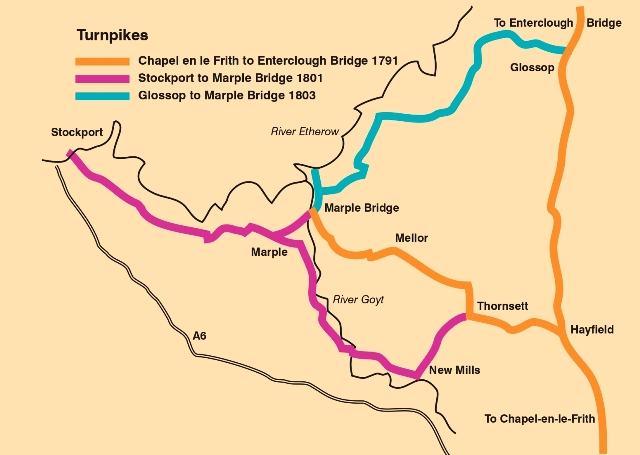

In the early days of the industrial revolution the roads around Marple and Mellor were atrocious - deeply rutted farm tracks that were difficult to use in summer and almost impossible in winter. No wonder the area was a rural backwater. However, in a period of little over ten years at the turn of the nineteenth century it suddenly had the use of three turnpikes and a canal.

The original route from the warehouse to Mellor Mill

St. Martins Toll House, note the side road

St. Martins Toll House, note the side road View from the other side of the gate

View from the other side of the gate

The first of these was actually a spur of a major turnpike running from Chapel-en-le-Frith to the Longdendale valley where it linked with a major cross-Pennine route over the Woodhead Pass. This spur ran from Hayfield through Thornsett and Mellor to Marple Bridge. Soon after this Samuel Oldknow was instrumental in organising a turnpike from Stockport to New Mills passing through Marple. This route took advantage of repairs and improvements that Oldknow had already made to bridges at Fogg Brook and Dan Bank, for which he was compensated by the turnpike trust. However, he did not get things entirely his own way as he had hoped to route the turnpike past his Mellor Mill on the way to New Mills but he was outvoted and the turnpike took an alternate route along the ridge.

The third turnpike also involved Samuel Oldknow but he did not play quite such a dominant role. Other local worthies such as Nathaniel Wright, Thomas and George Andrew and William Radcliffe were also trustees for a turnpike from Marple Bridge to Glossop (with a small spur to Compstall.)

The third turnpike also involved Samuel Oldknow but he did not play quite such a dominant role. Other local worthies such as Nathaniel Wright, Thomas and George Andrew and William Radcliffe were also trustees for a turnpike from Marple Bridge to Glossop (with a small spur to Compstall.)

A timeline demonstrates in just how short a period these transport developments were achieved.

- 1791 Marple Bridge to Hayfield turnpike

- 1797 Upper Peak Forest Canal opened

- 1797 First lime kiln operational

- 1798 Lower Peak Forest Canal opened (as far as aqueduct)

- 1800 Marple aqueduct officially opened

- 1800 Marple Lime Kilns fully operational

- 1801 Marple to Stockport and New Mills turnpike

- 1803 Marple Bridge to Glossop turnpike

- 1804 Marple Locks completed

- 1805 Peak Forest Canal open throughout its length

In just under fifteen year this district had welcomed three important toll roads and an important canal. After a millennium as a rural backwater, the people of this area must have felt that they were at the centre of the universe.

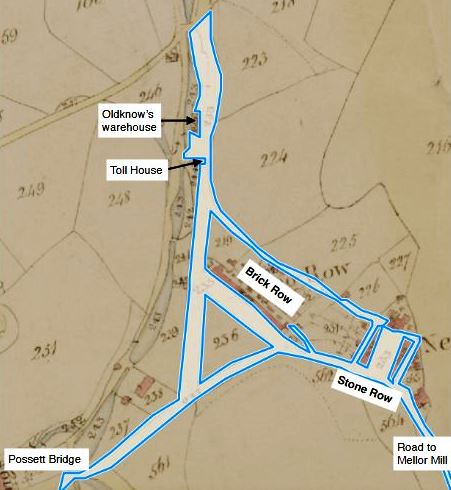

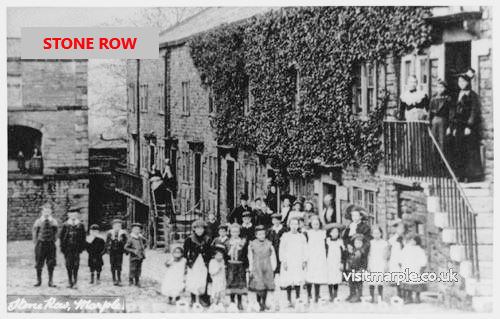

[click the image for a view from a modern version of this area]However, there was a fourth turnpike in Marple, this time a private one; private in the sense that it did not require an act of Parliament to authorise it. Samuel Oldknow had a lot of interests in the area. As well as Mellor Mill and the lime lilns, he had a warehouse on the canal at Lock 9 which acted as a transhipment point for both raw material and finished goods. In addition he had built workers’ housing at Brick Row and Stone Row. Once the canal was functional and the warehouse built, the obvious thing to do was build an all-weather road between the warehouse and the mill to facilitate the movement of goods. The road could also serve the workers’ housing, that was planned, and the lime kilns which had been in full operation since 1800.

[click the image for a view from a modern version of this area]However, there was a fourth turnpike in Marple, this time a private one; private in the sense that it did not require an act of Parliament to authorise it. Samuel Oldknow had a lot of interests in the area. As well as Mellor Mill and the lime lilns, he had a warehouse on the canal at Lock 9 which acted as a transhipment point for both raw material and finished goods. In addition he had built workers’ housing at Brick Row and Stone Row. Once the canal was functional and the warehouse built, the obvious thing to do was build an all-weather road between the warehouse and the mill to facilitate the movement of goods. The road could also serve the workers’ housing, that was planned, and the lime kilns which had been in full operation since 1800.

Oldknow, like many of his entrepreneurial contemporaries, had a wide range of interests outside his business activities. Agriculture, science, architecture, engineering, all took his interest and were much more than hobbies. He became interested in road construction because of his plans to build a road and he even wrote a short treatise on road construction, detailing the slopes necessary for good drainage and suggesting ways for vehicles to use the whole carriageway in order to minimise rutting.

Deciding on the right of way was no problem as at that time. Oldknow owned all the land between the warehouse and the mill. With his entrepreneurial instincts he decided to try to recoup some of his expenditure by charging a toll for the use of the road. Most of the traffic would be to or from his own enterprises but there would also be others who could and would want to use the facility. Normally a toll road would require an act of Parliament and all three of the toll roads in the area to that date had initiated appropriate legislation. However, as all the land involved was owned by one person, Oldknow himself, there was no need to purchase other land and he could do what he liked.

Brick Row, Red Row, and Stone Row were all built by Oldknow for his workers

Brick Row, Red Row, and Stone Row were all built by Oldknow for his workers

He built the road to his own specification, seven yards wide with an incline of two inches in the yard across the whole width. As it was wide enough to allow free movement across the full width, it would wear much more evenly and consequently help drainage. Rainfall runoff would flow to the lower edge and not collect in ruts. The higher side would be a natural path for foot-passengers.

The route went, in terms of current street names, [see map] due south from the warehouse, following St Martin’s Road until it reached Oldknow Road. It then turned south west and terminated at Possett Bridge. As far as we can tell, that is as near as it came to the lime kilns; it did not follow the route of the temporary tramway (across the Recreation Ground) which would have led it more directly to the lime kilns. However, the main route had already deviated towards the mill well before the road left St Martin’s Road. About half-way along it veered to the left and followed a route to where Faywood Drive meets Arkwright Road. It is along this short stretch that Brick Row was situated. The road then followed Faywood Drive, past the end of Stone Row and down Lakes Road to the bridge over the Goyt and to Mellor Mill.

A toll house was built immediately to the south of the warehouse. This had the dual function of charging tolls to some of the canal traffic as well. One side of the building projected into the road with a gate attached, extending right across the road to stop all vehicular traffic. At the back of the house, which was adjacent to Lock 10, a set of steps led down to the water level to enable an easy exchange with the boat operator. Most canal traffic passing through this point would have already paid a toll at Top Lock but boats coming from the lime kilns would have come into the main reach at Possett Bridge and they would have been asked to pay.

There are no physical remains showing where other tolls were levied but we know that charges were made to cross the bridge over the Goyt near the mill. It is also possible that there was a toll house at the end of Stone Row, but we cannot be certain of that.

Unfortunately there are no records of the tolls that were charged, the revenue from these tolls or the type of goods that were involved. We don’t even know how long these charges were levied, though it does seem that they had probably fallen into disuse by the middle of the century. However, the idea of a toll road, its implementation and the concept of developing additional revenue streams sheds further light on Oldknow’s abilities and achievements. As well as enterprising and ambitious he was able to harness his varied interests and combine them with lateral thinking; a true Renaissance Man.

Text by Neil Mullineux - September 2022

David Burridge - contemporary photographs

click any image below to view a larger version