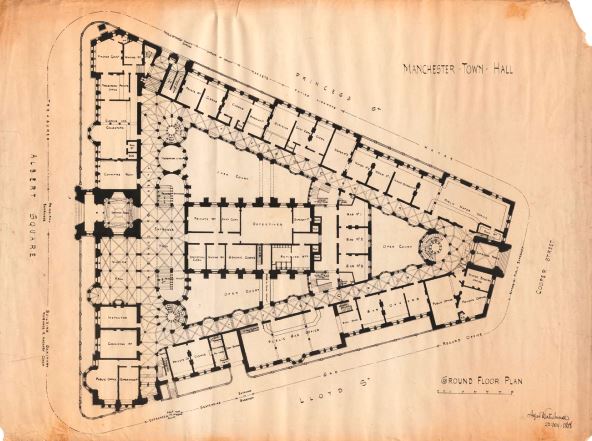

Town Hall Manchester Ground Floor

Town Hall Manchester Ground Floor

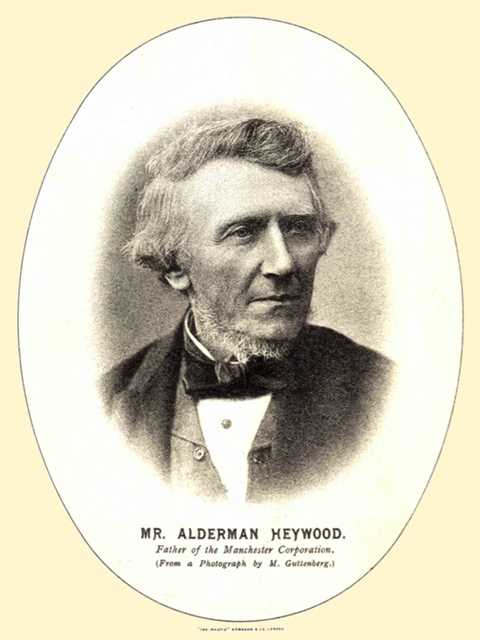

Abel Heywood - Radical Mayor

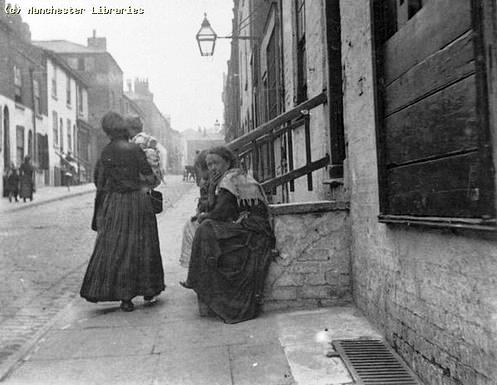

They don’t make mayors like they used to! Joanna Williams took us through the life of one of the most important figures involved in the growth and development of Manchester. Abel Heywood was Manchester through and through; his life paralelled the history of the  Angel Meadows Schoolcity, but it was hardly an auspicious beginning. Born to a poor family in Prestwich, his father died when he was very young and his mother moved to Angel Meadow. We know all about Angel Meadow, thanks to Mike Nevell’s talk on the subject in 2016 and it was certainly not a good start in life for anybody.

Angel Meadows Schoolcity, but it was hardly an auspicious beginning. Born to a poor family in Prestwich, his father died when he was very young and his mother moved to Angel Meadow. We know all about Angel Meadow, thanks to Mike Nevell’s talk on the subject in 2016 and it was certainly not a good start in life for anybody.

Fortunately Abel showed drive and determination from an early age and he began to rise above his surroundings. He obtained a basic education at the local Anglican school but left there at nine to work in a warehouse for 1/6d per week. By the time he was fourteen he was in charge of 60 child workers. He was also an enthusiastic learner and he supplemented his voracious reading by attending the Manchester Mechanics Institute. However, his radicalism showed itself in the differences he had with the trustees of the Institute. He believed strongly that the working class should have a political education but this was anathema to the men that controlled the Institute. He left and set up a penny reading room in Manchester where anyone could read the range of periodicals and newspapers he provided. Linked with this he took on the Manchester agency for the Poor Man’s Guardian, a weekly newspaper which challenged authority. He refused to pay stamp duty on newspapers and at one point he went to prison as well as being subjected to frequent and heavy fines.

Despite these principled travails his business prospered, developing into a bookseller and printer. By 1861, when he was fifty, he controlled 10% of all newspaper sales outside London. He was a real entrepreneur and he extended his business to take on the  Heywood Print Shop, Oldham Streetprinting of wallpaper and insurance sales and opened overseas branches. Throughout this he retained his radical opinions and supported the Chartist movement although he was against any form of violence. At the same time he played an increasing part in the community. For a long time he was a special constable, demonstrating his non-violent approach to politics. He served on numerous committees and organisations both independent and part of local government. Ragged Schools, Public Library, People’s Dispensaries, sewers, parks, trams and the co-operative movement.

Heywood Print Shop, Oldham Streetprinting of wallpaper and insurance sales and opened overseas branches. Throughout this he retained his radical opinions and supported the Chartist movement although he was against any form of violence. At the same time he played an increasing part in the community. For a long time he was a special constable, demonstrating his non-violent approach to politics. He served on numerous committees and organisations both independent and part of local government. Ragged Schools, Public Library, People’s Dispensaries, sewers, parks, trams and the co-operative movement.

As a result of all this civic service he was made mayor in 1862 at a critical time. The American Civil War had started the previous year and the cotton famine was really beginning to bite. Heywood was instrumental in setting up the Manchester Central Relief Committee, composed of mayors of the affected towns and both money and other forms of relief were collected and distributed. But this did not consume all his time. The city had expanded at an exponential rate and the first town hall, in King Street, although only built in 1825, was far too small for the growing metropolis.

Planning began in 1863 and the requirement was stated as:- “Equal if not superior, to any similar building in the country at any cost which may be reasonably required.” Virtually every architect in the country felt that they could do justice to such a commission and 137 entries were received. These were whittled down to eight finalists and the eventual winner was Alfred Waterhouse. His proposal was only placed fourth in terms of design and aesthetics but it was easily superior for its architectural quality, layout and the use of light. However, perhaps as a consolation prize because he was a Manchester man, certain elements of Thomas Worthington’s design were incorporated in the building, particularly the clock tower.

Abel HeywoodThroughout the construction of the building, although he was no longer mayor, Abel Heywood visited the site almost every day and took part in most of the many decisions that had to be made during construction. The building was estimated to cost half a million pounds but, like many similar projects, it far outran its budget and the final cost was nearer to one million pounds. Still, it was a magnificent building and it was surely appropriate that it should be opened by Queen Victoria. Abel Heywood had been appointed mayor for a second term in recognition of his services to Manchester and, in particular, because of his close association with the new town hall. However, when the invitation was sent to the queen to perform the opening ceremony, she refused. Whilst no reason was publicly stated, it was widely believed that this was because of Heywood’s radical past.

Abel HeywoodThroughout the construction of the building, although he was no longer mayor, Abel Heywood visited the site almost every day and took part in most of the many decisions that had to be made during construction. The building was estimated to cost half a million pounds but, like many similar projects, it far outran its budget and the final cost was nearer to one million pounds. Still, it was a magnificent building and it was surely appropriate that it should be opened by Queen Victoria. Abel Heywood had been appointed mayor for a second term in recognition of his services to Manchester and, in particular, because of his close association with the new town hall. However, when the invitation was sent to the queen to perform the opening ceremony, she refused. Whilst no reason was publicly stated, it was widely believed that this was because of Heywood’s radical past.

Manchester, being Manchester, did not take the snub lying down. If the Queen wouldn’t do it, go to the best alternative - Abel Heywood of course. So it was that on the 15th September 1877 Abel Heywood presided over celebrations lasting three days. The official opening on the first day, Ball on the second and then on the third day, a parade of 69 trade societies, a procession which took three hours to pass by.

This must have been the high point of his life but he was made a Freeman of Manchester in 1891, two years before he died, only the third person to receive the honour. Not just that but the largest bell in the clock tower is named Great Abel in his honour. Not every mayor has an eight ton bell named after him. Eat your heart out, Andy Burnham.

Neil Mullineux, November 2019

Manchester Town Hall Ground Floor Plan. Dated 20th November 1868