so inns would provide accommodation. Some kept stables of horses, and a coach could call in and quickly change horses to allow a continuous journey done in ‘stages’ between coaching inns, hence by stage coach. We still keep this term with ‘fare stages’ on bus routes today.

The turnpike system remained in operation until well on in the 19th century, but revenue from tolls was not adequate for good maintenance and improvement, and people got fed up with having to pay toll, so it was gradually phased out, and the responsibilities passed on to Highway Authorities, one of the earliest parts of local government.

So what can we see in the High Lane of today that speaks of the influence of the road? There was a toll house at the bottom of Carr Brow, known as the ‘Round House’, but long since demolished, and there would have been toll bars near the Rising Sun in Hazel Grove, and in Disley near the Rams Head. There are still quite a lot of pubs (inns) in High Lane, most of considerable antiquity. They serviced travellers as well as local people. The names are interesting. The Horseshoe dates from 1780. Did they run an associated smithy to keep travellers’ horses in order? A cattle market was held at the Red Lion, which dates from 1762, and you can just picture the cows being driven along the road to market. The Bulls Head (Red Bull in 1763) reflects the agricultural nature of the area. On the way to Hazel Grove is The Royal Oak, opposite Norbury Hollow Road, which led to Norbury coal pit, recognised today by the Clock House which was its pumping engine house. Norbury Colliery profited from use of the turnpike road to take their coal to the market in Stockport: the tolls were cheaper than Poynton Colliery had to pay on their route to Stockport.

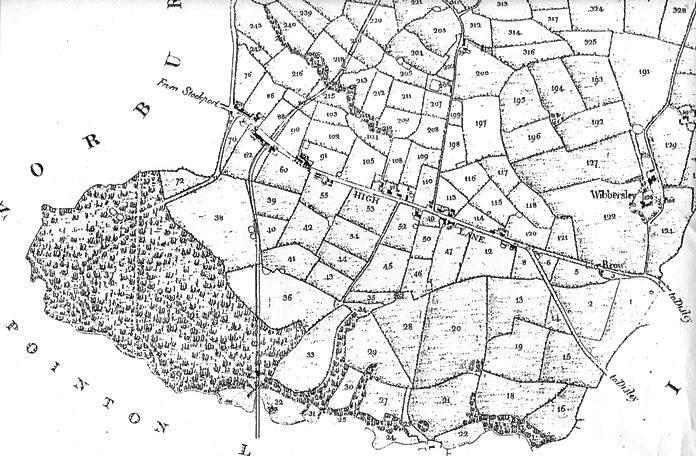

High Lane part of the 1825 tithe map

Early buildings were scattered along the road and you can pick out the location of one or two typical stone-built hill farmsteads like. The countrified nature of the area and convenience of the road encouraged the well-to-do to build country residences. None of these remain and the land has been redeveloped for other purposes in more recent times. But the presence in the community of well-heeled philanthropists was much to its benefit. A school was established in 1846 on land donated by the Leghs of Lyme, with building costs covered by public subscription, while the church followed in 1850, on land given, and a substantial amount of the building costs covered, by one Thomas Orford, a local landowner and philanthropist who lived next door at the eponymous Orford House. This was long since demolished and High lane Library now stands on the site, but the outbuildings remain as the Coach House Garage.

Picture of old Co-op, now an 8 til late Spar shop

Infill with more modest shops and houses accelerated as the population increased in the later part of the 19th Century, and has continued to modern times, really growing apace after WWII, when there were extensive developments on both sides of Andrew Lane, and around Alderdale Drive, opposite the church. The road gets busier by the day, exacerbated recently by the effects of the very new A555 relief road.

The 2000 year life of this road looks destined to run and run.

Text: Judith Wilshaw, February 2020

Photos: David Burridge & Judith Wilshaw