Rochdale Visit: 28th February 2013

Rather unfairly, Rochdale is often regarded as being a bit of a backwater. We drive past it on the motorway but don’t think of visiting it. Perhaps that’s why Judith planned an outing there as she had never been to Rochdale either.

Everybody knows Gracie Fields came from Rochdale and, more recently, so did Cyril Smith. However, did you know that John Bright (Anti-Corn Law League) was also born there and, for the real nerds, Lord Byron (mad, bad and dangerous to know) had the full title of Baron Byron of Rochdale. Now that is someone the good burghers of Rochdale would rather not acknowledge. Not at all respectable.

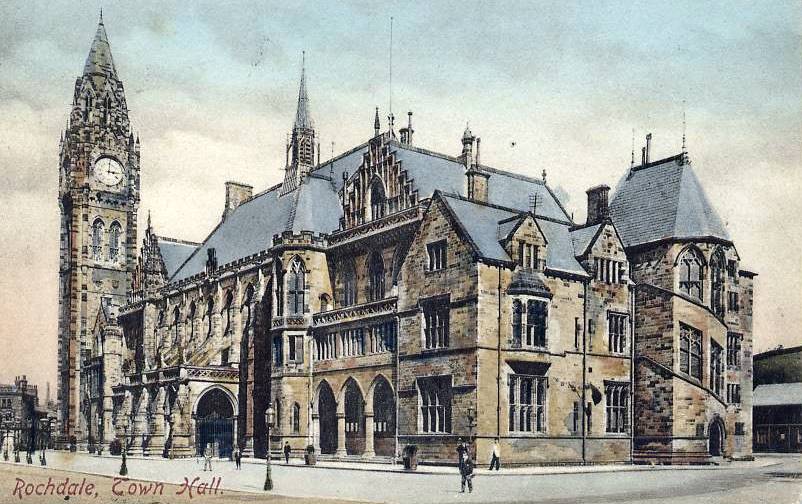

These same good burghers were engaged in something of an arms race in the mid nineteenth century. In  1856, Rochdale was incorporated as a municipal borough and it now had the power to borrow money as well as levy local taxes. Like many other towns in the textile areas of Lancashire and Yorkshire, Rochdale was becoming wealthy and was determined to show this to the world. Leeds had set the example in 1858 with a much-admired Town Hall and many other towns had followed suit. Manchester was even talking about a replacement town hall because the first was too small and not prestigious enough. However, it was Halifax, Rochdale’s near neighbour, that sparked action. Their town hall was opened by the Prince of Wales in 1863. “If ‘Alifax can do it, I’m damned if we can’t do better.”

1856, Rochdale was incorporated as a municipal borough and it now had the power to borrow money as well as levy local taxes. Like many other towns in the textile areas of Lancashire and Yorkshire, Rochdale was becoming wealthy and was determined to show this to the world. Leeds had set the example in 1858 with a much-admired Town Hall and many other towns had followed suit. Manchester was even talking about a replacement town hall because the first was too small and not prestigious enough. However, it was Halifax, Rochdale’s near neighbour, that sparked action. Their town hall was opened by the Prince of Wales in 1863. “If ‘Alifax can do it, I’m damned if we can’t do better.”

It was all agreed and £20,000 was allocated for the building, reduced from £25,000 by some penny-pinching councillors. Five years later the building was opened by the mayor in a very low key ceremony because costs had overrun somewhat - the final bill was £160,000, eight times over budget. However, they did have a very nice building.

The entrance hall was originally used as a wool exchange and is completely floored with Minton tiles. Next door, in the former council chamber, murals depict the inventions that drove the industrial revolution and we were pleased to see that our own William Radcliffe featured prominently alongside such worthies as Richard Arkwright and Samuel Crompton. The Grand Staircase was a fitting introduction to the Great Hall with eleven stained glass windows flooding the stairs with light.

The Great Hall itself was even more imposing with its hammerbeam roof and painted ceiling panels, lit by more stained glass windows commemorating every king and queen from 1066 to Queen Victoria. Three of the panels were being restored by a lady on top of a 30 foot scaffold and it certainly made a difference. After 140 years of dust and grime they looked clean and bright but the three panels had cost £5000. With well over 200 more panels to clean the process could take a long time.

Somehow the words “Rochdale Town Hall” and “Bistro” don’t go together but that was where we had our lunch. It’s true the ambience did not resemble an establishment on the left bank of the Seine but the food was excellent and very good value for money. You wouldn’t get soup and a sandwich for £3.10 in Montmartre and as for a bacon barm for £1.40!

Then off to see where the Co-op movement began. We had hoped to go via Molesworth Street where Our Gracie was born over a chip shop but it was not to be. In any case it is now the site of a car wash so it didn’t really matter. Our destination very nearly met the same fate because Rochdale Council drove a dual carriageway through it in the 1970s but, presumably by accident, they missed the shop where the Rochdale Pioneers started life. The address should really be “t’Owd Lane” but because of the inability of mapmakers to understand the Lancashire dialect it is now forever “Toad Lane.”

The Rochdale Pioneers was not the first co-operative - there were several hundred before 1844 - but it was the first successful one and it became the model for most co-operatives to follow. They studied previous attempts at co-operation and tried to draw up guidelines of good practice -

the Rochdale Principles.

Open membership.

Democratic control (one person, one vote).

Distribution of surplus in proportion to trade.

Payment of limited interest on capital.

Political and religious neutrality.

Cash trading (no credit extended)

The shop began by selling four basic necessities - butter, sugar, flour and oatmeal - unadulterated and reasonably priced. The concept was an instant success; the range expanded rapidly, membership soared and the idea was taken up in many other localities. Within ten years there were over 1000 co-operatives in Britain and the idea had spread to many other countries.

The museum was fascinating with its range of exhibits which took many of us down memory lane - delivery bicycles, old-fashioned packages, advertising from a bygone age. We will be well prepared for the talk in September about the history of the co-operative movement. An interesting and very enjoyable day, thanks to Judith. Only one complaint - we didn’t get our divi!

Neil Mullineux

Photos 1 & 3 of the 4, reading down by kind permission of Arthur M. Procter

Further Resources:

Rochdale Town Hall

On Wikipedia.....click

Possible future of the Town Hall....click

How the Town Hall may have looked,after German Invasion....click

Co-Op History

Rochdale Pioneers Museum.....click

The Co-operartive/our history....click

Rochdale Pioneers on youtube....click