The talk was entitled “Mrs Gaskell and servants” but Anthony began by discussing the servant situation in Marple. This area was not wealthy in the early Victorian era, the time when Mrs Gaskell was making her name as a novelist in her own right as well as the wife and partner of a well-known Unitarian minister. The two ‘Big Houses’ in Marple each had a team of servants, both domestic and estate, though surprisingly Brabyns supported the larger number. Apart from that, few households employed more than one or two domestic helps. As the century progressed and particularly after the railway came to Marple in 1865, more middle class professional people came to value the country air and invariably employed servants to work as cooks and gardeners as well as domestic maids. In that aspect, Marple was typical of many communities in the nineteenth century and we realised that Anthony was using his title as an introduction to the wider world of domestic service in that time.

Although the number varied, the Gaskell household usually employed five servants and they covered a variety of tasks between them, both indoors and outdoors. The concept of paid service had emerged gradually, as in medieval times the practice was for a period of indenture rather than a paid employee. It was only in early modern times that servants as we know them became common, reaching a zenith in late-Victorian times until the outbreak of the First World War.

However, the change in relationship between master and servant led to other difficulties, not the least being the relative hierarchy within the body of servants. This was not usually a problem in the big houses with a large number of servants; they invariably arranged their own hierarchy, either formally or informally. It was rather more of a problem in the emerging middle-class households such as the Gaskells. With only four or five servants, looking after both domestic and estate duties there was ample scope for dissension and ill-feeling. The situation often required the master or, more likely, the mistress, to interve ne and lay down clear guidelines. Moreover, it was not simply a problem that could be settled once and for all. With established servants leaving and new recruits joining, the status quo was often upset and new responsibilities and demarcations had to be established.

ne and lay down clear guidelines. Moreover, it was not simply a problem that could be settled once and for all. With established servants leaving and new recruits joining, the status quo was often upset and new responsibilities and demarcations had to be established.

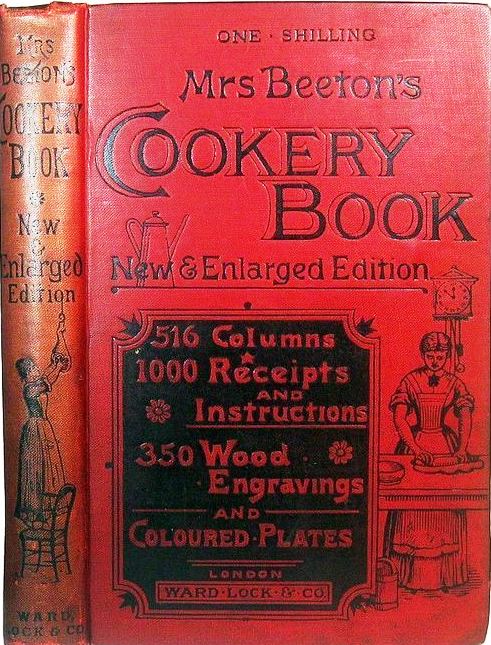

The mistress of the household was often young or completely inexperienced in this role so to give practical help and advice a new type of instruction manual became popular - advice on organising everyday work in suburban villas. Some went into great detail, others just gave general guidelines but they all found a ready market. Mrs Beeton was probably the most well-known of these advice authors and she went into great detail. For the modern reader they show another age. A typical entry* would give not just a list of duties for a housemaid but go on to show a suggested timetable for her day’s work, starting at six o’clock in the morning and describing activities until well into the evening. Unfortunately, despite these books, many ladies found that the theory was not the same as the practice and there are many middle-class diaries bemoaning the difficulty of organising servants.

[*typical entries 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 ]

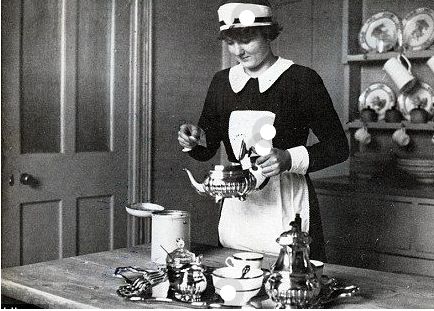

The working conditions for servants in the nineteenth century varied considerably but over time they gradually improved. Most were given board and lodgings so they were able to save despite comparatively low wages. There was strict separation between male and female though in smaller households this could be difficult to achieve. Of course the long hours also meant that there were fewer opportunities to spend money. Although it was rarely explicitly stated, employers did not want servants to have an active social life or perhaps any social life at all. However, many employers expected servants to provide their own clothes and these often required changes in the course of the day, depending upon the work being carried out. And of course, servants were expected to show due respect to their employer. At its extreme in a few of the big houses, some grades of servant were expected to face the wall if they met their employer in the course of their duties. However, this was regarded as of another age in most houses and all that was expected of the servants there was a respectful “Sir” or “Madam” when addressed.

opportunities to spend money. Although it was rarely explicitly stated, employers did not want servants to have an active social life or perhaps any social life at all. However, many employers expected servants to provide their own clothes and these often required changes in the course of the day, depending upon the work being carried out. And of course, servants were expected to show due respect to their employer. At its extreme in a few of the big houses, some grades of servant were expected to face the wall if they met their employer in the course of their duties. However, this was regarded as of another age in most houses and all that was expected of the servants there was a respectful “Sir” or “Madam” when addressed.

This gradually came to an end as various historical trends coalesced. There were more work opportunities outside domestic service, especially for women; advances in technology provided labour-saving devices; and the First World War together with the economic turmoil that followed accelerated the gradual move towards a more egalitarian society. The role of the servant had lasted for centuries but had changed radically in that time and finally came to an end in the middle of the twentieth century, at least in developed economies. An illuminating analysis by Anthony on a little researched subject.