October 1859 – letter from William Foster, ship’s carpenter to his wife:

“My dear wife, I am sorry to inform you that the ship is a complete wreck. She has gone to pieces this morning, about 5 o’clock. There are only 25 – 30 of us saved out of about 400 souls.

Dear wife, give my love to the children and tell them I will be home as soon as the letter.”

The Royal Charter

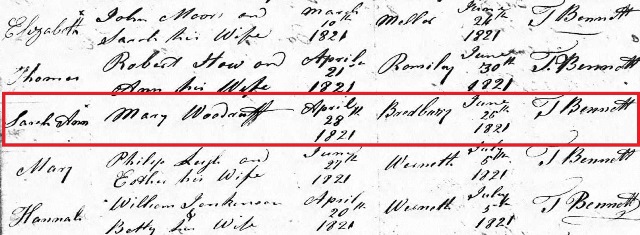

Amongst the passengers who did not survive was Sarah Ann Foster (neé Woodruff). Sarah was born in Hatherlow in the township of Bredbury on the 28th April 1821 and christened at Hatherlow Independent church. Her mother was Mary Woodruff and it is likely that Sarah was illegitimate, as her father’s name is not recorded.

We next hear of Mary Woodruff from an entry in Pigot’s Trade Directory for 1834 “Taverns & Public Houses - Hare & Hounds - Mary Woodruff, Chadkirk”.

Woodruff was a common name in the local area (Woodruff is the name of a creeping plant with a small white starry flower, which grows in woods and shaded hedgerows). The burial records for All Saints Church, Marple list many Woodruffs, in particular, there is a grave inscription for a family from Bredbury that includes a Mary Woodruff whose dates tie in with those of Sarah’s mother.

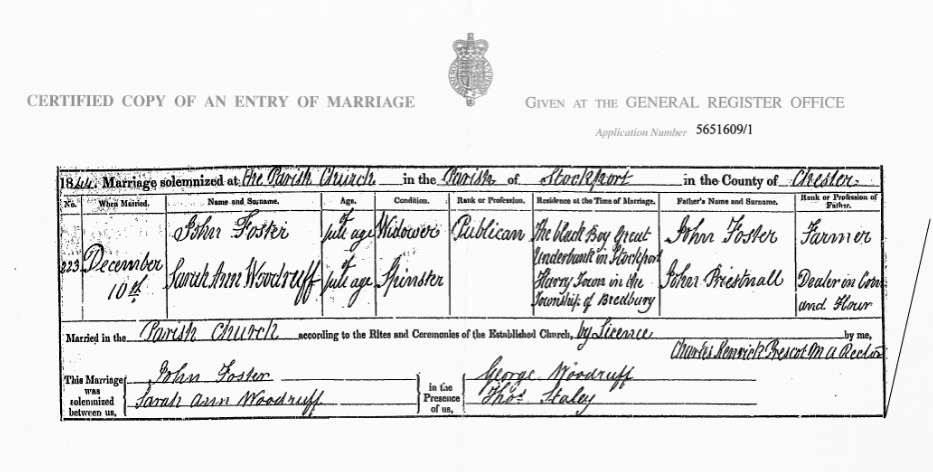

Sarah married John Foster, a widower, on the 10th December 1844 at Stockport Parish Church in the Market Place. John was the publican at The Black Boy, Great Underbank in Stockport. Interestingly, although Sarah’s father isn’t named on the baptism record, nor is he married to her mother, he is named on Sarah’s marriage certificate - John Priestnall, Dealer in corn and flour.

In the 1851 census, John and Sarah are shown as living at 2 Hall Street, Stockport. The census records John’s occupation as Spirit Merchant and records a daughter Sarah Anne aged 9 – perhaps a child from John’s first marriage. Also there are his mother-in-law Mary Woodruff, occupation publican, and two house servants. During their marriage, John spent time in Australia, establishing two hotels. While he was away Sarah ran their public house, the Shakespeare Hotel on Fountain Street in Manchester. The move to Australia was because of the business opportunities presented by the second phase of the Australian Gold Rush. Ballaratt, about 65 miles (110 kms) from Melbourne was ‘the world’s richest goldfield where a pick might yet strike a 2,000oz nugget.” After four years, John returned to Stockport leaving the hotels under the management of two Woodruff relatives.

When it was decided to sell one of the hotels, Sarah travelled alone to Australia to handle the sale. On the 26th May 1859 The Royal Charter left Liverpool, bound for Port Philip, Melbourne, Australia.

When it was decided to sell one of the hotels, Sarah travelled alone to Australia to handle the sale. On the 26th May 1859 The Royal Charter left Liverpool, bound for Port Philip, Melbourne, Australia.

The Royal Charter was a new type of ship – a steam clipper. The same shape and size as the famous tea clippers it was made of iron and fitted with auxiliary steam engines to supplement the sails and assist mobility. It had been built for Messrs Gibbs Bright and Co, shipping agents, on behalf of the Liverpool & Australia Navigation Company. The vessel was constructed at the Sandicroft Works on the Dee near Queensferry, Flintshire and launched four years earlier on the 31st July 1855. “Precisely at 1pm the great vessel moved in its place and the wine bottle, which consecrated its christening was flung by Mrs S Bright who performed the ceremony.” She was a fast ship used to carry passengers on the Australia run and could complete the voyage in as little as 60 days.

Sarah’s business was completed quickly and she boarded the Royal Charter on its return journey, setting sail from Port Philip, the port of Melbourne, on the 26th August 1859.

Sarah’s business was completed quickly and she boarded the Royal Charter on its return journey, setting sail from Port Philip, the port of Melbourne, on the 26th August 1859.

Sarah travelled Saloon class (first) with a Mrs Woodruff …probably the wife of one of her relatives. The official cargo of gold was worth over £350,000 but the gold carried by individual passengers would have more than doubled that amount. In total it was probably worth over £80m in today’s money. Sarah was supposedly carrying between £4,000 and £5,000 in gold (£450,000 to £570,000 in 2015).

On the 24th October 1859 The Royal Charter reached the south coast of Ireland and docked at Queenstown (Cobh) from where Sarah wrote to her husband to let him know the ship would shortly arrive in Liverpool. By 4.30pm the next day the ship was in sight of Holyhead harbour, Anglesey but the weather was deteriorating and by 10 o’clock that night there was a full gale. At 11 o’clock the Captain ordered the anchors to be lowered in the hope that the ship could ride out the storm. Suddenly, the anchor chains snapped and the Royal Charter was being driven towards Moelfre on the east coast of the island. The ship ran aground at 3 o’clock in the morning and at daylight it could be seen that the ship was only about 50 yards from the shoreline but facing a sheer cliff face. As word spread, the villagers from Moelfre gathered on the cliffs (below) unable to do anything but watch the disaster unfold. The ship was repeatedly battered against the rocks with such force that she broke into two pieces. Many passengers perished as they were hurled against the rocks. Others tried to swim to shore but were weighed down by the gold in their pockets and drowned. Maltese born crew member, Guzi Ruggier also known as Joseph Rodgers, tied a rope around his waist and managed to swim ashore. He secured the rope and helped the rescue of the 39 survivors – all men.

Reports of the shipwreck appeared in many newspapers across the UK and Australia. The Stockport Advertiser reported “the coast and the fields above the cliffs were strewn with fragments of the cargo and of the bedding and clothing – worse still, the rocks were covered with the corpses of men and women frightfully mutilated.” The Morning Chronicle reported: “the shore and the rocks were strewn with sovereigns which the passengers had vainly attempted to save with themselves”.

Bodies continued to wash up on the beach over the weeks following the shipwreck. Many of the bodies were buried nearby at St Gallgo’s Church, Llanallgo.

Charles Dickens visited the site soon afterwards and interviewed local people for a series of sketches, which were published as “The Uncommercial Traveller”, a collection of literary sketches and reminiscences. He gave a vivid illustration of the force of the gale:

“so tremendous had the force of the sea been when it broke the ship, that it had beaten one great ingot of gold, deep into a strong and heavy piece of her solid iron-work: in which also several loose sovereigns that the ingot had swept in before it, had been found, as firmly embedded as though the iron had been liquid when they were forced there.”

John Foster made his way to Moelfre but Sarah’s body was not recovered. After four weeks and three days, her body washed ashore at Portoferry, Co Down and was brought back to Stockport.

All Saints' Church

The funeral procession began from the Market Place, moved down London Road to the Nelson Inn, down Edward Street and across Waterloo Road; up Churchgate, along Turncroft Lane, New Zealand Road on to Bredbury Road, through Chadkirk and Dan Bank to Marple. Sarah was buried in the graveyard at All Saints on the 7th December 1859 aged 38.

"Sarah Ann, wife of the above, who was lost in the Royal Charter October 26th 1859 aged 38 years."John married for the third time to Martha Shaw at All Saints Church, Mobberley on the 21st January 1861. Sadly she died on the 20th May 1864 three days before her infant daughter Martha. John married for the fourth time to Ann who outlived her husband, dying in 1909.

"Sarah Ann, wife of the above, who was lost in the Royal Charter October 26th 1859 aged 38 years."John married for the third time to Martha Shaw at All Saints Church, Mobberley on the 21st January 1861. Sadly she died on the 20th May 1864 three days before her infant daughter Martha. John married for the fourth time to Ann who outlived her husband, dying in 1909.

John was a brewer, living at the Polygon, Ardwick (a street near the Apollo theatre) when he died on the 19th April 1887. Probate was granted on the 24th May and his personal estate amounted to £6,612.7s.6d, approximately £785,000 today.

Objects from the Royal Charter wreck are in the collection of the Merseyside Maritime Museum on display in the Emigrants to a New World gallery. Even today, 150 years later, scuba divers occasionally find pieces of gold on the seabed. Many pieces of the wreckage can still be seen at the base of the rocks at low tide.

The terrible storm in 1859 which was the worse storm of the 19th century also accounted for the loss of a further 131 ships that night. During the storm the wind speed went from Storm Force 10 to Hurricane Force 12 and the Royal Charter was no match for its strength.

However, some good came out of this tragedy. Robert FitzRoy was a career naval commander who had been captain of the Beagle when Darwin made his epic scientific observations in the 1830s. He had retired from active service in 1850 with the rank of Vice-Admiral and was asked to set up a new department to deal with the collection of weather data at sea. He was very enthusiastic about this work but many people were sceptical of its value. However, the wreck of the Royal Charter changed attitudes and FitzRoy was able to introduce many ideas. He developed charts to allow predictions to be made, which he called ‘forecasting the weather’. Fifteen land stations were set up to use the new telegraph to transmit to him daily reports of weather at set times. The first daily weather forecasts were published in The Times in 1861.

The 1859 storm also resulted in the Crown issuing storm glasses then known as “FitzRoy’s storm barometers” to many small fishing communities around the British isles. In 1860 FitzRoy introduced a system of hoisting storm-warning cones at the principal ports when a gale was expected. He ordered ships to stay in port under these conditions.

This was the forerunner of the modern Meteorological Office, a worthy memorial to the loss of the Royal Charter.

These signals are still used at St Helier in Jersey. The Meteorological Office sends weather warnings to Jersey Heritage and they maintain the tradition by notifying the duty signalman who hoists the relevant warning.