Let them eat cake! That’s the way to do it! To ensure that the members of the Society come along on a balmy spring evening to the drudgery of an AGM, bribe them with a cuppa and a cake ‘tween AGM and the talk. The committee are mandated to provide the cake, is there no end to their responsibilities? That evening though, unbeknown to them, there was a further treat; not one, but two talks from Kevin Dranfield. Though originally scheduled to give us a talk on the Marple Fly Boat, Kevin generously threw in a freebie, a talk on the Marple Tramway.

Marple Fly Boat, a canal development, came from a railway shortcoming, Marple Tramway a ‘railway’ development from a canal shortcoming. Both were short lived, dew in the early morning of the Industrial Revolution day.

Though we normally think of the development of railways following that of canals, in this instance the tramway came earlier than the fly boat. The Marple fly boat ran from 1842-62, whilst the earlier tramway was in operation from 1798 to 1807. A fly boat (packet boat) was an express canal boat, a tramway also known as a wagonway, consisted of horses, other equipment and tracks for guiding wagons.

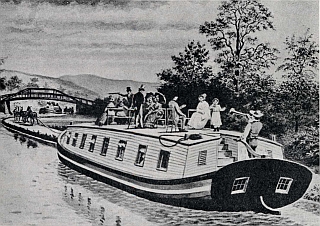

The Glasgow and Paisley canal can lay claim to have had the first fly boat. A fly boat service that was hit by the worst canal accident in the country, when in November 1810, 85 people were killed when the Countess of Eglinton capsized. Fly boats were 70 feet long, 6 feet wide, pulled by two horses or more, carrying 100 to 150 people at ten miles per hour, a challenge to the stage coaches of time running on turnpikes. They were the only canal boats to be painted white, allowing them to run at night, and had a blade mounted at the front to cut any tow ropes that came in their way.

The greatest user of fly boats in the north-west England, was the Lancaster and Kendal Canal. In 1842 an entrepreneur from Ashton, spotting an opportunity,  brought fly boats down from Glasgow, the mode of transport unknown, for this long journey. These became the Marple Fly Boats, running the seven miles from Dog Lane Station, near Dukinfield, to Bottom Lock in Marple. This journey was adjourned at several pubs on the way; the extent of this delay can be seen from *Joel Wainwright's comment that the fly boat never beat him, though he was on foot, on the journey from Ashton to Marple. Nevertheless, the fly boat was such a success that the Royal Mail had a contract with them for the carriage of mail from Marple. By 1858 the railway had reached Hyde, and the fly boat route was shortened. Four years later, in 1862, the service ceased as the railway reached Compstall. Evidence of the running of the fly boat can still be seen on the canal, walking from Ashton to Marple, look out for a 70 foot + stretch of straight towpath, these were the stopping place for the fly boat.

brought fly boats down from Glasgow, the mode of transport unknown, for this long journey. These became the Marple Fly Boats, running the seven miles from Dog Lane Station, near Dukinfield, to Bottom Lock in Marple. This journey was adjourned at several pubs on the way; the extent of this delay can be seen from *Joel Wainwright's comment that the fly boat never beat him, though he was on foot, on the journey from Ashton to Marple. Nevertheless, the fly boat was such a success that the Royal Mail had a contract with them for the carriage of mail from Marple. By 1858 the railway had reached Hyde, and the fly boat route was shortened. Four years later, in 1862, the service ceased as the railway reached Compstall. Evidence of the running of the fly boat can still be seen on the canal, walking from Ashton to Marple, look out for a 70 foot + stretch of straight towpath, these were the stopping place for the fly boat.

By 1796 the Upper Peak Forest canal construction from Bugsworth to Top Lock, Marple had been finished. The canal had been promoted to convey coal and limestone, used together to produce lime, to Manchester, Samuel Oldknow was instrumental in the effort. The Aqueduct was completed in 1800; the Lower Peak Forest Canal in 1798. The two canals were to be joined by a flight of 16 locks. But no money was left to build these locks at the time, leaving a yawning gap between the two sections of canal, so a way had to be found to connect the two sections of canal. Thus the tramway was born. This ran one and a quarter miles from the Lime Kilns in Marple to the Aqueduct. The tramway, surveyed by Thomas Brown and the consulting engineer and resident engineer were Benjamin Outram and Thomas Brown, respectively, was opened in 1797; by 1803 enough money was found to build the locks, completed by 1805, when the tramway closed, but references to the tramway appeared in 1807.

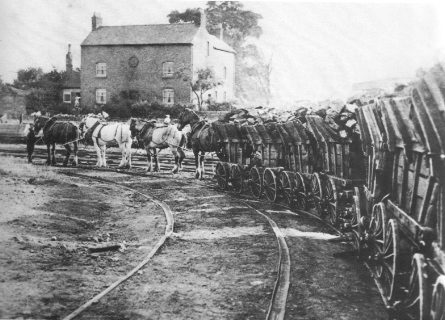

It was in operation 24 hours a day, the level of traffic was such that in 1801 the track was doubled. It consisted of L section rails, the wagons having road, cart wheels. The rails, one yard long, were of cast iron, these lay on stone blocks, with a spike going into an oak insert in the stone. Operation was by gravity down from the Lime Kilns to the Aqueduct, with horses taking the empty wagons back up the incline. The ‘trains’ consisted of a number of wagons, 2 ton capacity, a ganger was in charge, with lads on the wagons, whose job was to brake the train with a hook to put on the spokes, not much Health & Safety then ! On a busy day up to six hundred tons of cargo were moved.

The tramway route, from Oldknow’s Lime Kilns, across the now Recreation Ground, where the line of the embankment can still be seen, from there along what is now St. Martin’s Road, from there dropping down towards Brabyns Brow crossing the locks at Lock 10, were a temporary bridge was built, physical evidence can be seen in notches in the copping stones, and a hole for a spike in a stone block. The tracks then proceeded across Brabyns Brow, and then along the line of what has become Aqueduct Road, terminating at Aqueduct Basin, on the Lower Peak Forest Canal.

A massive thank you to Kevin for bringing the season to an end with such style, an evening thoroughly enjoyed by all, despite the AGM.

Tramway Embankment (L) Recreation Ground and Lock 10: Coping stone notches for temporary bridge

*Joel Wainwright was born in 1831 near Woodley, educated at Stockport Grammar School and became manager of Strine Print works before setting up as an accountant and company director. He was protégée of Joseph Sidebotham of Denton and as a result became part of a circle of amateur naturalists and artists which included Leo Grinden and James Nasmyth (the inventor of the steam hammer) and wrote

Memories of Marple

Pictorial and Descriptive Reminiscences of a Lifetime in Marple

Further Reading: The accident on the Paisley Canal : Paisley Online

Lancaster Canal Packet Boats

Little Eaton Tramway website at Wikipedia

Marple Tramway...on Marple-uk

and Peter Whitehead's Industrial Heritage of Britain site here