The origins of Chadkirk Chapel are lost in the Mists of Time, or, more accurately, lost in Myths and Legends. However, it is safe to say that it is probably the oldest ecclesiastical building in the borough as well as holding a Grade II* classification. St Chad was a key figure introducing Christianity to Mercia and his name is associated with numerous churches, religious foundations and settlements. He was extremely hard-working and, when he became bishop, visited all parts of his See on foot “preaching the Gospel and seeking out the poorest and most abandoned persons in the meanest cottages and in the fields that he might instruct them.”

Chadkirk Chapel

St.Chad of LichfieldThe River Goyt for a long time formed the northern boundary of Mercia and tradition has it that he came to this area in person to bless the well and that in Saxon times there was a religious foundation at Chadkirk associated with him. The very name ‘Chadkirk’ implies a close connection with the saint from its earliest foundation and the presence of St Chad’s Well lends credence to that belief. The Davenport family who owned Goyt Hall and various land in the area claimed to have founded the chantry at Chadkirk but there was probably a significant presence there already. The earliest written record relates to William de Chaddekyrke in 1347.

St.Chad of LichfieldThe River Goyt for a long time formed the northern boundary of Mercia and tradition has it that he came to this area in person to bless the well and that in Saxon times there was a religious foundation at Chadkirk associated with him. The very name ‘Chadkirk’ implies a close connection with the saint from its earliest foundation and the presence of St Chad’s Well lends credence to that belief. The Davenport family who owned Goyt Hall and various land in the area claimed to have founded the chantry at Chadkirk but there was probably a significant presence there already. The earliest written record relates to William de Chaddekyrke in 1347.

The advent of Protestantism in the sixteenth century resulted in the suppression of almost all chantries. When the chapel was valued in 1535 Ralph Green, the chaplain, held lands and tenements valued at £4 1s 4d out of which he paid one tenth, presumably the tithe, to the rector of Stockport. Ten years later the Act of 1545 defined chantries as representing misapplied funds and misappropriated lands so henceforth all chantries and their properties would be at the disposal of the king. A new valuation was made and this time it totalled £6 13s 4d - an increase of over 50% in thirteen years. Within that total goods and ornaments were valued at 16s 8d and lead and bells 6s 8d. Interestingly there was a nil value for plate and jewels. This could be because the chapel was poor or, just as likely, any portable valuables had been removed by interested parties. The Davenport family contested the confiscation, arguing that the chapel did not belong to the Church but was their private property. Their claim was conceded and eventually the chapel and its endowment were restored to them by 1559. As a result of the dispute and later lack of interest the building fell into disuse but by the 1640s some marriages were recorded and the chapel was sufficiently well-established for the post of a regular minister to be offered.

Thomas  Chadkirk Well DressingNorman was appointed in the early 1650s but the Act of Uniformity in 1662 imposed a problem for many clerics. The Act prescribed the prayers and ceremonials to be followed and many preachers were ejected from the Church of England. The chaplain to the Ardern family, John Jones, who had preached at several churches in the district, now concentrated his nonconformist activities at Chadkirk. He even offered a refuge there to Samuel Eaton, a well-known independent preacher from Dukinfield.

Chadkirk Well DressingNorman was appointed in the early 1650s but the Act of Uniformity in 1662 imposed a problem for many clerics. The Act prescribed the prayers and ceremonials to be followed and many preachers were ejected from the Church of England. The chaplain to the Ardern family, John Jones, who had preached at several churches in the district, now concentrated his nonconformist activities at Chadkirk. He even offered a refuge there to Samuel Eaton, a well-known independent preacher from Dukinfield.

After the passing of the Toleration Act of 1689, Gamaliel Jones, the son of John Jones was licensed as a nonconformist preacher at the chapel. It was now officially registered as a dissenter’s meeting house. There were several reasons for the persistence of nonconformity at Chadkirk. Bishop Wilkins was not unsympathetic and with his ‘soft’ approach he induced many nonconforming ministers to conform. In addition Chadkirk was remote and irregularities could pass unnoticed. Theoretically it was a private room in a private dwelling so attendance could pass as private visits to the family.

This was a period of great religious turmoil and although the dissenters, unlike the Catholics, were not banned, they did not have full statutory rights. In 1705 the nonconformist congregation was evicted by the Church of England and the building ceased to be a chapel for thirty years. Never slow to take advantage of an empty building, a local farmer then used it as a cowshed. However, in 1747, after a proposal to the rector of Stockport, a subscription was raised, the chapel was restored and a curate appointed. It was obviously a popular move as a bellcote was added in 1750 and ten years later the capacity was expanded by building a gallery at the west end.

As always, circumstances change with time and by 1865 the chapel was too small and the population of Romiley had moved towards the north, influenced by the new railway station.

A new church of St Chad was built at Cross Moor and the old chapel abandoned. Nevertheless, there was still life in the old dog. In 1876, after a decade of disuse, the chapel was restored at the instigation of the vicar of St Chad’s and Mr Syddall, the owner of the Chadkirk print works. As part of this work the gallery, the wooden rood screen separating the chancel from the nave and the old pews were all removed. Along the centre of the nave a row of graves was re-laid, bordered by black and yellow tiles. In the chancel the grave slab marking the Syddall family vault was incorporated within the new floor.

Chadkirk Festival

The building was now, in effect, the private chapel of the Chadkirk Print Works. Services were held on Sunday afternoons for the Syddall family and their employees but these gradually became irregular. After 1920 there were only occasional services and in 1972 Bredbury & Romiley UDC bought both the chapel and the farm, Stockport MBC acquiring it in turn when it took over responsibility in 1974.

The archaeological record reinforces this history.

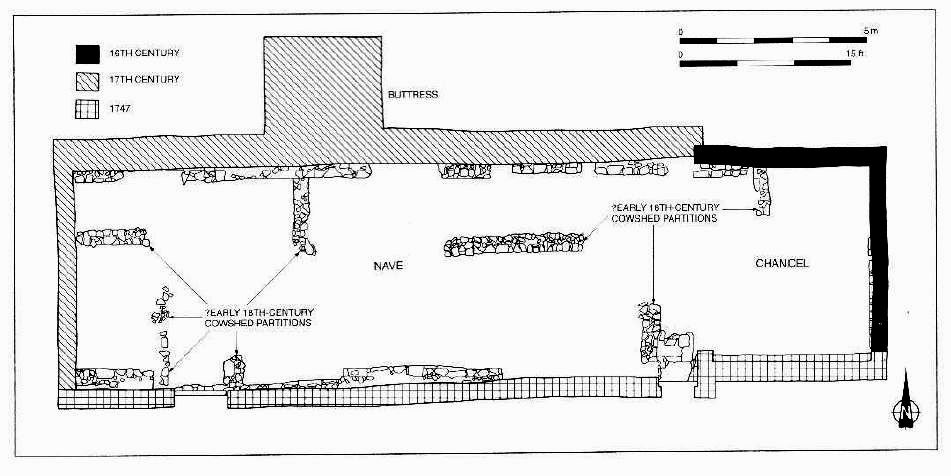

In 1994 the Greater Manchester Archaeological Unit carried out excavations at the chapel. It is alighned east-west and comprises a rectangular nave with a slightly narrower chancel. The north and east walls of the chancel (black in the hand drawn plan) are of timber framing on a stone plinth and date from the early 1500s. The original chapel would have looked like this all round.

The west and north walls of the nave were replaced when the chapel was renovated in the 1630s. This involved dismantling the earlier stone plinths though the original footings were retained and the new wall built up from these.

The evidence for the chapel being used as a cowshed is hidden but the 1994 excavation showed that the interior had been laid with cobbling set into sandy clay. Within this floor were sandstone footings (shown in the above plan) which appear to represent dividing walls making small bays. The upper parts of these walls were possibly in the form of wooden partitions.

New loft gallery depicting the life of St. Chad. Chadkirk Chapel

The major renovation of 1747 saw the complete rebuilding of the south wall of the chapel (square hatching in the above plan.) This wall contains the two entrances to the chapel and two round-headed windows in the nave plus one in the chancel. It was a solid construction as ten years later it supported a dormer window above the west door and a gallery at the west end of the nave to accommodate a larger congregation. It was at this stage that many of the gravestones were rearranged.

Changes after this were more concerned with taking things away rather than adding or improving matters. In 1876 the gallery, the rood screen and the pews were removed. After 1920 many of the other fixtures and fittings went. However, it is more than likely that the chapel would have disappeared entirely by now if Bredbury and Romiley UDC and subsequently Stockport MBC had not taken possession of it. Stockport has maintained it well and made improvements as well as a thorough structural and archaeological survey. Finishing touches include a new stained glass window for the East wall of the chancel and a small font of modern design which serves to bring attention to the connection between the chapel and St Chad’s Well.

An Autumn Saturday, November 2019.

A protest meeting on the proposed closure, at the time, of December 31st

It just seems wrong that after almost fifty years of responsible stewardship by SMBC that the chapel should now be mothballed for the sake of miniscule savings. There is still a healthy local interest in the chapel as can be seen by the attendance at the meeting to discuss its future (see the above picture). Surely we can keep it open regularly at weekends if nothing else? Why should private weddings be the only people privileged to see it?

Neil Mullineux - January 2020

Photos: Bill Beard, David Burridge, and Arthur Procter