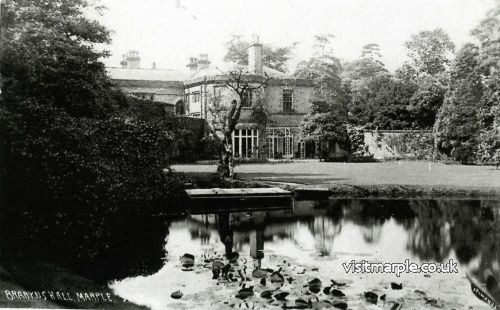

Miss Fanny Hudson and a small group of staff at the rear of Brabyns Hall.

No date on this one but Miss Hudson looks tired and frail

Note: Jack Bradbury, also a native of Compstall, has always lived in the village. He began working in Compstall Mill, but went on to be a gardener, in which occupation he ended his working life. He was now in his 80's, at the time of recording his memories.

Are ya ready? Well, I’ve just arrived here to you now. I’ve been across at (doctor?)Hastings. I’ve bin havin' a good bunfire. Now I’ll just tell you about St. Martin’s, the school. Course in them days, you know, we had to take school money, 2d a week. Mr Hallam, ‘e were the school master, Mrs Raine from Marple, there was Trixie Smith, Minnie Howard, they were teachers at the same time as we were there. Then, of course, they were very strict with us. We had to go to St. Martin’s to the choir to have a practice on a Wednesday Morning and on a Sunday we had to go to church whether we wanted it or not. The Minister at St Martin’s was Mr Hickson, the Reverend Hickson, and old Miss Hudson that’s Miss Fan’s aunty, she was the owner of the Brabyns at the time. She would come and give prizes for scripture once a year for those who could read the scriptures. I think I was about the only one that got a prize for scripture and I’ve still got it at home yet. Take it on the whole there were some good happy days. We got a tea party and she was there as give us a right good time every Christmas.

As the years went by we had t o leave and I went to work in half time at Compstall Mill, (left) learning piecing. When I went down to see about it the boss was called Joe Swindells, so of course he says “Aye lad come in morning.” He says “We’ll see what we can do for thee.” So I went down for 6 o’clock, morning and he took me to little Jack Smith, he were a barber up at Beacom them days. He put me learning piecing there so I had to go to school for half a day and go to mill half a day. I got half a crown a week that were all we got. So anyway, the week after we went for 1 o'clock till half past five and still got half a crown. I’d done about three months and then he put me little piecing for little Jack Hadfield, ya know. Anyway I was with Jack awhile and then I was sent to Jim Bob Kersey. I were there about two year, then he put me big piecing and I was sent on to Tom Wood and old John Waters from Compstall. So I was there till I got with Jim Green, big piecing. Hadn’t we had some happy days I’ll tell you. Course, since I say we can’t grumble but, taken on the whole. in my opinion they were better days than they are today though they were long hours and little money.

o leave and I went to work in half time at Compstall Mill, (left) learning piecing. When I went down to see about it the boss was called Joe Swindells, so of course he says “Aye lad come in morning.” He says “We’ll see what we can do for thee.” So I went down for 6 o’clock, morning and he took me to little Jack Smith, he were a barber up at Beacom them days. He put me learning piecing there so I had to go to school for half a day and go to mill half a day. I got half a crown a week that were all we got. So anyway, the week after we went for 1 o'clock till half past five and still got half a crown. I’d done about three months and then he put me little piecing for little Jack Hadfield, ya know. Anyway I was with Jack awhile and then I was sent to Jim Bob Kersey. I were there about two year, then he put me big piecing and I was sent on to Tom Wood and old John Waters from Compstall. So I was there till I got with Jim Green, big piecing. Hadn’t we had some happy days I’ll tell you. Course, since I say we can’t grumble but, taken on the whole. in my opinion they were better days than they are today though they were long hours and little money.

Still, we have to go with the times and from there we come to the Army 1914, so me and Albert Bradley, we took us out and said we were going joining up. So we went to Stockport. They sent us to Cheshire but they sent us back because we were piecers and had to be exempt. So we were exempt for a while and then we went under Lord Derby’s scheme. Of course, when we went under that, one Sunday morning at Compstall Gardens, Renny Thornley was the man for recruiting. Charlie Dickinson were there and all of the village of a certain age had to go. Of course I went down with the lot so me and Bradley we got A1. We got us shilling so we said we’d be notified of where we had to go. Of course there was Jack Petty, Harry Petty, Sam Petty, Billy Verity, oh there were a right good crew of us. Of course they all got jitters them lot did cos they thought they’d have to go. So anyway some of em seen specialist and said they weren’t fit. One went to London anyway, he got away. Jack Petty and few more of em had to go. Jack was butchering in France. He had a right good job and he come out of it alright.

Still, we have to go with the times and from there we come to the Army 1914, so me and Albert Bradley, we took us out and said we were going joining up. So we went to Stockport. They sent us to Cheshire but they sent us back because we were piecers and had to be exempt. So we were exempt for a while and then we went under Lord Derby’s scheme. Of course, when we went under that, one Sunday morning at Compstall Gardens, Renny Thornley was the man for recruiting. Charlie Dickinson were there and all of the village of a certain age had to go. Of course I went down with the lot so me and Bradley we got A1. We got us shilling so we said we’d be notified of where we had to go. Of course there was Jack Petty, Harry Petty, Sam Petty, Billy Verity, oh there were a right good crew of us. Of course they all got jitters them lot did cos they thought they’d have to go. So anyway some of em seen specialist and said they weren’t fit. One went to London anyway, he got away. Jack Petty and few more of em had to go. Jack was butchering in France. He had a right good job and he come out of it alright. So we went to Stockport, come back and they said we had to stay piecing. So anyway we hung on for a while and then went with Derby’s scheme. Me and a few others had to go to Normanton Barracks at Derby for another exam. So anyway we all went there and only two of us come back. They all got A1 and I got C3 with another one from New Mills. So they transferred me, and this New Mills, man to Buxton and there I was put in a cellar, mixing stew. They give us a blanket to sleep on till we got another medical exam. Then of course from there we had to go back to Derby and we had another medical exam so I was kept another three days. Then I had to have one the next day. They put me through it. I didn’t know what they were talking about but anyway I got me ticket, had to go home and go on munitions. So a big bully of a Captain comes up. He said, “Aye, you’ll be dead lad in twelve months” and I said, “Tha might be shot before me.” Of course he said something nasty ya know but of course I took it I had one on ‘im so anyway I came back. I was sent to Belsize, Manchester and I was there on 4.5’s, (4.5" Howitzer?) (right) loading those till the war were over.

So we went to Stockport, come back and they said we had to stay piecing. So anyway we hung on for a while and then went with Derby’s scheme. Me and a few others had to go to Normanton Barracks at Derby for another exam. So anyway we all went there and only two of us come back. They all got A1 and I got C3 with another one from New Mills. So they transferred me, and this New Mills, man to Buxton and there I was put in a cellar, mixing stew. They give us a blanket to sleep on till we got another medical exam. Then of course from there we had to go back to Derby and we had another medical exam so I was kept another three days. Then I had to have one the next day. They put me through it. I didn’t know what they were talking about but anyway I got me ticket, had to go home and go on munitions. So a big bully of a Captain comes up. He said, “Aye, you’ll be dead lad in twelve months” and I said, “Tha might be shot before me.” Of course he said something nasty ya know but of course I took it I had one on ‘im so anyway I came back. I was sent to Belsize, Manchester and I was there on 4.5’s, (4.5" Howitzer?) (right) loading those till the war were over.

So then when the war were over, of course we had to do the best we could then because everybody were out of work. They wanted me go back to the mill so I went down and took me can, box and me breakfast. I wasn’t in half an hour, so I come out and I chucked the can and box spinning drawers and all the lot over the river bridge. I never seen the mill since. It’s funny isn’t it? So anyway, I thought, “Well what am I going to do now?” Anyway I got on at Gorton Tank under a foreman called George. What was he called? I’ll tell you in a minute, George Hunt. I was under him for about 18 months. Then of course when the Armistice come we’d all finished absolutely, so we are all out of work.

One morning I were coming up Marple to go to the Union office when old Beaton at the Brabyns (above) shouted at me. He said, “Hey lad, art thou out o’ work?” I said, “Aye, I come out last week. “ “Well,” he said, “anyway come and get a wagon o’ coal in for Miss Hudson” “Righto.” So he says, “Come on, come on back with me, ya’ll be alright.” So I went back with him and I got 15 ton in, Marsland brought it down, he were the carter then, in box carts. So of course I stack this ere up and she says to me, “Would ya like go in the garden for a week or two?” I said, “I don’t mind, I’ll go in.” He says, “Can ya dig?” I said, “I can use a pick and shovel and I can do a bit of gardening right enough but I’m not an expert at it.” So anyway I went and did a month. There were me, Tom Bancroft, Beaton and John Hardern up here, one or two more. So anyway when me month were up, Saturday morning, Beaton took me up expecting to finish. She say, “Would you like to stay here?” So I say, “Yes I’ll stay with yer.” I signed an agreement with her for three years. He learned me practically because he were a sick man. If I take on three years because you’d have to insure me do ya see, so of course I took it on and I stayed with her. I was with her for just over four years. I were underman. Then I left her and I went to Springwood but we’d some happy days, t here was no doubt about it.

here was no doubt about it.

Major Charlie, come once he got the VC In the First World War, ya know. He wouldn’t have Brabyns. He came round one day, talking, “I’m not going to have this place, my wife won’t settle here.” Then Captain Willey came from down south, ya know, and then there was Miss Ruth and during the summer we had the McDonalds from Scotland ya know. Used to go with truck up to the station and fetch the luggage down. I always got half a sovereign in them days. You don’t get it today. Old Isherwood used to come from Marple Hall with his chauffeur, carriage and horse, for tea. He said to me, “John, put the horse away and feed it well and I’ll call you for when he’s ready for going back.” Of course that was my job, ya know, so I used to get it all ready for ‘im and sometime Beaton say, “You go back with him bring some cuttings, we’re short of greenhouse cuttings ya know.” So I said, “Righto.” I used to go back, take a clothes basket ,had to walk it back then, ya know. They were days then no doubt about it.

The duty first thing in the morning was to go up to the house for the menu for the day. Used to go round to Manley, that were the butler, and see what he wanted out of the garden for the day. Then if we hadn’t got it of course I had to report back to Beaton and then he had to go and get it from Mrs Schofield, in Marple Bridge. So anyway things went on quite normal and then one day Miss Hudson, it was in January, she says now she’s going to treat us all and send us to Belle Vue to have a day out, quite laughable, ya know. So anyway all the outdoor staff, we had to go up first and Beaton says to me, “What day we going to have?” “Well,” I said, “it’s up to you, anytime will suit me.” So we made arrangements. It was in November and we’d go to Belle Vue (right) on the 2 o’clock train. There was, I think, eight or nine of us, and she give Beaton £5. That were to pay for train fares and teas and have a go on one or two what were going on. The amusing part of it she was expecting some change back when we got back. So Beaton says to me, “What are we going to do Jack?,” “Oh,” I said, “Spend the devil.” I said, “It’s not much.” So he took her thrippence back. Anyway, of course she was quite annoyed about it. A fortnight later Manley had to take the indoor staff. We never knew what she give him or what came back, but that didn’t matter.

The duty first thing in the morning was to go up to the house for the menu for the day. Used to go round to Manley, that were the butler, and see what he wanted out of the garden for the day. Then if we hadn’t got it of course I had to report back to Beaton and then he had to go and get it from Mrs Schofield, in Marple Bridge. So anyway things went on quite normal and then one day Miss Hudson, it was in January, she says now she’s going to treat us all and send us to Belle Vue to have a day out, quite laughable, ya know. So anyway all the outdoor staff, we had to go up first and Beaton says to me, “What day we going to have?” “Well,” I said, “it’s up to you, anytime will suit me.” So we made arrangements. It was in November and we’d go to Belle Vue (right) on the 2 o’clock train. There was, I think, eight or nine of us, and she give Beaton £5. That were to pay for train fares and teas and have a go on one or two what were going on. The amusing part of it she was expecting some change back when we got back. So Beaton says to me, “What are we going to do Jack?,” “Oh,” I said, “Spend the devil.” I said, “It’s not much.” So he took her thrippence back. Anyway, of course she was quite annoyed about it. A fortnight later Manley had to take the indoor staff. We never knew what she give him or what came back, but that didn’t matter.

Every morning the staff had to go for prayer for 9 o'clock. When she came down for breakfast they all had to go in the morning room and she said a little prayer. We used to go into the kitchen and what you call having a little lunch, which came in before dinner time. Then after that of course there was a boiler to be looked after, what fed the house with hot water in a little building outside. Then there was a thing you had to clean all the knives and forks with. Then all the boots wanted cleaning and when you’d done them you went down to Beaton then and give him his menu that was wanted for the house. Then of course I had to do my work, what he give me to do, and then maybe coming springtime well we had all the bulbs and all that sort a going on. On the front we had two beautiful peacocks, always knocking about, but anyway one day we found one dead and the mystery was we never knew where the other one went.

Anyway we had a big dane there and something went wrong with it. We got the vet down and of course we had a bonny job getting him to examine what was wrong with it. It had got something in its foot, but anyway eventually we got in and we got it alright. I’ve no doubt there’s a lot of people have seen the dogs’ graveyard. I’ve buried three while I was there. At the top end I think there is two with a stone one and one without up to me leaving Brabyns. We had about twelve or thirteen of us staff. We’d Manley, Butler and his wife, then the cook, two bedroom maids and two scullery maids. Miss Partridge was Miss Hudson’s maid and we had a German sewing maid. Then there was the handyman. Of course. Them days wages was nothing, scullery maids got 5 shilling a week, £1 a month. I don’t know what Manley and them lot got but I was the highest paid man on the job because I didn’t live on the job. I carried on with her 'till old Beaton died and that was in 1926 and when he passed away. I couldn’t settle so I thought about the only thing I could do now is to get away. So I went to be Head Gardener at Springwood Hall (above) and I had three men there for about two years and then he went bankrupt. He were a builder and contractor in town and then of course I stayed with him till everything was sold and squared out. Then he went to Disley in a small cottage and he squared up with me. He were a gentlemen with me, I’ll admit that, and then I came home. I had only been married eight months then and I was at Springwood Hall at the time. But it was laughable that morning I got married. I had to go to my work the same at 7 o’clock, get to the post office, take the letters up, the papers, look to me two ponies for the girls. Then care for him, take him his shaving water, to the bedroom door. I says I did all that, then I looked to me hens and me ducks and me greenhouses. I come away at 12.00’clock to be married and the beauty of it were he give me a present, a clothes basket full of pots and I had to carry them home. Talk about laughing, I got them home alright, but anyway, just as I was getting ready the taxi come for me, course I'd neither washed nor shaved so I sent him for me brother at Mill Brow. By the time he got back I was ready and I had to go back again at half past five to look to me ponies, lock all up and everything. I had to be there next morning at 7.0’clock. They don’t know they’re born today. The gentleman at Springwood Hall was Major Norquist.

So I went to be Head Gardener at Springwood Hall (above) and I had three men there for about two years and then he went bankrupt. He were a builder and contractor in town and then of course I stayed with him till everything was sold and squared out. Then he went to Disley in a small cottage and he squared up with me. He were a gentlemen with me, I’ll admit that, and then I came home. I had only been married eight months then and I was at Springwood Hall at the time. But it was laughable that morning I got married. I had to go to my work the same at 7 o’clock, get to the post office, take the letters up, the papers, look to me two ponies for the girls. Then care for him, take him his shaving water, to the bedroom door. I says I did all that, then I looked to me hens and me ducks and me greenhouses. I come away at 12.00’clock to be married and the beauty of it were he give me a present, a clothes basket full of pots and I had to carry them home. Talk about laughing, I got them home alright, but anyway, just as I was getting ready the taxi come for me, course I'd neither washed nor shaved so I sent him for me brother at Mill Brow. By the time he got back I was ready and I had to go back again at half past five to look to me ponies, lock all up and everything. I had to be there next morning at 7.0’clock. They don’t know they’re born today. The gentleman at Springwood Hall was Major Norquist.

When it was Compstall Wakes I can remember, when you come to think about it, there was down the Old Coal Pit Lane a Grand Wakes as we had there. Coming up the lane was coconut stalls, brandy snap stalls, front of the Northumberland Arms, Georgia town, dobby horses and all sorts going on. All those are gone by. It really is a great pity we haven’t got it going at the present day. When you come to think, Friday night we used to go down and we all got a free ride to start off with. That was his programme for everybody been helping im pulling about and fixing up, we all got a free ride. But you know, when you think at it, halfpenny on the dobby horses, a penny coconut, twopence for a bag full of brandy snaps and right good time we had. It was on a good week and then when it was gone away it went to Hatherlow and it used to go round from Hatherlow to New Mills, then New Mills to Disley, all following the wakes, week after week.

When it was Compstall Wakes I can remember, when you come to think about it, there was down the Old Coal Pit Lane a Grand Wakes as we had there. Coming up the lane was coconut stalls, brandy snap stalls, front of the Northumberland Arms, Georgia town, dobby horses and all sorts going on. All those are gone by. It really is a great pity we haven’t got it going at the present day. When you come to think, Friday night we used to go down and we all got a free ride to start off with. That was his programme for everybody been helping im pulling about and fixing up, we all got a free ride. But you know, when you think at it, halfpenny on the dobby horses, a penny coconut, twopence for a bag full of brandy snaps and right good time we had. It was on a good week and then when it was gone away it went to Hatherlow and it used to go round from Hatherlow to New Mills, then New Mills to Disley, all following the wakes, week after week.

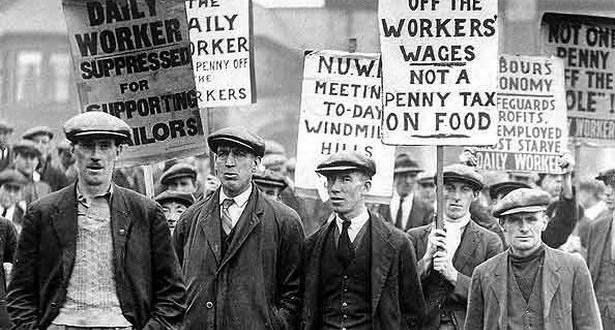

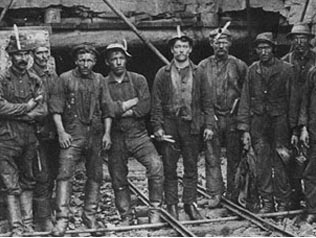

1926 (General Srike) were the Coal Strike and there was no doubt about it, it were the best summer we ever had. I know I was carrying water from June up to November, no rain what ever and I think that’s what broke the colliers’ heart with being a dry summer. They started getting coal out at the recreation ground that’s in Ludworth. There a chap was a chap called Donkey Jones, he used to work for Hudsons, big labourer there and then there was about five of 'em came from Bradford Pit. They were all running this 'ere, getting coal from underneath and running it across in little trucks to the gas works. So one day I were up there, having a look round, and Donkey Jones say, “Would you like to look under?” I says, “I don’t mind, I’ll have a go.” “Well,” he says, “ Tha might not come out my lad.” I said, “It doesna matter, I’ll chance it and if I goes down tha goes down.” So he give me a lamp and I went under with him. I was rather surprised, there were two of em picking up slack coal and doing different parts of it. How dry it was under there, and the pillars, well I couldn’t say how many feet square they was. There was no wooden prop, and you went further on there was another good big pillar. You went further on again and I went under Glossop Road. Well, I should think we came out underneath Lane Ends as far as I can say but of course when you are under there some parts we could walk about. After the war was over, after the coal strike were over, well of course it had to be closed. Then all the lines were took up and the trucks were took back to the gas works. I have wondered many a times whether that place is full of water as shoving the Castle Brow out because it must 've got in somewhere they’ve made it up. I think sometimes if they’d only opened. I am afraid it would come. It must be full of water because it opened out up at Devils Elba (Elbow), the time being where the reservoirs was going up to Sun Hill. Well, two or three bungalows, the first on the left hand side going up. A young fella called, what was he called now, working at, I’ll tell ya in a minute. The first bungalow was Mr Hyde and across the road in the hollow there they opened out and they got underneath there for coal again. They was coming out up bi Georges Wood's at the Ernocroft but they got stopped on account of the reservoirs, afraid less they touched the springs , so that had to be closed. On the whole I was surprised what coal there was to be gotten and there is today. The only thing is, if they’d only investigate more I’m afraid where Windsor Castle is, that’s my opinion there is water underneath, but nobody seems to bother about it.

no rain what ever and I think that’s what broke the colliers’ heart with being a dry summer. They started getting coal out at the recreation ground that’s in Ludworth. There a chap was a chap called Donkey Jones, he used to work for Hudsons, big labourer there and then there was about five of 'em came from Bradford Pit. They were all running this 'ere, getting coal from underneath and running it across in little trucks to the gas works. So one day I were up there, having a look round, and Donkey Jones say, “Would you like to look under?” I says, “I don’t mind, I’ll have a go.” “Well,” he says, “ Tha might not come out my lad.” I said, “It doesna matter, I’ll chance it and if I goes down tha goes down.” So he give me a lamp and I went under with him. I was rather surprised, there were two of em picking up slack coal and doing different parts of it. How dry it was under there, and the pillars, well I couldn’t say how many feet square they was. There was no wooden prop, and you went further on there was another good big pillar. You went further on again and I went under Glossop Road. Well, I should think we came out underneath Lane Ends as far as I can say but of course when you are under there some parts we could walk about. After the war was over, after the coal strike were over, well of course it had to be closed. Then all the lines were took up and the trucks were took back to the gas works. I have wondered many a times whether that place is full of water as shoving the Castle Brow out because it must 've got in somewhere they’ve made it up. I think sometimes if they’d only opened. I am afraid it would come. It must be full of water because it opened out up at Devils Elba (Elbow), the time being where the reservoirs was going up to Sun Hill. Well, two or three bungalows, the first on the left hand side going up. A young fella called, what was he called now, working at, I’ll tell ya in a minute. The first bungalow was Mr Hyde and across the road in the hollow there they opened out and they got underneath there for coal again. They was coming out up bi Georges Wood's at the Ernocroft but they got stopped on account of the reservoirs, afraid less they touched the springs , so that had to be closed. On the whole I was surprised what coal there was to be gotten and there is today. The only thing is, if they’d only investigate more I’m afraid where Windsor Castle is, that’s my opinion there is water underneath, but nobody seems to bother about it.

Apart from that, ya Small Coal Mine know, Charley Dickinson was the landlord at Compstall Gardens. Course we know what Charley was, he was all dibbing in wireless sets and one thing or another. So hauliers opened a coal mine down in’t wood, sure there was coal there was gonna make a fortune. So anyway he got some of these trucks and one or two of these men had come down with these trucks. They made a road down into the wood, they dug a big hole and then they got one of these pulleys and let themselves down in buckets.They were at that job for weeks and weeks and Charley were saying we’ll be on coal in a bit on the shale now so he got below the river. Anyway, three or four of us say we’ll do it on Charley, so we went one night and they got some slack coal out of one or two coal houses. We took in a bag over by yonder, went through the wood and dropped it down. So when they went next morning, it were all over village shouting, “ We’ve found coal.” They were well away.

Small Coal Mine know, Charley Dickinson was the landlord at Compstall Gardens. Course we know what Charley was, he was all dibbing in wireless sets and one thing or another. So hauliers opened a coal mine down in’t wood, sure there was coal there was gonna make a fortune. So anyway he got some of these trucks and one or two of these men had come down with these trucks. They made a road down into the wood, they dug a big hole and then they got one of these pulleys and let themselves down in buckets.They were at that job for weeks and weeks and Charley were saying we’ll be on coal in a bit on the shale now so he got below the river. Anyway, three or four of us say we’ll do it on Charley, so we went one night and they got some slack coal out of one or two coal houses. We took in a bag over by yonder, went through the wood and dropped it down. So when they went next morning, it were all over village shouting, “ We’ve found coal.” They were well away.

I think it was 1923 or 4, I couldn’t just say for the date, but there were two or three accidents within 10 days there. I was coming out one dinner time for dinner, there was a terrible bang and a big lorry come down with timber and it shot in Old Wood's little shop. (pictured below, little boy inspecting another crash) He had a drapery shop at the time and he used to go round with a pack selling drapery. His daughter were in the shop and of course this was well in. Well, of course I looked at the cab. The driver was stuck inside and I could see he were alright. So, anyway, I got round into a corner after Miss Wood, and I got her out. She was badly shaken and I thought she had some limbs broken but she hadn’t. They took her across to Dr Hibbert’s at the time. Anyway they took her to the infirmary but brought her back next day. S Mrs Woods shophe were badly shaken. The driver was badly shaken and just a bit crushed but not badly hurt. So they got the lorry out and all was patched up.

Mrs Woods shophe were badly shaken. The driver was badly shaken and just a bit crushed but not badly hurt. So they got the lorry out and all was patched up.

Then a week after, I’m coming out again on the Monday dinnertime for me dinner and old John Yarwood, carrier at Marple Station, used to go up there with horse and lorry, taking all the parcels out for the railway. So whether it bolted, or what , coming down the brow, we don’t know, but I was just coming out by Beatons when down it goes into the bottom where those railings were for steps to go down into those two cottages. Well, he were underneath the horse, the horse was on its back, the lorry and the lot and he were underneath it. So of course, four or five of us, we got him out best way we could. We thought, well we knew he were dead alright, so what did we do of course we never thought anything. There were four of us so we’d take him over the bridge and take him home. Anyway police come after us and they took him back again. He were on Marple side, so anyway took him to Jub’s, that was the public house at the time, The Midland. They took him there. Of course it wouldn’t be alright doing that. We said we didn’t know, we did it for the best, but anyway they had to shoot the horse and clear it all out. Anyway they found out it was accidental death but they don’t know really whether it was the horse or what had done it. He were badly crushed.

So that squared that up and then it come to the alterations. Brabyns Brow had to be widened after that and nothing about it. Dr Hibbert’s house had to come down you see. Anyway it went on for a while and that came down. They widened that corner there so that went on for a few year or two. Joe Pover’s (Horseshoe) had to come down at the bottom. They said that public house was a dark horse so that came down. Then Miss Yarwood had her old shop and cottages pulled down and had the shops put there what are there now. She kept the one as an ironmonger’s until she retired from business. So all that was done and then we saw the bridge widened by the County. That was a big improvement but I think if they had took it on the other side as wide as they’d done there , there wouldn’t be the trouble there is today and it would have been a lot cheaper but whether it will get done I don’t know.

Biil Beard, Ruth Hargreaves and Louise Thistleton