Up to the age of 12, I had a happy childhood. My father, Henry Angus Milne, known as Harry, was the manager of the Leicester branch of Rayner & Keeler* dispensing opticians. My mother, Ethel, was a full-time housewife, which was conventional in those days.

Rosemary Taylor (née Milne)

When I was 11, I passed the scholarship exam, which meant I could go to one of the girls’ secondary schools in Leicester (later called grammar schools). My parents chose The Newarke School which had recently moved to new premises. Like many girls’ schools then The Newarke had an all female staff. I started there in September 1939 when the war had just begun and for the first term we shared our premises with a city-centre school while their cellars were strengthened to make air raid shelters. Our shelters were built on and partly under one of the hockey pitches and we had an extra week’s holiday while this was done.

Newarke Girls’ Grammar School

I was happily settled at school, but things were not so good at home. First my father, then my mother died of tuberculosis, which in those days was incurable. After my father died, my mother sold her house and we moved to a flat close to the school. While my mother was in the sanatorium, a specialist hospital for TB, I was cared for by Aunt Mary, my father’s sister. Willing to help, she was a dour Scottish lady who was single and called upon for any family emergency; she normally worked as housekeeper/companion to a school headmistress. There was no doubt much family discussion, but the result was that I was adopted by my father’s brother, Uncle Charlie, and his wife, Auntie Connie. They lived in Flixton, near Manchester, and therefore I moved from The Newarke to Urmston school in 1941. The staff at Urmston were mixed, but all the science staff (with the possible exception of Biology) were male.

Urmston Grammar School and a more modern photo showing how little it has changed.

Auntie Connie had once lived in Marple and she had a yearning to return there. As I approached my School Certificate year she began house hunting and found one she liked in Hague Bar. I therefore had to leave Urmston. Auntie Connie had left school at 14 and thought that I had already had plenty of education, but the choice of leaving school or transferring to New Mills VIth form was left to me. I didn’t fancy changing schools again so I left with a good School Certificate.

With hindsight, that was a mistake.

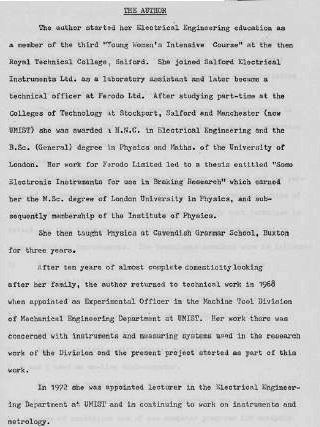

I had read in a “Schoolgirls’ Diary” that there were short courses for girls in science subjects and my main interest was chemistry, but the chemistry course was at Cambridge and I had only just got settled at home. Further enquiries took me to the third “Young Women’s Intensive” course in Electrical Engineering at the Royal Technical College, Salford. Immediately after the end of the war many men were still in uniform and these specialised courses to encourage women to take up careers in science was a response to industry pressure to train alternative staff.

Salford Tech circa 1944 (?)

This led to a job at the Stockport branch of Salford Electrical Instruments** as a “laboratory assistant” which is the lowest form of life in the department. All the companies I worked for allowed one day per week study at a technical college. There was already one woman, Kathie Brett, on the lab staff. I enjoyed working there but after about a year, the lab was moved to the main works at Salford, which was a journey of walk, train, walk or tram and bus, so I started looking for another job.

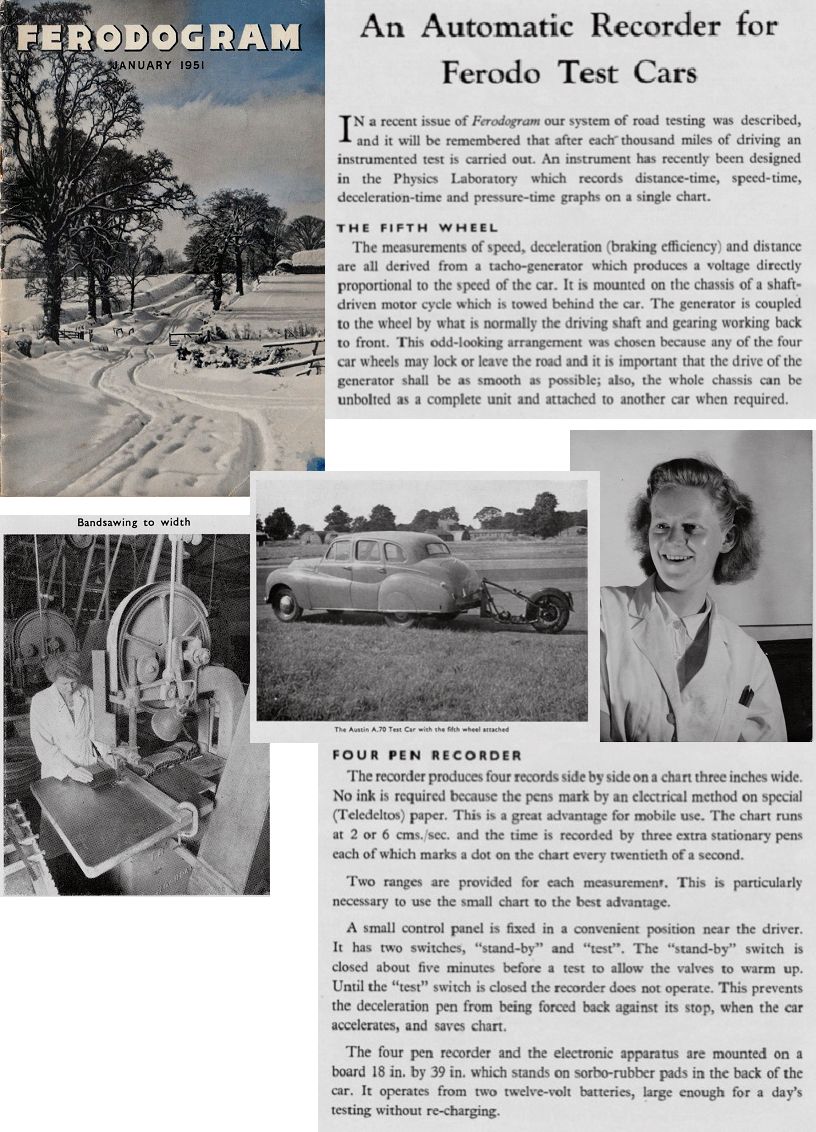

I enquired at Ferodo Ltd, the brake lining manufacturer at Chapel-en-le-Frith, but they had no vacancies. I was more successful at CPA (Calico Printers Association) head office and lab in Manchester and worked there happily for about six months. Then, as their electronics man was leaving, Ferodo contacted me. I moved there and stayed for seven years. I was the only female lab assistant in the Physics lab but there was one, May Heath, in the Chemistry lab. We hardly ever met as the Physics and Chemistry labs were at opposite ends of the works. Ferodo also supported the policy of “day release” which gives staff one day a week during term time to attend Technical College. Some evening courses were usually required as well. Nevertheless, this system allowed, and helped, people like me who had not gone to university straight from school to graduate with a London external degree. In the subjects I studied the staff at Salford Tech were all male, except Miss Brenda Yates, one of the best lecturers I had. She was impeccably neat both in writing and appearance; I’m sure that she was well respected by her colleagues and I would have liked to have known her personally. She had no problems lecturing to a mostly male class.

Ferodo Factory, Chapel-en-le-Frith 1951

After getting my BSc in physics and maths in the early 1950s, I wrote up the work I had done for Ferodo and submitted it for a London external MSc in Electrical Engineering in1952.

I had enjoyed my time at Ferodo, but in anticipation of getting married in 1955 I left to change to teaching physics at Cavendish Grammar School in Buxton***. As I said at the time, I had no illusions that teaching was easier or had shorter hours than industry (although longer holidays), but I felt an early finish and evening preparation fitted married life better than industrial hours.

Cavendish School, Buxton

Then I saw an advertisement (I think in the Guardian) for an “Experimental Officer” at UMIST. Further enquiries showed that it was the sort of opportunity I was looking for and I applied and got the job. At the same time my husband Geoffrey, who was a joiner by trade, but could turn his hand to other building skills, got planning permission for an extension to our bungalow and he decided to leave his employer (Swindells of New Mills) and do the work himself.

For the next few years I was working full-time in Manchester and Geoffrey was working on the house. For the wife to be the breadwinner was an unusual arrangement at that time. He added another storey, gaining two bedrooms and converting it from a bungalow to a house. While he was working at home, he could supervise the children until I came home from work. As well as looking after Joyce and Catherine after school he cooked the dinners every weekday so there was a meal at 6 exactly when I got in. He began with having exact instructions on what and how to cook and ended being very confident within a strictly traditional English menu. As the work on our house neared completion, he had enough requests from friends and neighbours to set up as a self-employed joiner and this became his business for the next twenty-five years.

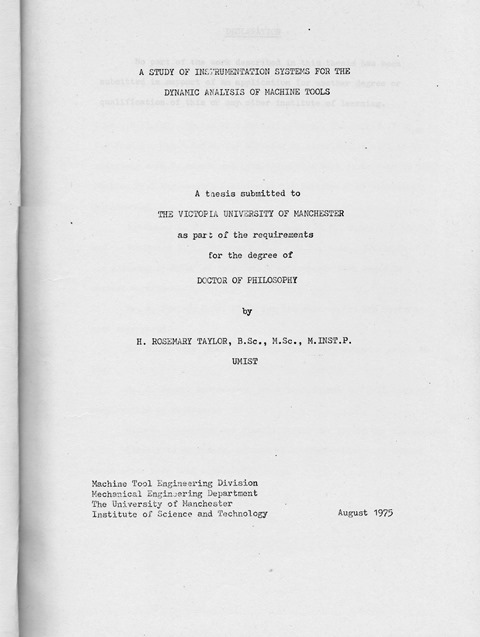

At UMIST I was based in the machine tool section of the department of Mechanical Engineering. A lot of the measurements made in the mechanical section were made with electronic instruments and my job was to look at the detailed specifications of various possible instrumentation and measuring systems and make recommendations for purchase. This work became the foundation of the research that I presented seven years later for my PhD.

In 1972 I was appointed as Lecturer in UMIST’s Electrical Engineering Department. As a lecturer I had to write and deliver lectures at least once a week to large groups of students and was in charge of the project work of several postgraduate students. My specific expertise was instrumentation for precision measuring,mainly of movement, vibration or temperature. UMIST had a lot of overseas students and many I worked with had Chinese origins. I discovered an unexpected liking for Chinese food through being taken out for authentic meals in Manchester. The group photo was taken after a visit with my MSc students to the Derbyshire firm of Land Pyrometers (a pyrometer is a temperature measuring instrument). I was involved in some early efforts towards voice-recognition but it didn’t progress.

During the years at UMIST I was working towards my PhD thesis whichwas on a comparison of several different and alternative precision methods of measuring the same thing. I was comparing some analog methods with digital methods using new computer programs and analysis. Computers were just coming in at this time – the first computer I used was in a six-foot rack. I had to write most of the programs being used. Much of this work was done working late into many evenings after a day's work in Manchester, and after doing baking to keep the homemade puddings and cake supplies going. In 1975 I achieved my PhD and became Dr Rosemary Taylor.

I made my own PhD graduation gown. I felt that doing this was a was a symbol of who I was - a woman able to gain a scientific PhD in middle life, and a woman able to make a complicated precision formal garment. The gown had to have exact numbers of gathers in precisely the right place.

After I got my PhD, I was invited to lecture in South Africa through an established exchange scheme between UMIST and Cape Town University. Geoffrey came with me. At the hotel reception Dr Taylor was assumed to be Geoffrey and he was proud to explain that it was his wife who had that title.

|

|

PhD Thesis "A study of instrumentation systems for the dynamic analysis of machine tools"

Published text book “Data Acquisition for Sensor Systems”: Chapman & Hall

Retirement was automatic at 60, but I took advantage of a scheme that allowed another 3 years of part-time work until 63 and then retired. At 63 I still felt capable of working and enjoyed it and I would have carried on for a few more years if I had the choice. I felt that retirement was leaving a job I enjoyed and got paid for, in order to do housework, a job I didn't like and didn't get paid for. What I did continue to do was voluntary work for Talking Books, which was an organisation providing specially made reel-to-reel tape recorders for the visually impaired. Extra-long tapes played whole books. I was the available local person for any blind person who found their equipment was not working properly and needed it fixed and I enjoyed using my technical skills in this way to help visually-impaired people have access to books. I continued to do this after retirement until the job disappeared with the change from reel-to-reel to cassette tapes.

Looking back on my working life, I see it not as a planned careers but more a series of happy accidents. I could never have said when I was 25 what would happen to my career over the next forty years, but there has been a consistent thread of interest in electrical engineering and electronics and science in general.

Now, thirty years on, I do my best to stay up to date with developments and am still a member of the Institute of Physics and IEE, although I am dismayed to find that my early knowledge of computers has been superseded by developments and everyday usage. Now my grandchildren teach me.

Writing these memories prompted Rosemary to write a poem:

Stay past 90? Life’s not half done make it 91

There’s a lot to do; change that to 92

Or, better, still, see 93

I’d really like to get to 94

And, if I can, stay on till 95

Lord, you know all the tricks, could you manage 96?

And if I’m on my way to Heaven, let me in at 97?

All my life I turned up late, so I’ll arrive at 98

What would really suit me fine – to live to 99.

Chronology

- 1944 - Left school.

- 1944 - Salford Tech

- 1945 - Salford Electrical Instruments

- 1948 - Ferodo

- 1952 - B.Sc. (London)

- 1954 - M.Sc (London)

- 1955 - Qualified as a teacher, ONC (Ordinary National Certificate), HNC (Higher National Certificate), Married Geoffrey Taylor, a native of Strines. Began teaching Physics at Cavendish School, Buxton

- 1957 - Easter: left Cavendish School. Catherine, born in July

- 1961 - Joyce born in December.

- 1968 - Exp. Officer, UMIST - Mechanical Engineering Dept

- 1972 - Lecturer - Electrical Engineering Dept.

- 1975 - M.I.E.E. Member Institute Electrical Engineers C.Eng. Chartered Engineer

- 1975 - Awarded PhD

- 1975 - Published text book “Data Acquisition for Sensor Systems”: Chapman & Hall

- 1987 - Retired [Retirement was automatic at 60, but advantage taken, though, of a scheme that allowed another 3 years of part-time work until 63 and then retired]

- 1990 - Final Retirement

Editors Notes

* The company RAYNER & KEELER LTD, is a Wholesaler, founded in 1910 , which operates in the Import-export - precision instruments industry. It also operates in the and Import- export - medical and surgical equipment industries. It is based in Chesham, United Kingdom. See sketch of original shop.

** On 8 November 1910 the erstwhile meter department of GEC was incorporated as Salford Electrical Instruments Ltd at Peel Works, Silk Street, Salford, Lancs, UK.

During WWII the company contributed to radar development and manufactured proximity fuses. The company produced a wide range of electronic components, transistors, thermostatic devices and measuring instruments. Following a floor collapse at the Silk Street works, production moved to Barton Labs in Eccles, but this facility closed in the early 1980s. See product one and two.

*** For nearly 300 years, Buxton had segregated comprehensive schools. The boys went to Buxton College on College Road, now the co-educational Community School. No longer required, the girl’s school was flattened in the 1990s and swiftly replaced by a housing estate.