Chadkirk Printworks

In September 1755 William Wright leased a plot of land from George Nicholson, the owner of the Chadkirk Estate, for a period of fifty years. He wanted to build a mill for textile finishing - bleaching, dyeing and printing. At the time, although Britain had a reputation for producing raw materials such as wool and flax it was still only a cottage industry when it came to producing finished textiles. If woven cloth was to be bleached and dyed it was sent to Holland and the finest printed cottons came from India - no local producer could match them for quality. But things were beginning to change. Although cotton would not come into its own until the technological developments of the 1760s and 70s, the production of cloth was becoming more sophisticated. Fulling mills were improving the quality of finished cloth, printing of textiles was spreading from the south of England and small bleachworks were experimenting with new chemicals.

|

|

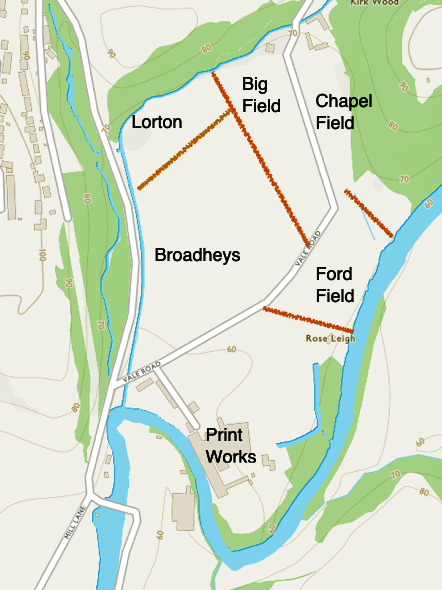

The original Chadkirk works were “of rude construction, with scarcely any building more than one storey high except a long building two storeys high.” However, the main business at first was bleaching. The traditional process consisted of steeping the cloth in alkaline lye then spreading it out on grass to expose it to sunlight. This process would be repeated five or six times and the whole procedure would take several months.

The site was ideal for this type of operation. The Goyt was clean and pure as there were no other factories using its water at that time and the factory was surrounded by extensive flat meadows. Although the above is a modern map the field boundaries have not changed in two hundred years. This combined bleachworks and printworks was one of the oldest in the north of England and possibly the oldest. The earliest date for a print works at Bamber Bridge, near Preston, which is generally regarded as the first in the north west is 1764. However, William Wright’s enterprise did not last long; in 1765 he was declared bankrupt. The following year his stock of printed cottons and print designs were put up for sale, followed a few months later by the already extensive buildings.

The next occupant was a partnership called Fosbrooke and Wroe who manufactured chintzes. These were printed calico textiles, glazed on one or both sides. The market for these collapsed in 1786 and Fosbrooke dropped out but the Wroe family carried on in a variety of guises for thirty years. The first iteration was Wroe, Greenaway and Wroe, a firm which printed textiles. They brought in a number of workers from London who created quite a stir by wearing scarlet coats, top boots and cocked hats. As they commanded much higher wages than the locals there was considerable ill feeling. Following the departure of Greenaway a new partnership was formed, Wroe and Kershaw. In 1799 a great flood caused considerable damage to the works and was possibly a contributory factor to the dissolution of that partnership. The next company to take control was Wroe and Duncroft but this was dissolved on 1st April 1808 to be replaced by Wroe Gray and Wroe. Wroe and Duncroft, however, had a large power loom establishment in Westhoughton employing about 250 people so they must have decided that printing was not for them. Nor was it for Wroe Grey and Wroe because that partnership, having suffered labour and financial troubles, failed in 1816.

This was a long list of change and failure but it was not unique to this establishment. Both the bleaching and the printing industries were going through enormous technical change at this time and Europe was experiencing radical upheavals, first with the effects of the French Revolution and then with the Napoleonic Wars which lasted from 1799 to 1815. In 1785 Claude Berthollet recognised that newly discovered element chlorine could be used as a bleach and by 1799 Charles Tennant, the Scottish industrialist, had patented bleaching powder. This chemical treatment resulted in extraordinary improvements in the process, reducing bleaching times to less than 24 hours and allowing many firms to do their own bleaching.

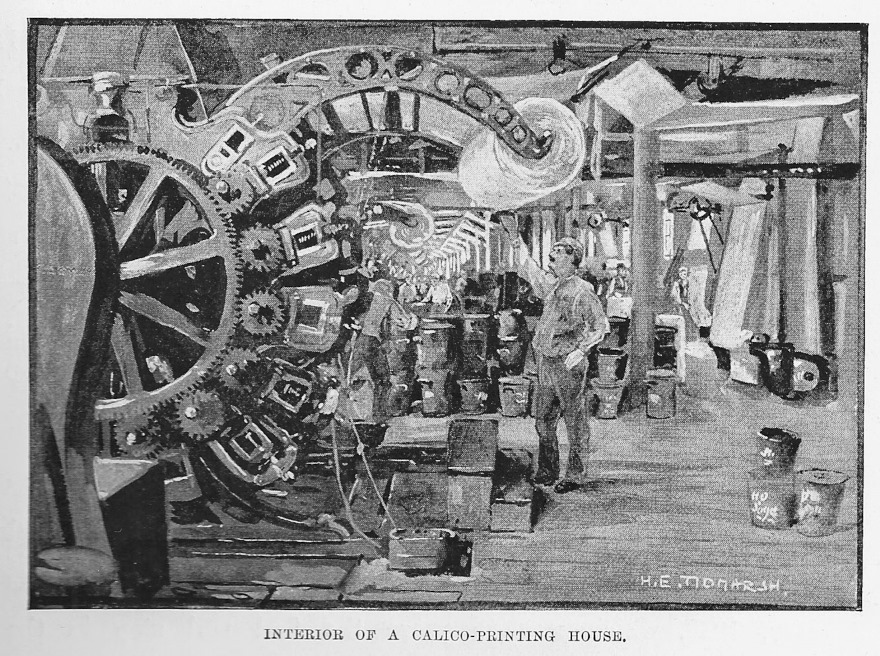

Similar advances were being made in the printing of textiles; advances whichbrought many new competitors into the industry and put pressure on the incumbent firms to keep abreast of the technology. The standard method of block printing was slow and labour intensive but in 1783 Thomas Bell patented a technique using copper rollers and this was taken much further by John Potts in New Mills in 1812, using a copper-engraved master to produce rollers to transfer the inks.

As a result the works at Chadkirk stood empty until in 1824 they were revived by Joseph Syddall and his partner, Robert Addison. They acquired the dilapidated works for what was no more than a farming rent and rebuilt it. They installed two cylinder printing  Orange Tree Housemachines and produced a limited product range at first, concentrating on single colour handkerchiefs and similar items. By 1840 this partnership too declared bankruptcy but Joseph Syddall obviously had confidence in the venture. He restarted it soon after as Joseph Syddall and Sons and it apparently prospered because over the next few years he extended the works. The Syddall family were to dominate the business for the next sixty years with the various branches often exchanging residences between Rose Leigh nearest to the works, Chadkirk House and the farm, and Orange Tree House in Church Lane, Romiley.

Orange Tree Housemachines and produced a limited product range at first, concentrating on single colour handkerchiefs and similar items. By 1840 this partnership too declared bankruptcy but Joseph Syddall obviously had confidence in the venture. He restarted it soon after as Joseph Syddall and Sons and it apparently prospered because over the next few years he extended the works. The Syddall family were to dominate the business for the next sixty years with the various branches often exchanging residences between Rose Leigh nearest to the works, Chadkirk House and the farm, and Orange Tree House in Church Lane, Romiley.

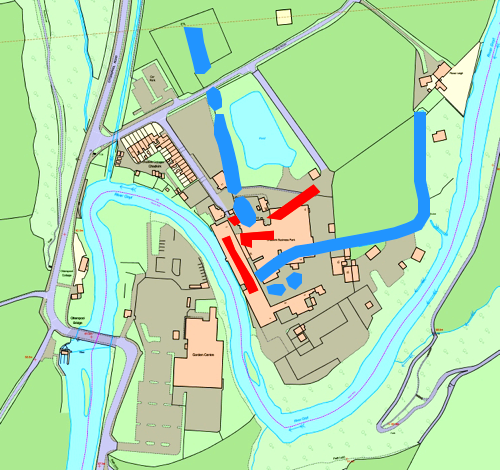

All seemed to be going well but on 17th September, 1849 a large part of the works was destroyed by fire. There were several blocks, the largest being 78 feet long by 18 feet wide, three storeys high at one end, two at the other. In this building were printing machines, a valuable calendaring machine, a dash wheel for soaking cloth and various other appliances. One of the upper storeys was used as a drying shed. At three o’clock in the morning the watchman sounded the alarm but although appliances came from Andrew’s Mill in Compstall and from Woodley, the building was completely gutted. The damage was estimated at around £2000 (£250,000) but fortunately they were insured and rebuilding began almost immediately.

The map shows the extent of the works at the time of the fire in 1849 (bright red) superimposed on the later extended building (orange). The darker blue shows water courses used by the works at that time.

The map shows the extent of the works at the time of the fire in 1849 (bright red) superimposed on the later extended building (orange). The darker blue shows water courses used by the works at that time.

Joseph died in 1856 but his two sons, Richard and James, took over. At first Richard was the nominal head of the business but by 1871 James was in charge and Richard was running the family farm. Whether this was an amicable arrangement or the result of a family feud we do not know. However, one member of the extended family, a cousin Joseph, was back in favour. In 1852 he had eloped with the housemaid, Agnes Alexander. The couple made their way to Gretna Green, looked for a chapel or church, and, on not finding one, refused to be married by the blacksmith and took the train to Liverpool. The couple rented a house there for two months but then Syddall left without paying the rent. Agnes brought in solicitors and his father eventually paid the rental. However, she was pregnant so, when the child was born, she took him to court for breach of promise and was awarded £50 (£6500 now.) It is not appropriate to relate the details in a family website such as this but a report of the court proceedings can be accessed here if needed for research purposes.

Read Report (col 3)

Although it must have caused a stir when the case went to court, by the time of the 1861 census Joseph was living in Romiley, married to Mary with four children and employed in the print works.

James Syddall died at his home in Romiley in 1896. Three years later, in 1899, the Calico Printing Association (CPA) took over the works. This was part of a much bigger movement towards consolidation in the cotton industry. Between 1896 and 1900 there were 18 large mergers in the cotton and woollen industry. Some were mergers between large diversified companies looking to achieve economies of scale but most were horizontal combinations uniting smaller firms engaged in a single activity. The object here was to rationalise the industry and reduce the excess capacity. The CPA was an amalgamation of 46 printing companies and 13 textile merchants. As well as Syddall Brothers and Strines Printing Company a number of the printing works in Hayfield and the Sett Valley were part of the amalgamation. Syddall Brothers had been a successful business over the time of the family ownership but it had never really grown. Employment varied between 110 and 140 over the period and this typically comprised 90 men, 25 boys (under 18) and 20 women. The Syddalls had made a comfortable living from the company but they were not in the same league as the ‘cotton barons’ - the Carvers, the Hodgkinsons, the Andrews and the Shepleys.

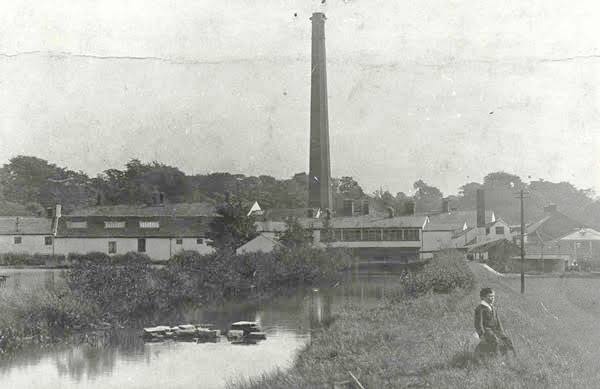

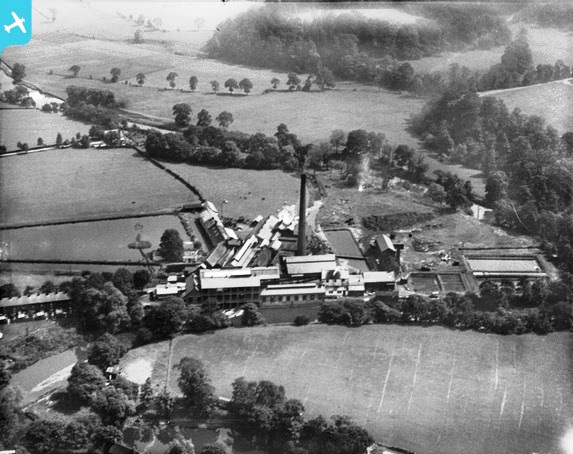

Chadkirk Printworks in 1928

For a time the family retained an interest in the business as after the CPA takeover, Richard Syddall stayed on as manager but he was succeeded by a succession of career men. Until the First World War the works produced goods mainly for export but it later moved to the manufacture of shirtings for the home trade. In 1929 the CPA ended printing at Chadkirk and over the next three years converted the buildings into a dye works. Chadkirk was probably selected for conversion because of the reliable supply of water from the Goyt. The works reopened in 1932 and it specialised in the high grade silk and rayon market. The fabrics were woven at Waterside Mills and dyed and finished at Chadkirk. However, the waters of the Goyt were so polluted that a water purifying plant had to be built. Despite these improvements making Chadkirk one of the finest works in the country, the manufacturing orders gradually declined and the works finally closed in the 1970s. It still lives on as a business park, hosting many small companies but its role in the cotton industry has passed into history.