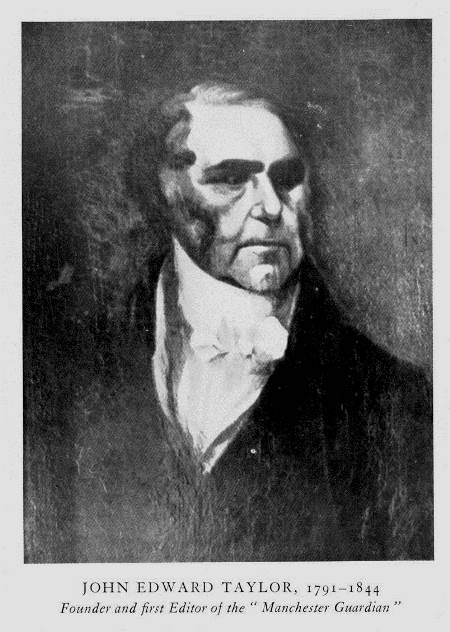

The story of a house, but no ordinary story. Diana Leitch gave us a history that encapsulated much of what Manchester is about - manufacturing, radical politics, global trade and scientific research. It was the tale of two houses on the Towers estate in Didsbury. The first house, S cotscroft, was built by John Leech, the head of the Leech family of millowners from Stalybridge. However, although the family fortune was founded on cotton, he had diversified into engineering and even shipbuilding. It was an impressive house but not as impressive as the house that was built nearby in the 1860s. This was built near Scotscroft for the editor (and owner) of the Manchester Guardian, John Edward Taylor. It was certainly not built on the cheap. It cost £50,000 in 1862, more than £5 million in today’s currency. Standing in 14 acres, Pevsner has described it as “the grandest house in north west England.” However, his praise was not unqualified. He also described it as “grossly picturesque in red brick and red terra cotta.” Unfortunately Martha Taylor, Edward Taylor’s wife, held the same opinion and she refused to live there.

cotscroft, was built by John Leech, the head of the Leech family of millowners from Stalybridge. However, although the family fortune was founded on cotton, he had diversified into engineering and even shipbuilding. It was an impressive house but not as impressive as the house that was built nearby in the 1860s. This was built near Scotscroft for the editor (and owner) of the Manchester Guardian, John Edward Taylor. It was certainly not built on the cheap. It cost £50,000 in 1862, more than £5 million in today’s currency. Standing in 14 acres, Pevsner has described it as “the grandest house in north west England.” However, his praise was not unqualified. He also described it as “grossly picturesque in red brick and red terra cotta.” Unfortunately Martha Taylor, Edward Taylor’s wife, held the same opinion and she refused to live there.

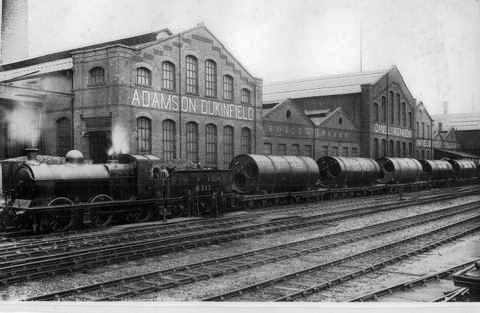

Selected plots on the estate were sold for careful development and James Watts of Abney Hall, built a number of German-style houses, essentially on a whim. The main house was put up for sale and in 1874 it was bought by Daniel Adamson. He was very much a self-made man. Apprenticed to the Stockton and Darlington Railway, he rose to become general manager by the time he was thirty and then moved to Stockport to manage the Heaton Foundry. Soon afterwards he set up his own company and made a fortune manufacturing Manchester boilers. His works in Dukinfield diversified into locomotives and he had interests in a mill building company and a number of iron works throughout northern England.

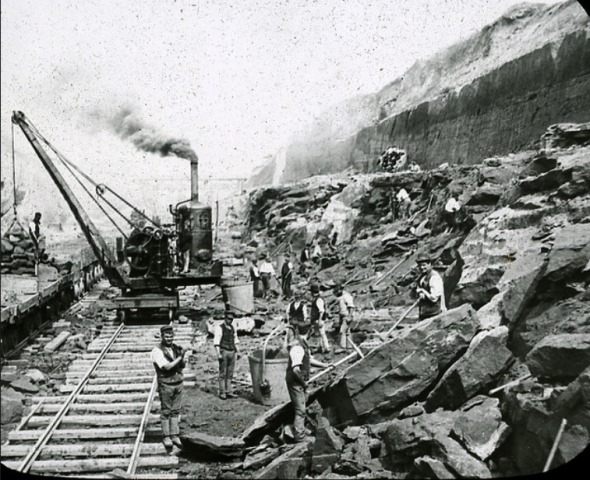

He was a champion of the Manchester Ship Canal project and in 1882 he convened a meeting at The Towers of 68 leaders of commerce, industry and finance as well as influential politicians. They signed a declaration of intent that day and Adamson was elected chairman of the committee responsible for pushing the scheme through in the face of intense opposition. The table where the agreement was signed is now on display at Newton Hall between Hyde and Dukinfield.

He continued in this role when the Act of Parliament was eventually passed, three years later, and he was the first chairman of the Manchester Ship Canal Company. Although he resigned before the actual construction was started because of ill health, he played a key role in setting the standards to which the company would operate. Much of the engineering had never been attempted before and Adamson was instrumental in establishing temporary hospitals for the treatment of the enormous workforce. An average of 12,000 men were employed over the contract, at one point peaking at 17,000. Unfortunately he died in 1890, before the canal was finished, but it was his most important lega cy. His engineering company remained a family company until it was sold to Acrow Engineers in 1964.

cy. His engineering company remained a family company until it was sold to Acrow Engineers in 1964.

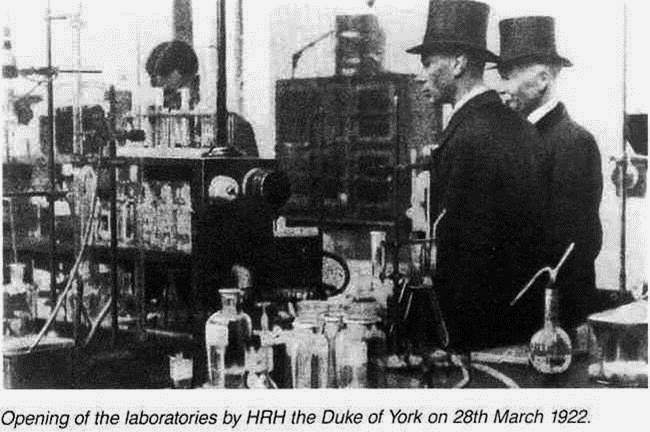

His elder daughter, Alice-Ann, who was married to Joseph Leigh, a Stockport cotton manufacturer, inherited The Towers after her father died but by the time of the First World War the house was given over to the government as a recreation and convalescent home for injured soldiers. It came up for sale in 1920 and was purchased by the British Cotton Industry Research Association. The government and the industry had belatedly accepted that foreign competition often had superior technology and that the cotton industry had to adapt in order to survive. The various cotton trade organisations imposed a levy on their members to fund this institute but William Greenwood, MP for Stockport, donated most of the money for the setting up costs and capital investment. His main condition was that the new institute should be named after his daughter; hence the Shirley Institute was born.

The organisation concentrated on fundamental research and production technology. Over the years it developed ‘Ventile’, a waterproof fabric for outdoor wear and it introduced the ‘tog value’ as an internationally recognised measurement ofthermal insulation. It was welcomed as a more user-frienly alternative to the SI unit of m2K/W. It developed materials for space exploration but perhaps its most useful innovation for the general population was a flea-resistant cat collar.

Despite its achievements, the Shirley Institute was not immune to the troubles of the cotton industry as a whole. As firms closed or amalgamated its funding decreased and its research contracted. In 1961 it merged with the British Rayon Research Association and then in 1987, the ultimate indignity, it merged with the Wool Industry Research Association to form the British Textile Technology Group. It is no longer in The Towers as the house has now given a home to small and growing businesses at the centre of The Towers Business Park. A fitting next chapter to an eventful history.

Despite its achievements, the Shirley Institute was not immune to the troubles of the cotton industry as a whole. As firms closed or amalgamated its funding decreased and its research contracted. In 1961 it merged with the British Rayon Research Association and then in 1987, the ultimate indignity, it merged with the Wool Industry Research Association to form the British Textile Technology Group. It is no longer in The Towers as the house has now given a home to small and growing businesses at the centre of The Towers Business Park. A fitting next chapter to an eventful history.

A fascinating talk from Diana Leitch but she too, represents another part of the Shirley Institute’s legacy. The achievements of the Institute are commemorated at the Catalyst Science Discovery Centre in Widnes. Not the snappiest of titles, which is a pity, as the museum itself is dedicated to making chemistry of all varieties, not just textiles, fascinating to young people. Shirley (Greenwood) would be delighted.

Neil Mullineux - April 2019

Postscript

There is a local connection to the Adamson family. The archivist at All Saints’ has noted that Alice-Ann Leigh, the eldest daughter of Daniel Adamson is buried at All Saints’ beside her husband and three of her children. Joseph Leigh was a prosperous cotton manufacturer in Stockport and soon after their marriage in 1868 they came to live in Marple at Beech House on Station Road. Although they did not stay long, Marple obviously held a place in their hearts as they chose it as their final resting place.