Manchester has been termed the ‘Shock City’ of the nineteenth century by Asa Briggs. The population grew exponentially, from 17,000 in 1760 to 180,000in 1830. For centuries the country had been a rural nation, living on the land. But with the coming of industry all that changed. Factories sucked a population in, and exhaled smoke, a foul smog, that filled the air of the growing cities and towns. In the squalid conditions that resulted, political unrest and radicalism flourished, particularly in South Lancashire. By 1819 the one million people in the Manchester and surrounding area were represented by 2 MPs. By comparison more than half of total number of MPs was elected by 154 votes. The cost of food had risen with the passing of the Corn Laws in 1815, wages had fallen. Weavers who could have expected to earn 15 shillings for a six-day week in 1803, saw their wages cut to 5 shillings or even 4s 6d by 1818.

Manchester has been termed the ‘Shock City’ of the nineteenth century by Asa Briggs. The population grew exponentially, from 17,000 in 1760 to 180,000in 1830. For centuries the country had been a rural nation, living on the land. But with the coming of industry all that changed. Factories sucked a population in, and exhaled smoke, a foul smog, that filled the air of the growing cities and towns. In the squalid conditions that resulted, political unrest and radicalism flourished, particularly in South Lancashire. By 1819 the one million people in the Manchester and surrounding area were represented by 2 MPs. By comparison more than half of total number of MPs was elected by 154 votes. The cost of food had risen with the passing of the Corn Laws in 1815, wages had fallen. Weavers who could have expected to earn 15 shillings for a six-day week in 1803, saw their wages cut to 5 shillings or even 4s 6d by 1818.

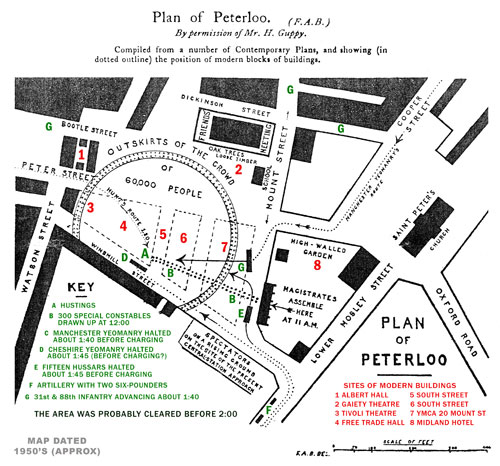

The Manchester Patriotic Union, formed by radicals from the Manchester Observer, organised a ‘great assembly’, on August 19th 1819, to respond to the economic conditions and the need for greater suffrage. Radical orator Henry Hunt was asked to chair the meeting. The magistrates became perturbed by this chain of events, and had over 1,500 soldiers and special constables assembled in Manchester close to the site of the rally, St. Peter’s Field. The day was a hot, and cloudless, as the men, women and children assembled, with dignity and discipline, the majority dressed in their Sunday best and some with picnics. Modern estimates put the crowd at between sixty and eighty thousand. The meeting was intended to be a peaceful affair; Henry Hunt asked that the crowd ‘come armed with no other weapon than that of a self-approving conscience’. The magistrates met in Mr. Buxton’s house, which overlooked St. Peter’s Field, the house is now the the site of the Midland Hotel. Special constables went into the field at about noon to form two lines to keep the passage through the crowd a few feet wide, from the house of the magistrates to the hustings, two carts tied together, to be used by the speakers.

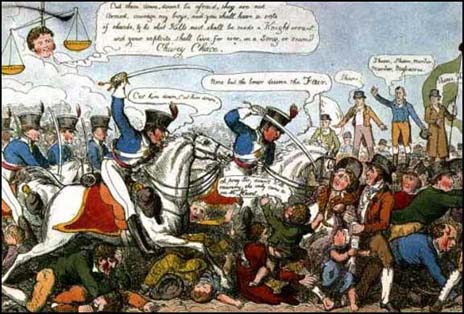

‘Orator’ Hunt arrived at about 1pm., he was joined on the cart by others including, Joseph Johnson, the organizer of the meeting, and a reporter, John Tyas of The Times. William Hulton, the chairman of the magistrates, saw the enthusiastic reception for Hunt’s arrival, and issued an arrest warrant for him and others on the carts. The chief constable, Andrews, was of the opinion that military help would be needed to make arrests. Notes from Hulton were then passed to two horsemen. Major Trafford, who was positioned only a few yards away at Pickford's Yard, was the first to receive the order to arrest the men. Major Trafford chose Captain Hugh Birley, his second-in-command, to carry out the order. Local eyewitnesses claimed that most of the sixty men who Birley led into St. Peter's Field were drunk. Birley later insisted that the troop's erratic behaviour was caused by the horses being afraid of the crowd. The Manchester & Salford Yeomanry drew their swords and galloped towards St. Peters Field. At about 1.40pm they entered the narrow corridor created by the special constables, but the horses were inexperienced and as they got deeper and deeper into the crowed they reared and plunged, the riders began to hack about them with their sabres, trying to clear the by now angry crowd. On arriving at the meeting stand, Hunt and several others including reporter Tyas were arrested. However Hulton having seen what he perceived to be an attack on the Yeomanry, ordered the waiting Hussars, with the words "Good God, Sir, don't you see they are attacking the Yeomanry; disperse the meeting!” under the command of Guy L’Estrange, to disperse the crowd, to do so they charged into it. The crowd were dispersed within ten minutes, but at the cost of 15 dead and more than 600 injured.

This was the first meeting at which journalists were present and, within a few days accounts appeared in newspapers. A feeling of indignation became intense. The event proved the catalyst for the birth of the Manchester Guardian, founded in 1821, to replace the Manchester Observer.

The poet Shelley on hearing of the massacre was moved to write ‘The Masque of Anarchy’.

If, as Wellington claimed the Battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton, then, it could be said that democracy was won on the killing fields of the Peterloo Massacre, St Peter's Field.

Martin Cruickshank - September 2012