The Letters of Petty Officer Thomas Leach, R.N., 1911-1916

A photograph of Admiral John Rushworth Jellicoe (1859-1935) bidding farewell to Field-Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener (1850-1916) before his embarkation aboard the H.M.S. Hampshire, bound for Russia, Kitchener (third figure from right) was drowned when the Hampshire struck a mine off Orkney and sank on the 5th June 1916. Admiral Jellicoe is seen standing beside Kitchener.

Editor's note:

In 2019 Ann Hearle asked Geoff Higgins, a colleague in the Society's archive group, to look through the letters of her forbear Thomas Leach, to review and order the contents. The result of Geoff's work is presented here.

On the 5th June, 1916 the armoured cruiser H.M.S. Hampshire sailed from Scapa Flow bound for Archangel in Russia, carrying a high-level diplomatic team led by the Secretary for War, Horatio Lord Kitchener. The conditions were stormy and the sea so rough that Hampshire’s captain sent the two accompanying destroyers back to base as they could not keep up with cruiser. A little later the captain decided that the Hampshire should also return to port but on that fateful return journey the ship ran into a minefield, previously laid by a German submarine, and was sunk off the coast of Orkney. Kitchener and all his aides were drowned. Indeed, the loss of the Hampshire has been mainly remembered for this fact, attracting many legends and conspiracy theories around the death of a man who was still a national hero. It is sometimes overlooked that the sinking caused a huge loss of life amongst the Hampshire’s crew with only twelve survivors from a complement of some 750 men. Amongst those who lost their life was one of the ship’s Petty Officers, Thomas Leach, then aged 39, who had been serving in the Hampshire since January 1914.

Representation of the sinking of the Hampshire

A photo Leach had taken on shore leave in Singapore to send home to his motherWhen war broke out, Leach had been in the Navy for over 20 years having joined in late 1892 as a boy of 15. He had been born in 1877, the third child of John and Mary Ann Leach, although an elder sister Rosalie had died an infant before he was born. In 1881 the family was living in Golborne Terrace, Kensington and Tom had a younger sister Jessica [Jessie] aged 2. At that stage, his father was described as a Greengrocer’s assistant. Four years later his father died from the dreaded tubercular disease Phthisis which continually ravaged Victorian England. Clearly, the family was in challenging economic circumstances and Tom needed to leave school later in the decade to contribute to the family income. In 1891, aged 13, he was described as an errand boy. By this time, the family had moved to Cambridge Road, Willesden with Tom’s mother as the main breadwinner as a needlewoman with Tom’s elder sister Ellen assisting. Tom’s departure for the Navy the following year obviously helped the family financial situation. By 1901 the family had moved again to an address in Paddington by which time both Tom’s younger sisters were also working as dressmakers with their mother. From this somewhat unpromising background, Leach built a successful career in the Navy, steadily working his way through the various seamen’s grades and earning a character assessment of “Very Good” from the great majority of his commanding officers. Having started as a “boy, second class” he reached the rank of Petty Officer , First Class in May 1906 and maintained that rating for the rest of his career.

A photo Leach had taken on shore leave in Singapore to send home to his motherWhen war broke out, Leach had been in the Navy for over 20 years having joined in late 1892 as a boy of 15. He had been born in 1877, the third child of John and Mary Ann Leach, although an elder sister Rosalie had died an infant before he was born. In 1881 the family was living in Golborne Terrace, Kensington and Tom had a younger sister Jessica [Jessie] aged 2. At that stage, his father was described as a Greengrocer’s assistant. Four years later his father died from the dreaded tubercular disease Phthisis which continually ravaged Victorian England. Clearly, the family was in challenging economic circumstances and Tom needed to leave school later in the decade to contribute to the family income. In 1891, aged 13, he was described as an errand boy. By this time, the family had moved to Cambridge Road, Willesden with Tom’s mother as the main breadwinner as a needlewoman with Tom’s elder sister Ellen assisting. Tom’s departure for the Navy the following year obviously helped the family financial situation. By 1901 the family had moved again to an address in Paddington by which time both Tom’s younger sisters were also working as dressmakers with their mother. From this somewhat unpromising background, Leach built a successful career in the Navy, steadily working his way through the various seamen’s grades and earning a character assessment of “Very Good” from the great majority of his commanding officers. Having started as a “boy, second class” he reached the rank of Petty Officer , First Class in May 1906 and maintained that rating for the rest of his career.

During his time in the service Leach wrote regularly to his Mother, and to his sisters, particularly one of his younger sisters Ruby, even though on his own admission he was not a keen correspondent. These letters were clearly cherished at home and, remarkably, a number have survived. They were passed down through family members and eventually were given to Mrs Ann Hearle, a well-known local historian, then living in Mellor near Stockport, who is the granddaughter of Leach’s younger sister, Jessica. There are 36 letters in the collection in total, the vast majority of which were written during his service on the Hampshire and they form the basis of the present article. In 2019 Ann Hearle’s health was deteriorating and she asked me as a colleague in a local history group to look through the letters to review and order the contents. The letters were then transcribed and as far as was possible collated into their likely order. Although the content is generally unremarkable, the letters represent a contemporary voice, unusually from the lower decks of a famous ship, and give us a glimpse of life from an absorbing period of history.

The two most detailed letters in the collection come from the period before the First World War when Leach was serving on HMS Glasgow, a light cruiser launched in 1909. He joined the ship in September 1910 and served in her for two years. Glasgow was involved in the Battles of Coronel and the Falkland Islands in 1914 but by then Leach had transferred to the Hampshire. During his service in the Glasgow, the ship was mainly involved in patrol duty on the coast of South America. This involved several port calls and Leach describes some of them in the first letter of the collection. During this period, the ship sailed to South Africa to enter dry dock for repairs and re-fitting and the second, and most lengthy, of the letters was written to his sister Ruby from Simonstown in the then Cape Colony.

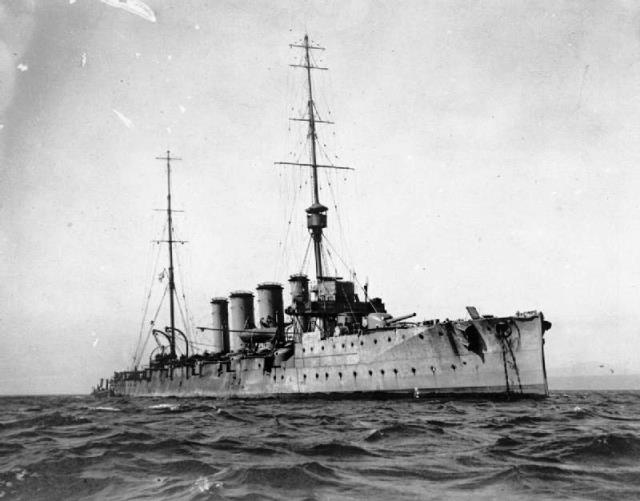

HMS Glasgow photographed in 1911 when Tom Leach was serving on her.

The first letter, undated but probably written in July 1911, recounts, to his mother, the crew’s visit to Buenos Aires where initially they spent a fortnight. Leach was very impressed with the modernity of the city, noting the electric trams and the great number of motor cars. The crew played several football and cricket matches against the crews of other ships and local teams, the latter helped by the large expatriate British community in the city and more widely in the country. The next stop for the ship was Montevideo and then on to Maldonado, also in Uruguay, but there the emphasis was on gunnery drills and practices. Leach realised, however, that his family’s thoughts would have been more focussed on home events, the Coronation of George V having taken place the previous month. He had read about the event from the newspapers his mother sent him regularly from home.

The streets of Rio-de-Janeiro around 1910

The next letter, again undated but sent from South Africa, almost certainly in either November or December 1911, gave more information about their previous time in South America, this time from their visit to Rio De Janeiro. Leach tells his sister that the ship’s company gave concerts on shore and that the last performance in Rio De Janeiro was attended by the President of Brazil and “ all the big bugs”. It was so well received that the performers were invited for a day out the next day. They were taken on a trip up the Corcovado mountain overlooking the city and then treated to lunch at a local hotel, where the sailors “finished everything they had, including the beer”. A detailed account of the activity of the Glasgow and her crew during the period 1910 to 1912 was compiled by William Ferguson, the Ship’s Chief carpenter, and Henry Lane, the Carpenter’s Mate, and published in 1912. The book gives full details of the incidents that Leach refers to and a cast list in the book for their theatrical performances includes Leach among the ship’s “orchestra” as one of two banjo players. The authors note that, on the performers’ day out the locals were bemused to see two vehicles full of British sailors having a sing song en-route to the accompaniment of banjos, so it seems that Leach took his beloved instrument with him up the mountain! Leach had included a photograph of the performers for his sister but unfortunately this has been lost. A photograph of some of the actors and singers in the ship’s performing company is included in the book of Ferguson and Lane referred to earlier but does not include Leach and the other instrumentalists.

Later in the letter, Leach also relates that he had visited Cape Town and Johannesburg. He found the former disappointing and he thought “almost played out” but was impressed with the wealth and prosperity he noticed in the latter, where even “the boot blacks wore top hats”. He also commented that on the way to the Cape the ship had called in at St Helena to take on coal but that he had been disappointed not to be able to get ashore there to see where Napoleon had spent his final imprisonment. The letter from South Africa to Ruby is easily the longest of those surviving. He expects that his sister will be surprised that he has written so much but explains that it is a fine, quiet night and “the fish won’t bite”. He signs off with Christmas and New Year greetings, commenting that the signalman is grumbling about how much writing paper he has been using.

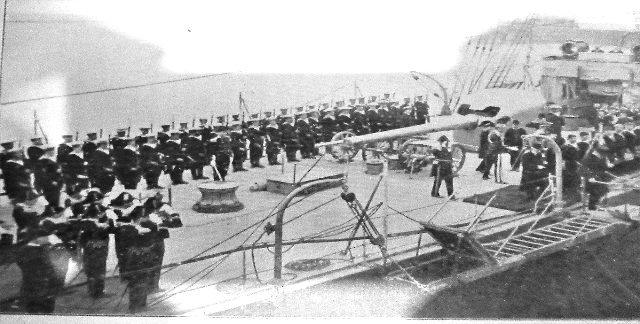

The President of Argentina leaving HMS Glasgow after his visit in 1911 during the ship’s stay in Buenos Aires mentioned in one of Leach’s letters [from “Reminiscences of HMS Glasgow”]

Leach left HMS Glasgow in September 1912 and spent the next months at land-based training establishments, mainly at Good Hope, the Navy’s gunnery school at Portsmouth. By this time, his family had moved yet again, this time to a house in Kenilworth Road, Kilburn. There is one surviving letter from this period of his career which indicates that Tom was hoping to encourage his mother to make another house move. His comments make clear that his sisters Ruby and Elsie had been on holiday to the area and had taken several opportunities to meet him. They had been discussing the future because Leach suggests to his mother that she should consider moving from London to the Portsmouth area, saying he would pay her rent and otherwise keep her so that she no longer had to work. He argued that Elsie liked the area very much and that it would suit him well as he would “have a home here, a thing that I have not had yet in all the years I have been here”. As a final plea he tells his mother “ I should like you to do this very much” and asks for her response. At this stage of his career it is probable that Leach was looking forward to more permanence in the area and was anticipating his departure from the Navy. Of course, neither Leach nor his mother could foresee the events of the following Summer in 1914 when any plans for stability were wrecked. We do not have details of his Mother’s thoughts on his proposal, but certainly no move from London was made and in the Autumn of 1913 Leach was on the move again with two brief postings before his fateful move to the Hampshire in January 1914.

HMS Hampshire photographed soon after her launch in 1903

Hampshire had been transferred to the so-called China Station in 1912 and she was there, in the British leased territory of Wei Hai Wei, when war broke out in August 1914. There are two letters in the collection addressed from this station. The first one, written probably in the Summer, just before the start of the war, contains a mixture of points, probably because as he admitted, Leach had not written for a good while. He complains of the monotony of constant gunnery and torpedo practices but notes they are expecting to sail to Japan in the near future. His expectation at that stage was that they would be away for a further three years, certainly dashing any previous plans for setting up the family in Portsmouth. In a brief reference to the pre-war turmoil at home, Leach supposes that “the Home Rule and Suffragette excitement is still going on”. He has heard a rumour that Home Rule was actually being effected but thought “it would not make any difference to us anyhow”. Of more immediate concern to him was the need for a banjo tutor book and some new strings which he asked his sister Ruby to buy for him and send them on. The second letter was written while at sea off the China coast. A reference in the letter makes clear that the war had started but Leach had had no recent news as to what was going on. His ship had been to Vladivostok and then to Japan where he enjoyed two days’ leave but he warns his mother that there will now be fewer opportunities to write, a suggestion that the realisation was dawning that the war would greatly change all established routines.

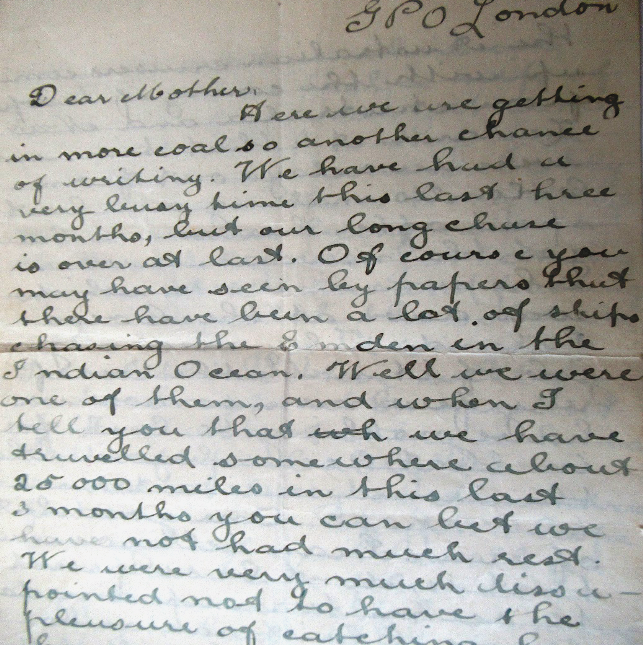

All the remaining letters are war-time correspondence written in the period from September 1914 to June 1916. As such, all mail became subject to strict censorship so as not to impart any potentially useful information to the enemy. As Leach tells his mother in a letter of September 1914, “ I can’t tell you anything as we are forbidden in case of letters getting into enemy hands”. He was able to report that he had received his banjo tutor book but was disappointed to find it was the same one he already had, published about 20 years previously. In his next letter, written in early October, Leach reports that they had done ”another 2000 miles chasing” and were about to put to sea, after coaling, to do more. At this stage, Hampshire had been ordered to search for the German light cruiser SMS Emden which had begun inflicting considerable damage on allied merchant shipping in the Indian Ocean. Later in the month Leach wrote to his sister Ruby giving an update on their mission. Chasing the Emden had continued; according to Leach “ I must not mention where we have been but roughly we have been pretty well all round the China Sea, Pacific Ocean, Straits Settlement and Indian Ocean”. The frustration that he and his ship-mates were feeling at not catching up with the Emden was obvious: the enemy “seems to have a magic way of avoiding us”. Frequent calls to action stations had all resulted in false alarms but he remained confident that Hampshire would catch their prey eventually. On a less cheerful note, Leach reported that one of his former mess-mates had been killed serving in HMS Kennet, a destroyer of the China Squadron which had been damaged in an engagement with German ships off the port at Tsingtao.

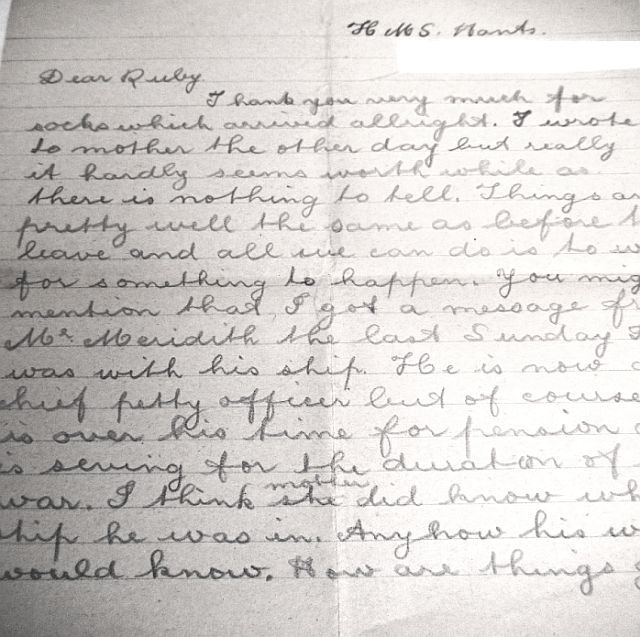

A letter from Leach with the date removed by the censor

By the time he wrote the next letter that can be dated with reasonable accuracy, to his mother this time, the Emden had met its fate. Leach was able now to talk freely about it because the story had been widely reported in the British press. The Hampshire had been chasing the Emden after she was reported to be in the Cocos Islands but the Australian Cruiser Sydney caught up with her first and so seriously damaged her that she was run aground to avoid sinking and then abandoned. Leach and his colleagues were disappointed not to have been the ones to have caught Emden and he was worried that there would be no exciting work for them to undertake besides the patrolling and blockading which he found rather monotonous. This letter was probably written in early December 1914 as Leach also mentions how upset the crew were to receive news of the loss of HMS Bulwark. The Bulwark, a pre-Dreadnought battleship, assigned to escort duty for the British Expeditionary Force to France, suffered a massive internal explosion and sank with loss of over 700 men on 26 November. In the same letter Leach noted the irregular nature of the mail system for the ship, stating that he had only just received his copy of the News of the World newspaper for 4 October sent by his mother!

Only two other letters in the collection are dated. Both were written in March 1915, one to his mother and one to his sister Ruby. At Christmas 1914 a small gift box had been sent to all servicemen on behalf of Princess Mary, although for obvious reasons the gifts were delayed reaching service personnel at sea. Leach tells his mother that he is writing the letter with the pencil which formed part of the gift. Also, he says that he is sending the gift box home for his mother to keep in case it gets lost or damaged on the ship. The crew had also been receiving presents from England of blankets, socks , scarves and the like gathered in national and local appeals on behalf of the Services.

One of Leach’s wartime letters referring to the capture of the Emden

Clearly there was not something for everyone, so the crew organised a lottery with gifts as prizes. Leach received a blanket which he was glad to win as he had been about to buy an extra one following a bout of severe weather. He was less pleased with another development, namely an early “buddy” scheme whereby volunteers at home agreed to write letters to the ship’ crew. Leach considered this an intrusion “that makes lots of people think they have a right to interfere in the private life of others”. He went on to compare the meddling, as he saw it, to a trend before the war of having “the country run by Labour leaders and teetotal fanatics”. Two days later he wrote to Ruby concentrating on far more homely matters. He is looking forward to receiving the socks she has promised to knit as his wear out very quickly and asks if she could get him some sheet music to play on his banjo.

Khaki Cup FinalAll other letters in the collection are undated, in a few cases no doubt because Leach, in his hurry to not to miss the latest mail dead-line, forgot to put a date but mainly because naval censorship tightened as secrecy was deemed vital as the war continued. In one instance the date had obviously been cut out by the censor when Leach had inadvertently added a date. It is virtually impossible to place these letters into a chronological sequence with any certainty, although most are sure to have been sent in 1915. Moreover, generally the content of the letters is mundane and somewhat repetitive and so could have been written at any time in the period December 1914 to May 1916. In some letters, however, references in the content give a clue to approximate time of dispatch. In a letter to his sister Nell, for instance, Leach mentions the Cup Final which “I suppose Charlie would like to see Chelsea win”; they had not heard for certain but there was a rumour on board that Chelsea had lost. The rumour was true, as Chelsea lost the so-called ‘Khaki Cup Final’ to Sheffield United. The game was played at Old Trafford on April 24th , 1915 so that letter can be dated to the late Spring or early Summer of that year. Elsewhere in the letter Leach speculates about the future and his hopes of leaving the service. He wrote “with luck about two years now should finish me. I think we should have finished our business with the Germans by then”. He went on to complain that the Germans were not emerging from their harbours to give battle thus prolonging the monotony of the blockade. A letter to Ruby must have been written at about the same time as he again mentions that he would like to leave the Navy in two years and he asks her to keep an eye open for a suitable job opportunity although” something with not too much work please”!

Khaki Cup FinalAll other letters in the collection are undated, in a few cases no doubt because Leach, in his hurry to not to miss the latest mail dead-line, forgot to put a date but mainly because naval censorship tightened as secrecy was deemed vital as the war continued. In one instance the date had obviously been cut out by the censor when Leach had inadvertently added a date. It is virtually impossible to place these letters into a chronological sequence with any certainty, although most are sure to have been sent in 1915. Moreover, generally the content of the letters is mundane and somewhat repetitive and so could have been written at any time in the period December 1914 to May 1916. In some letters, however, references in the content give a clue to approximate time of dispatch. In a letter to his sister Nell, for instance, Leach mentions the Cup Final which “I suppose Charlie would like to see Chelsea win”; they had not heard for certain but there was a rumour on board that Chelsea had lost. The rumour was true, as Chelsea lost the so-called ‘Khaki Cup Final’ to Sheffield United. The game was played at Old Trafford on April 24th , 1915 so that letter can be dated to the late Spring or early Summer of that year. Elsewhere in the letter Leach speculates about the future and his hopes of leaving the service. He wrote “with luck about two years now should finish me. I think we should have finished our business with the Germans by then”. He went on to complain that the Germans were not emerging from their harbours to give battle thus prolonging the monotony of the blockade. A letter to Ruby must have been written at about the same time as he again mentions that he would like to leave the Navy in two years and he asks her to keep an eye open for a suitable job opportunity although” something with not too much work please”!

Just as families at home were worried about their loved ones on active service, so service personnel were concerned about the welfare of their families as the war progressed. From January 1915 a new worry arose from the start of air raids by Zeppelins, particularly over London. Five letters in the collection refer to air raids dating them to that year, especially as they started to increase significantly from the early Spring of 1915. Leach’s concern was obviously increased by descriptions of the raids and their effects which he had received from Ruby as well as from the newspapers, but he could only give general advice to his mother, writing “try not to worry yourself and try to keep in the lower part of the house if there is any danger”.

A Princess Mary Box like the one Leach received and sent home to his mother. One of the letters was written with the pencil that was among the gifts in the box [© E. Riding Museum]

Just as families at home were worried about their loved ones on active service, so service personnel were concerned about the welfare of their families as the war progressed. From January 1915 a new worry arose from the start of air raids by Zeppelins, particularly over London. Five letters in the collection refer to air raids dating them to that year, especially as they started to increase significantly from the early Spring of 1915. Leach’s concern was obviously increased by descriptions of the raids and their effects which he had received from Ruby as well as from the newspapers, but he could only give general advice to his mother, writing “try not to worry yourself and try to keep in the lower part of the house if there is any danger”.

Apart from censorship, a further constraint on the family’s correspondence was a clearly felt need to try to maintain each other’s morale in difficult times by a adopting a cheerful tone in the letters with an absence of grumbling about conditions imposed by the war. More than once in the letters, Leach, when making a making a muted complaint about some aspect of current life, explicitly states “this is not a grumble”, presumably in order not to upset or worry his mother or sister. A typical example was when he expressed the wish that his mother could instruct the ship’s cooks “how not spoil good food” explaining that “they still make a roast dinner by boiling it on top of the fire first and then ‘browning it off’ with a red hot shovel applied to the topside”. He went on to note that “the only improvement since I joined is that they keep the shovel cleaner”! Generally, however, there is a stress in most letters that he was keeping well and in a much-used phrase “going on all right”.

The Royal Naval Memorial at Portsmouth where Tom Leach and his colleagues are commemorated

No letters in the collection suggest by their content that they were written just prior to the tragic events of June 6th, 1916. Nor has the communication from the admiralty, sent to the Kenilworth Road address in Kilburn informing his mother of his death survived. The devastation caused to his mother and sisters can only be imagined. The bodies of some of the seamen were found later but Leach was not among them. Leach’s death and that of virtually the whole ship’s company were eventually commemorated by a memorial on Orkney and on the Naval Memorial monument at Portsmouth. A more personal memorial to him and his naval career is formed by the letter collection discussed in this article and still preserved and treasured by his family’s descendants.

Further reading:

By Geoff Higgins

The Final Voyage of HMS Hampshire Concert Version: