Buxton Crescent

Buxton Crescent

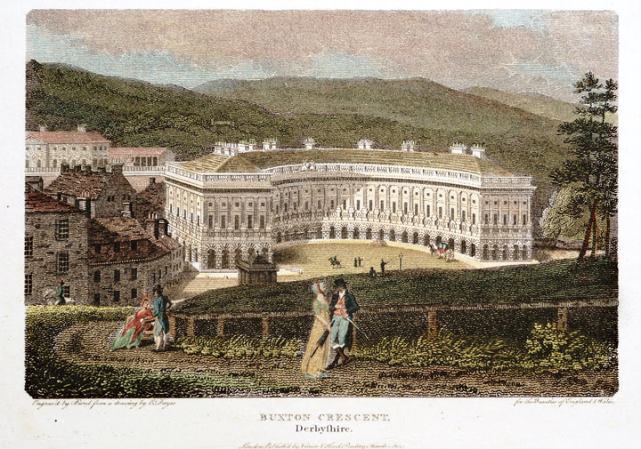

“Buxton Water.” It is the water that is the raison d’être for Buxton. Without the water there would be no Buxton. But there is another feature of the town that is just as iconic - The Crescent, and it was The Crescent that was the subject of Trevor Gilman’s talk in September for the first meeting of the year.

The water is, of course, older than Buxton itself. It first fell as rain about 5000 years ago, slowly filtered through the limestone of the Peak District and eventually emerged as nine separate springs in the vicinity of The Crescent. In the course of this slow migration it absorbed significant amounts of magnesium and about 40 other minor constituents, finishing its journey having been warmed by geothermal activity to about 27oC (82oF) and acquiring a faint blue colour. (It is also slightly radioactive.)

It was the Romans who first put Buxton on the map in AD70 when they established the settlement of Aquae Arnemetiae. Along with Aquae Sulis (Bath) it was one of only two Roman bath towns in Britain. It gradually acquired religious significance throughout the Middle Ages and the main source was dedicated to St Anne after the mother of the Virgin Mary. Although it was closed by Thomas Cromwell in the course of dissolving the monasteries, Mary, Queen of Scots visited during most years of her imprisonment.

5th Duke of Devonshire However, these developments were small scale and it was left to the 5th Duke of Devonshire to develop Buxton into a nationally known spa. Bath had become a fashionable destination in the first half of the eighteenth century, particularly under the influence of Beau Nash, and the Duke decided that the north of England needed an equivalent venue. The Devonshires were wealthy by any standards but in 1760 the Duke had taken over management of the Deep Ecton coppermine in Staffordshire. By investing in the latest technology, including Boulton & Watt pumping engines and winding plant. The mine proved incredibly profitable for thirty years until the main ore pipe ran out, and The Duke used this to finance his property developments in Buxton.

5th Duke of Devonshire However, these developments were small scale and it was left to the 5th Duke of Devonshire to develop Buxton into a nationally known spa. Bath had become a fashionable destination in the first half of the eighteenth century, particularly under the influence of Beau Nash, and the Duke decided that the north of England needed an equivalent venue. The Devonshires were wealthy by any standards but in 1760 the Duke had taken over management of the Deep Ecton coppermine in Staffordshire. By investing in the latest technology, including Boulton & Watt pumping engines and winding plant. The mine proved incredibly profitable for thirty years until the main ore pipe ran out, and The Duke used this to finance his property developments in Buxton.

The Crescent was to be the centrepiece of the development but only a part of a larger vision. By modern standards the development showed little sensitivity to the existing urban environment. Building began in 1780 on a site defined by a bend in the River Wye which had previously been ornamental gardens. These were destroyed, the river itself was culverted, one of the existing springs was blocked and they destroyed a large part of the Roman baths. Sensitive it was not! However, they did redeem themselves to some extent by landscaping St Ann’s Cliff in front of the Crescent.

The design was conceived and carried out by John Carr, the leading architect in the north of England, who regarded this as his finest achievement along with Harewood House in Yorkshire. The Crescent is notable for being an early example of multifunctional architecture. As well as hotels and lodging houses, it contained Assembly Rooms, shops, a post office and a public promenade, all under one roof. This was not necessarily the original intention. Similar developments in Bath such as the Circus and the Royal Crescent were composed almost exclusively of town houses but it would seem that there was not enough of a market in the north to build a complete development of town houses. Instead the Crescent had a hotel at each end and lodging houses between together with public rooms for assembly and an arcade of shops.

The development was certainly a success, patronised by such luminaries as Erasmus Darwin and Josiah Wedgwood, though it never achieved the fashionable status of Bath. Within thirty years of its completion most of the lodging houses had been absorbed into the two hotels. Although the Duke of Devonshire gave up his town house in 1804 the town continued to progress throughout the nineteenth century. The Serpentine Walks were landscaped by Joseph Paxton and the Pavilion itself, a glass and iron structure built in 1871, was very much influenced by him. The Pump Room which faces the Crescent was built in 1894 and the Opera House was completed soon after.

However, the Edwardian era proved to be the apogee for the town. After the First World War it could not retain its lure for an impoverished nation and it gradually faded. The Crescent Hotel continued until 1935 when it became a clinic annexed to the Devonshire Royal Hospital. In the 1970s it was acquired by Derbyshire County Council for use as offices and the town library until it was vacated in 1991. The St Ann’s Hotel continued in use as a private hotel until 1989, its demise hastened by the discovery of rats the previous year, an event that received wide publicity. No sooner had it closed than severe gales caused considerable damage to the roof and exacerbated the very poor state of repair.

Not everything was going downhill. Trevor had lived in Buxton since 1951 and there were occasional attempts to build on the solid heritage of the town. The Playhouse Theatre kept a repertory company and the Opera House reopened in 1979 with the launch of the Buxton Festival. The gardens were given a fresh makeover and the Pavilion was given a variety of roles. The problem was that these isolated improvements were not sufficient, by themselves, to change the overall direction. The central area needed very substantial investment within the context of a plan for the whole area, involving a number of partners. It was slow work with many false starts but gradually things began to coalesce. There was a protracted campaign, initiated by the newly formed Buxton Group to secure direct action by the Department of National Heritage. This resulted in grants totalling £1.5 million to enable repair works to be carried out to The Crescent in 1994-96. Many attempts were made to try to find a suitable developer for the building. Several schemes were put forward, often in conjunction with Nestlé which had bought the rights to Buxton Water and were planning a major commercial investment. It has now finally come to fruition with an 80 room hotel, a mineral water spa and the development of the Pump Room to allow visitors to take the waters. A long, long journey but hopefully Buxton has arrived.

Inside the 2021 Buxton Crescent Health Spa Hotel

Inside the 2021 Buxton Crescent Health Spa Hotel

Despite his comprehensive detailing of the Crescent, Trevor made no mention of Georgiana, the Duke’s wife, and their unusual marital arrangements. This could be because he just didn’t have time or perhaps because it didn’t bear directly on the evening’s main subject. Nevertheless, if Trevor should visit us again, it would certainly be of interest to our members to hear his views on this lady.