THEY ALSO SERVE

Forewoman Sarah E Maddocks 9904 QMAAC

During the 18th and 19th centuries, soldiers’ wives often accompanied their husbands to the battlefield. A handful of women even disguised themselves as men to join up.

A WAAC cricket team at Etaples, 1 May 1918. Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum (IWM Q 8754)

At the outbreak of WWI, women were eager to prove that they too could support the war effort. Initially, the British government was reluctant to involve women; the prevailing attitude was that they were not skilled or resilient enough for traditional military work.

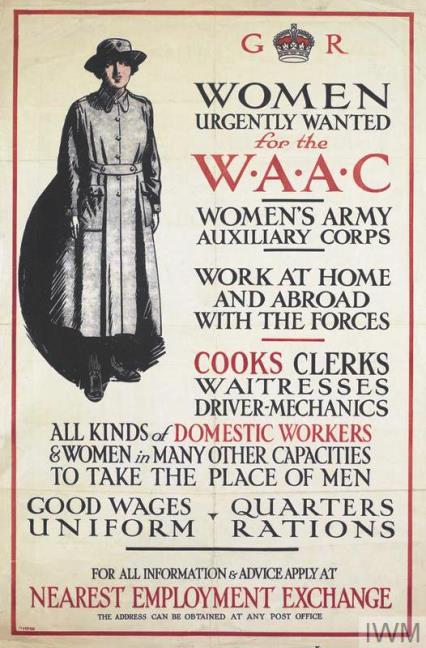

poster image courtesy of the Imperial War MuseumThe turning point came in 1916, when the Department of National Service considered calling up men in their 50s to release more soldiers for the front line. They soon realised this would not raise the number of men needed and so, in 1917, the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) was set up, with Dr Mona Chalmers Watson as its first Chief Controller. A noted suffragette, she was the first woman to receive an MD from the University of Edinburgh and she had been instrumental in proposing this corps.

poster image courtesy of the Imperial War MuseumThe turning point came in 1916, when the Department of National Service considered calling up men in their 50s to release more soldiers for the front line. They soon realised this would not raise the number of men needed and so, in 1917, the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) was set up, with Dr Mona Chalmers Watson as its first Chief Controller. A noted suffragette, she was the first woman to receive an MD from the University of Edinburgh and she had been instrumental in proposing this corps.

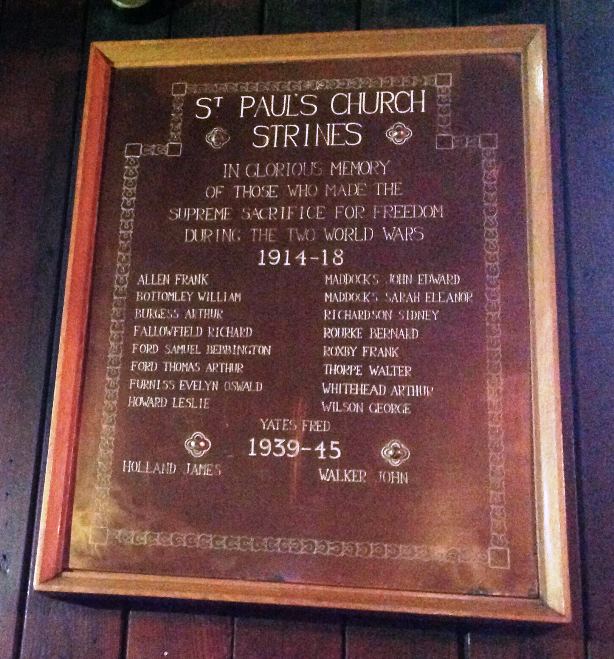

One such WAAC was Sarah Eleanor Maddocks, whose name is recorded on this plaque in St Paul’, Strines alongside that of her brother, John Edward, a private in the Royal Scots Fusiliers, who was killed on the Somme in 1916. Their names are also listed on a Memorial Scroll that predates the plaque.

Sarah was born in Stockport, in 1886, the daughter of James and Mary Maddocks. James was a postman, eventually becoming an Assistant Inspector of Postmen. In 1901 the family were living at 6 Chadwick Street, Marple. Ten years later, Sarah had left home and was working as a housemaid for the Robinson family at Thorncliffe House, 183 Buxton Road, Stockport.

We don’t know exactly when Sarah enlisted, but women were restricted to ‘feminine’ roles, such as store work, administration, and catering. At first the WAACs were confined to service in Britain but this was quickly expanded to France. Impressed with the WAAC’s work, Queen Mary became its patron in 1918. The corps was renamed Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps (QMAAC) to reflect its fine conduct during the German Spring Offensive of that year.

QMAAC Chief Controller Lily Davey spoke for all these volunteers when she said in 1920:

“We felt we were pioneers, and it was up to us to make good and to prove what women could do. I am sure the discipline, pluck and grit learnt then will help us in whatever the future has in store. Also, we have learnt what comradeship means in the widest sense.”

Forewoman Sarah Eleanor Maddocks died of pneumonia on the 7th March 1919 at Rugeley Camp, Staffordshire and was buried in a family grave at Stockport Cemetery. There is no official policy as to which names are included on a war memorial but many of them commemorate those who died as a result of disease whilst engaged in military service. Sarah’s service is rightly recognised in the same way as that of her brother.

|

|

Sarah and John are remembered on the memorial in St Paul’s Strines as their father had moved to 86 Hague Bar Road, Strines, where he lived for the rest of his life.

To learn more, follow the link to the National Army Museum: www.nam.ac.uk and search Queen Mary’s Auxiliary Army Corps.

www.findagrave.com links to a page showing Sarah’s Grave, Stockport Cemetery

Hilary Atkinson, November 2020

Further Reading:

On this website:

Elsewhere:

- Woodville Hall - Memories of a Wartime Evacuee

- Marple Schools WWI Roll of Honour

- Monty - A Marple Connection

- The Story of the Grave of the Unkown Soldier on the English Heritage website

On 10 November 1920, the body of an unknown British soldier was exhumed in Flanders and with due solemnity returned to Britain for burial the next day, when the Cenotaph in London was due to be unveiled by King George V.

This montage of newsreel footage and archive photographs, edited by the Archive, tells the story. The accompanying music we have added is a 1910 recording of Handel’s “Funeral March”, played by the Band of the Coldstream Guards, together with two 78rpm gramophone records made inside Westminster Abbey during the Burial Service and issued by Columbia records. These were recorded using an experimental electrical recording system - the first electrical recording using a microphone of a choir ever made. Thirty single-sided records were recorded but, as the results were rather inferior, only these two discs were ever issued. They feature the choir of Westminster Abbey, directed by Sir Sydney Nicholson.