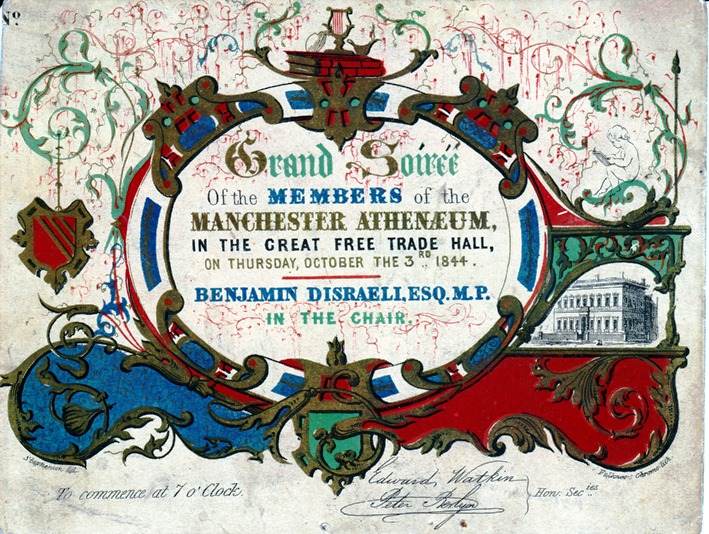

When searching the Archives, I occasionally come across something unusual and seemingly unconnected to the Society, such as this invitation. Why is it there, and what is its connection to Marple? It is unlikely we will ever know for sure, but perhaps a clue is handwritten on the back: ‘Edmund Buckley Esq MP’. I shall come back to Mr Buckley but first, let’s consider this invitation from The Athenaeum Society of Manchester to attend a grand soireé in the Free Trade Hall under the chairmanship of Mr Benjamin Disraeli, MP.

When searching the Archives, I occasionally come across something unusual and seemingly unconnected to the Society, such as this invitation. Why is it there, and what is its connection to Marple? It is unlikely we will ever know for sure, but perhaps a clue is handwritten on the back: ‘Edmund Buckley Esq MP’. I shall come back to Mr Buckley but first, let’s consider this invitation from The Athenaeum Society of Manchester to attend a grand soireé in the Free Trade Hall under the chairmanship of Mr Benjamin Disraeli, MP.

The AthenaeumThe Manchester Athenaeum Society was an organisation set up in 1835 to promote ‘the advancement and diffusion of knowledge’ amongst the citizens of Manchester. It concerned itself with organising events that would allow its members and others to improve their knowledge in general terms but specifically in the areas of politics, economics and literary events.

The AthenaeumThe Manchester Athenaeum Society was an organisation set up in 1835 to promote ‘the advancement and diffusion of knowledge’ amongst the citizens of Manchester. It concerned itself with organising events that would allow its members and others to improve their knowledge in general terms but specifically in the areas of politics, economics and literary events.

One of the political movements at that time had been the formation of the Young England Group, an organisation of politically minded Conservative people who wanted to see a new philosophy of Conservatism. The group advocated bridging the widening gap between the upper and lower classes in society whilst emphasising respect for the Monarchy, the Church and longstanding traditions. The Tory party had been dominated by the land owning aristocracy who had little time for the working classes and these new industrialists, but Young England rejected this behaviour, favouring a more inclusive approach as described above which would later become known as ‘one nation Conservatism’.

Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli

The rising star and leader of the Young England Group was the MP Benjamin Disraeli who would later become Prime Minister. In promoting the ideas of Young England Disraeli had written in 1844, a political novel, Coningsby which had achieved great success across a wide section of Society. It is perhaps therefore not surprising that the members of The Athenaeum would have seen the whole idea of Young England as a subject to present to its members and their guests, and who better to chair such a gathering than the young Mr Disraeli fresh from the success of his new book.

I have been unable to find out whether it was the normal practice for the Society to arrange its meetings around a soireé but it would be nice to think that it was a way to bring an element of fun into a nonetheless serious subject. It may also have been a way of encouraging greater numbers to attend the meeting and for this particular gathering clearly large numbers were expected to want to attend as the chosen venue was to be no less a place than The Manchester Free Trade Hall, a large space used for public meetings, political speeches and concerts.

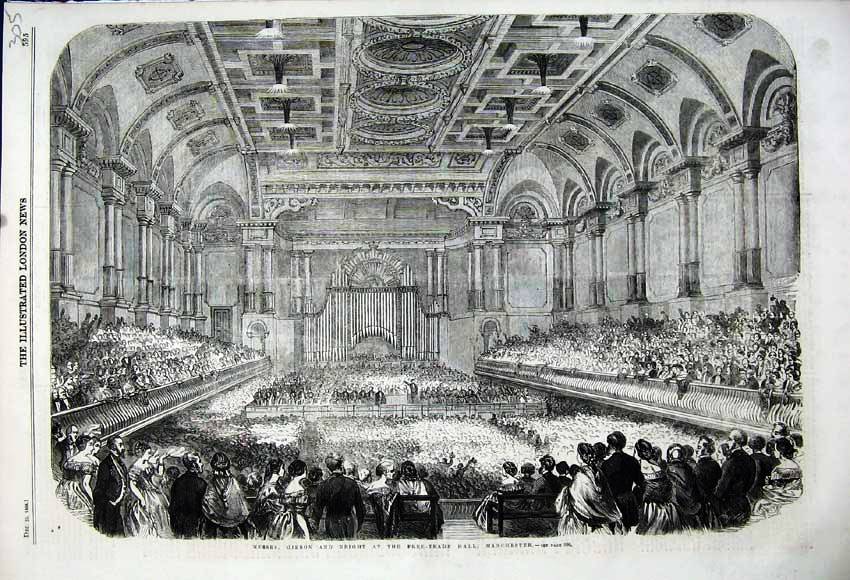

We know from the Times newspaper which reported on the meeting the next day that it was a great success. No fewer than ‘3,200 persons’ attended The Grand Soireé. Doors opened at 6pm and the Hall rapidly filled with ‘elegantly dressed ladies and gentlemen’. Just after 7pm Benjamin Disraeli took the chair and the speeches began. Other speakers included James Heywood, the first President of the Manchester Athenaeum and Richard Cobden, MP for Stockport who is best known for his successful fight for the repeal of the Corn Laws (1846) and his defence of free trade. Disraeli, in particular, was given nine rounds of applause and thanked profusely for presiding over the event.

At 11pm the floor of the hall was cleared of seats and the dancing commenced with ‘great spirit and continued with unabated vigour and elasticity to an early hour of the morning. Quadrilles, waltzes and polkas were danced to the band of The 5th Dragoon Guards. ‘Thus, brilliantly terminated the most extensive and interesting festivity of a purely literary chronicle which had ever been celebrated in this town’.

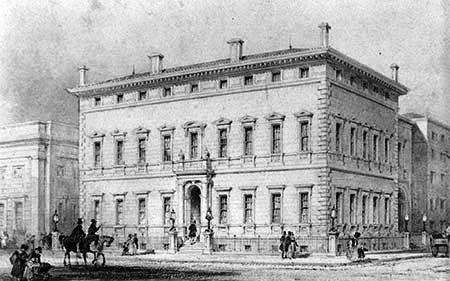

Free Trade Hall

It certainly sounds as though a good time was had by all but this meeting was significant, not just for The Athenaeum and Manchester but also for Benjamin Disraeli. The Athenaeum was the apogee of Manchester’s commercial and intellectual society and its members encapsulated the energy and growing self-confidence of a city that was recognised internationally as the first city of the industrial revolution. Three years after its foundation, the Society had built as its headquarters, an Italian palazzo building designed by Sir Charles Barry. One of the most notable architects of the day he went on to design the Houses of Parliament. The Athenaeum, a Grade II listed building, still stands today in Princess Street, part of the Manchester Art Gallery.

The Society invited Disraeli to this meeting as he was already a well-known writer and a rising MP. Any orator who stated that ‘Manchester is as great a human exploit as Athens’ would be bound to find favour in such company but Disraeli was outlining a new philosophy of Conservatism. Disraeli’s new manifesto of Progressive Conservatism struck a chord with many of the new class of industrialists represented in the Athenaeum.

It was not just ‘any old’ meeting. At this Grand Soireé Manchester was asserting its prominence in the new order in society that was making itself felt. Disraeli was trying to promote ideological change in the Tory party. This historic meeting in 1844 was the start of a major political realignment in Victorian Society.

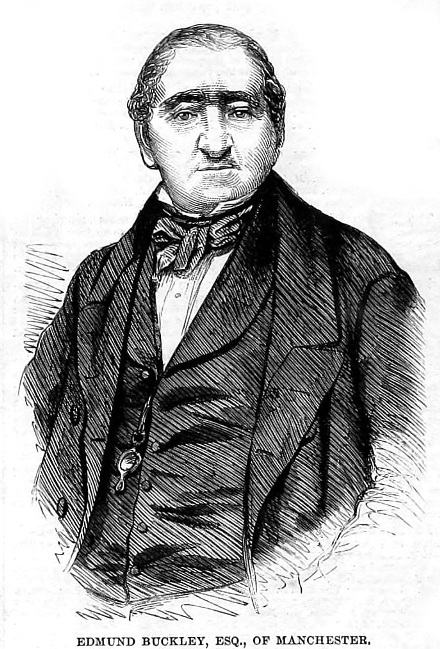

Edmund BuckleyAnd so I return to Edmund Buckley who was born in Saddleworth in 1780 and had a successful career as an industrialist owning iron works, collieries and cotton mills. He was also a Conservative MP for Newcastle-under-Lyme from 1841 to 1847 and from 1855 to 1860 Chairman of the Manchester Exchange. He died at his house in Ardwick in 1867. We know little about his private life except that he had 16 children, at least 8 of whom were illegitimate. Given his high profile as an industrialist and MP and his Manchester connections, it is reasonable to imagine that he was very much around at the time of the Grand Soireé and may well have attended the event. It is tempting to assume that the appearance of his name on the back of the invitation means that this was indeed his own personal invitation but that cannot be proved. The card in our archives gives no other clue as to how we came by it. Nowadays when we receive new material we try to establish from the donor as much information as possible as to what we are getting and its provenance but the card has probably been with us for a long time and no explanatory information exists. So we have no proof that he was at the event, whether he made a contribution to the discussions or even danced a quadrille, but he would certainly have known about it and, given his own background, been pleased to have observed even if from a small distance such a momentous occasion in the history of UK political thinking.

Edmund BuckleyAnd so I return to Edmund Buckley who was born in Saddleworth in 1780 and had a successful career as an industrialist owning iron works, collieries and cotton mills. He was also a Conservative MP for Newcastle-under-Lyme from 1841 to 1847 and from 1855 to 1860 Chairman of the Manchester Exchange. He died at his house in Ardwick in 1867. We know little about his private life except that he had 16 children, at least 8 of whom were illegitimate. Given his high profile as an industrialist and MP and his Manchester connections, it is reasonable to imagine that he was very much around at the time of the Grand Soireé and may well have attended the event. It is tempting to assume that the appearance of his name on the back of the invitation means that this was indeed his own personal invitation but that cannot be proved. The card in our archives gives no other clue as to how we came by it. Nowadays when we receive new material we try to establish from the donor as much information as possible as to what we are getting and its provenance but the card has probably been with us for a long time and no explanatory information exists. So we have no proof that he was at the event, whether he made a contribution to the discussions or even danced a quadrille, but he would certainly have known about it and, given his own background, been pleased to have observed even if from a small distance such a momentous occasion in the history of UK political thinking.