Keith Denerley lived in Marple during the Second World War and his memories of that time cast a fascinating light on everyday life during a very difficult period. He went on to become a vicar and never returned to live in Marple. Keith says:

Reminiscing about Marple in the 1940’s with a friend recently, she thought I ought to set such things down, so here goes.

All Saints' School on Church Lane

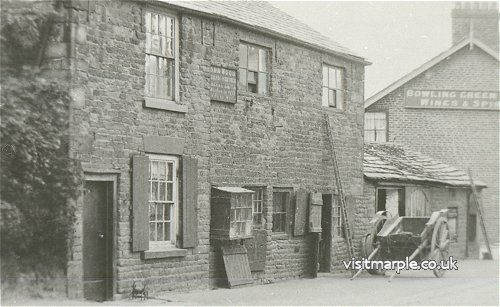

My parents, sister and I moved from Didsbury Road, Stockport, early in the war, as the house (Richmond Lodge) where we lived was next to some railway marshalling yards, a favorite target of enemy bombers. My father had a chemist’s shop on Brinksway, Stockport, and also one on Stockport Road, Marple, that I believe is still there. We lived above the shop. There was a post office next door (where the son rejoiced in an O gauge electric railway), and a garage opposite. The “garage opposite”, Yeates Garage photographed in the 1950s but still there today.This garage had petrol pumps painted plain grey, with the legend “Pool Petrol”, and I found it very strange to be told that in peace time there were many different brands of motor fuel – I couldn’t think why. Of course petrol was severely rationed during the war, which limited local buses to a single route, the 27X I think, from Hayfield to Manchester - always operated by one of those squashed double deckers that would fit under low bridges. It was nearly always standing room only – Dad actually worked in his main shop on Brinksway, Stockport (now under the M62), and if the last bus home was full, he would walk home. Mum told me she would go to meet him, and hear his whistle from afar as he marched up Marple Brook to Rose Hill.

The “garage opposite”, Yeates Garage photographed in the 1950s but still there today.This garage had petrol pumps painted plain grey, with the legend “Pool Petrol”, and I found it very strange to be told that in peace time there were many different brands of motor fuel – I couldn’t think why. Of course petrol was severely rationed during the war, which limited local buses to a single route, the 27X I think, from Hayfield to Manchester - always operated by one of those squashed double deckers that would fit under low bridges. It was nearly always standing room only – Dad actually worked in his main shop on Brinksway, Stockport (now under the M62), and if the last bus home was full, he would walk home. Mum told me she would go to meet him, and hear his whistle from afar as he marched up Marple Brook to Rose Hill.

We did have a car ride once when, after his hernia operation, Dad got a grant of petrol to go for a holiday in St Anne’s. I remember his excitement when we were “topping 50” on a straight length of road. There was one car that sported a large gas bag on its roof for fuel (its owner was thought to be a spiv), and some buses towed a small two-wheeled trailer that was reputed to be some sort of charcoal burner. Otherwise, it was horse and cart. Oh! The thrill of being invited up on to the milk float, from which the milkman dispensed the white stuff into customers’ jugs with a ladle from the churn, and waving down to friends still on the pavement as we trotted past. And when one whole day Dad turned up with a borrowed pony and trap, and took us picnicking around Disley, we were in the seventh heaven.

Horses of course came into their own as abundant fuel grew locally. I watched fascinated as they were fitted with their metal shoes at the local smithy at the bottom of the road, where it joins Church Street. (Ed. Church Lane) My picture is of a shed open on one side, underneath a great chestnut tree - but I may be being influenced by Longfellow’s poem. Certainly the smith was a mighty man, hammering the white hot metal on his anvil, and then amazingly fitting it still sizzling to the hoof, the animal not seeming to turn a hair.

A close up view of Norbury Smithy, Stockport Road.

The sign above the door said 'John Wood, Horse Shoer, General Smith, Dealer in all kinds of Nails'. (The Smithy is the single storey shed above. Keith was correct about the open shed but where is the spreading chestnut tree? The photo is early 1900s so I guess the spreading chestnut tree was a mere sapling – Hilary Atkinson.)

There was a sort of open space I think near the smithy, and here at the end of the war the army stationed several trailers with the amazing radar installations that had been so useful in the Battle of Britain. We could go inside and watch the ghostly green radial cursor on the cathode ray tube bleeping when it struck an object, and look outside to the revolving aerial dish on the roof of the van. Earlier, I remember the army marching through the village, military band and all, on what was I suppose a recruitment drive for the “42nd Cheshires”.

Other parades used to happen at Whitsuntide (the weekend secularlsed by Harold Wilson), when the Sunday schools would turn out complete with band and a huge banner, that took two stocky men to support the poles, and four others to hold guy ropes fore and aft; followed by boys in their best shorts and white shirts, and girls In summer dresses. My sister went to the Methodist Sunday school on Market Street, where the Queen of the May would process with her retinue, two flower girls strewing rose petals in her path.

I only went to Sunday school once, where the minister spoke about peace inside the church, and the boys fought on the way back. But I did take school assembly seriously: I remember a certain feeling of satisfaction when I realised I could sing every verse of “O worship the King” from memory; and another time when the pupil next to me in assembly said they liked standing there because of the way I said the Lord’s Prayer. Foretaste of things to come!

All Saints’ CE school was at the top of Church Street (Ed. Church Lane) , up the hill and over the canal bridge. This bridge sprouted small square manhole covers, that we were told could harbour explosives in case of invasion, moreover to the side appeared collections of concrete cylinders we were told were “tank traps”, as apparently any tracked vehicle attempting to surmount them would find itself out of control. (Ed. For a long time the concrete cylinders were alongside the canal at Marple Wharf but are now gone.) I’m told the school is still there, I expect it has lots of Portakabins in the playgrounds (boys to the right, girls and infants to the left). In our day it was a standard Victorian building with high windows (“keep your mind on the job”) and a hall that would take 60 or so desks (iron framed, lifting lid and seat, inkwell). These were divided into two classes by 6’ moveable partitions, so that you could hear what the other class was doing, though I don’t remember it being a distraction. Other classrooms had wood and glass partitions that went up to the ceiling.

The wartime tank traps when they were still at Marple Wharf

Every morning we had five minutes chanting multiplication tables 2 to 12, then various lessons, exercises and so on; and no talking in class. My mother, a teacher herself, told me she was always getting caned for talking during lessons in her time – not that she was ever reticent in later life!

The headmaster had a corner of one classroom partitioned off – when we were naughty, we had to go and stand outside, then he would appear with a strap or a cane, and whack the flat of our hands – 1, 2, 3 or 4, after which we hoped no one would “tell on us” to our parents, who would have administered further punishment!

No such thing as school meals – we walked a mile or so each way for dinner (lunch) each day. There was a “British Restaurant” half way up the hill, providing off-ration meals. We went there occasionally, I don’t know why, and had shepherd’s pie with a basis of gristly meat, that has left me with a lifelong suspicion of mince. (See Note at end about British Restaurants.) At school we were issued with 1/3 pint of milk halfway through each morning. It came in individual bottles with cardboard tops; each top had a perforated hole that you had to press down, and I think we had straws to insert – otherwise, a finger would lift out the card circle, and you drank from the bottle.

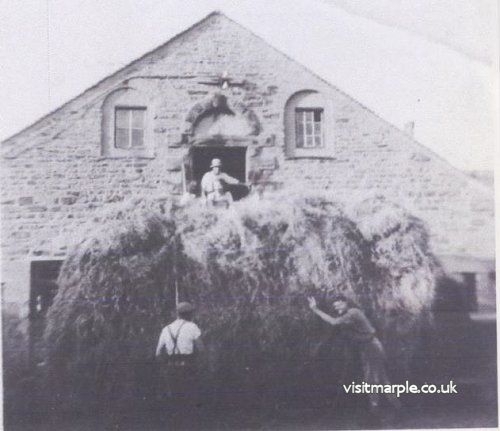

Haymaking at Chapel House Farm in 1953.I never went myself, but each autumn you were allowed a week or two off school to go potato picking, I suppose it was a country custom, and/or part of the war effort. Some years, we were taken to watch the threshing machine at a local farm: a great wooden thing with wheels and holes everywhere, powered by a stationary steam engine that drove a belt that mysteriously clung to two rimless driving wheels. A man perched atop the contraption tipped sheaves down a chute, whilst others fixed sacks to the sides to catch the grain, whilst straw was miraculously ejected in bales at the back. Earlier, we had watched stooks of corn in the fields being loaded onto flat wagons by men with pitchforks, the man on top being lifted higher and higher, whilst the horse waited patiently to tow the wagon to the barn.

Haymaking at Chapel House Farm in 1953.I never went myself, but each autumn you were allowed a week or two off school to go potato picking, I suppose it was a country custom, and/or part of the war effort. Some years, we were taken to watch the threshing machine at a local farm: a great wooden thing with wheels and holes everywhere, powered by a stationary steam engine that drove a belt that mysteriously clung to two rimless driving wheels. A man perched atop the contraption tipped sheaves down a chute, whilst others fixed sacks to the sides to catch the grain, whilst straw was miraculously ejected in bales at the back. Earlier, we had watched stooks of corn in the fields being loaded onto flat wagons by men with pitchforks, the man on top being lifted higher and higher, whilst the horse waited patiently to tow the wagon to the barn.

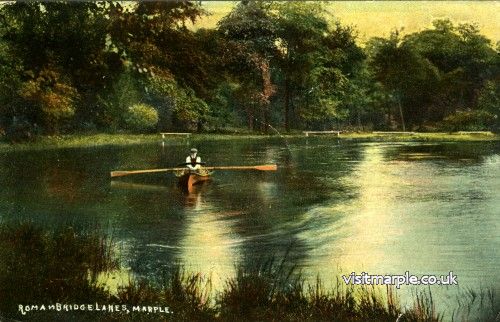

After school, quite often Mummy would meet me along with my sister in the pushchair, and Dad would come too on Wednesdays, which were half days for him. We would go long walks, maybe along the canals with which Marple is well supplied, maybe up towards Whaley Bridge, or out past Goyt Mill, or down past the locks as far as the great aqueduct and viaduct over the Goyt valley. Other days it might be to the waterfall and ford further down the river, or along Strines road the other way, and over the “Roman” bridge that always looked so flimsy, and down past another fearsome waterfall topped by a railway bridge. Near here was what had been a tearoom I was told, patronised by my parents in their courting days. And then, the boating lake, with an ice cream if we were lucky, or a Jewsbury and Brown grapefruit crush and a boating trip where Mother taught me to row. This last lesson I had completely forgotten about when many years later I rowed for my Oxford college. One vacation I was at home explaining the technique of feathering the blade, and got some very strange looks when I asked “Can you row, Mummy?!” It became a family joke often repeated in company to embarrass me.

A hand coloured card of a lone rower on Roman Lakes.A favourite walk was through the grounds of Marple Hall, stopping on the way to peer into a pond by the wayside. From this for several years we would collect frogspawn in jam jars with string round the rim .It looked like tapioca pudding with black bits in. Mother found some largish glass water tanks in the Wreck, which were old accumulator jars from the time when you ran wireless sets from these large batteries full of acid, that you had to take to the shop every so often to be re-charged. In these we made aquaria, sweetened with pond weed, and fed the tadpoles with scraps of meat. After a month or so they morphed into dear little froglets, for which stones had to be provided for them to get out onto. One year the number of tadpoles kept reducing day by day, until we realised that the one remaining one had eaten all the rest!

A hand coloured card of a lone rower on Roman Lakes.A favourite walk was through the grounds of Marple Hall, stopping on the way to peer into a pond by the wayside. From this for several years we would collect frogspawn in jam jars with string round the rim .It looked like tapioca pudding with black bits in. Mother found some largish glass water tanks in the Wreck, which were old accumulator jars from the time when you ran wireless sets from these large batteries full of acid, that you had to take to the shop every so often to be re-charged. In these we made aquaria, sweetened with pond weed, and fed the tadpoles with scraps of meat. After a month or so they morphed into dear little froglets, for which stones had to be provided for them to get out onto. One year the number of tadpoles kept reducing day by day, until we realised that the one remaining one had eaten all the rest!

Looking back, a great advantage of wartime was that you could walk or cycle for miles along country lanes and never see a car – or hear the noise of traffic for that matter. On the down side, there were the occasional air raids, but to us boys it was a sort of game, reproduced in the playground when we weren’t playing Cops and Robbers or Cowboys and Indians. (How the status of Red Indians has changed!) And when there was a night raid, and the sirens wailed, it was an adventure to get up out of bed and picnic under the stairs (this being the most substantial part of the house). Others had cellars to go down into, or Anderson dugouts in the garden. One year a German aircraft came down up on the moor, and some proud boys turned up next day at school proudly showing bits of shrapnel, or in one case a cartridge case stamped with German Gothic writing.

A V1 flying bomb fell in Adswood, Stockport at 5.30 in the morning of Christmas Eve 1944. (87 Garners Lane)For several years the raiders used to put in an appearance a few days before Christmas, to demoralise us I suppose. You could always recognise their engine noise, it had a slowly pulsating sort of wailing drone, that I’m told was produced by deliberately de-tuning the ignition. More menacing were the “doodlebugs” later on, the pilotless flying bombs, whose enging noise would suddenly stop, followed by a pregnant silence before the bang of the explosion that we always hoped would take place somewhere else (which it did, or I shouldn’t be here). We never suffered the lethal V2 rockets, but going once into Manchester saw a whole street that had been demolished by a single strike. (See note at end about the V1 and V2 weapons)

A V1 flying bomb fell in Adswood, Stockport at 5.30 in the morning of Christmas Eve 1944. (87 Garners Lane)For several years the raiders used to put in an appearance a few days before Christmas, to demoralise us I suppose. You could always recognise their engine noise, it had a slowly pulsating sort of wailing drone, that I’m told was produced by deliberately de-tuning the ignition. More menacing were the “doodlebugs” later on, the pilotless flying bombs, whose enging noise would suddenly stop, followed by a pregnant silence before the bang of the explosion that we always hoped would take place somewhere else (which it did, or I shouldn’t be here). We never suffered the lethal V2 rockets, but going once into Manchester saw a whole street that had been demolished by a single strike. (See note at end about the V1 and V2 weapons)

The nights were very dark, all our windows were covered with blackout curtains. If you showed the merest chink, a Warden would shout “put that light out!” and we would guiltily close the open door. Some windows were covered with a criss-cross of brown sticky tape, so that they wouldn’t splinter in case of bomb blasts. It did mean that we had a good view of the stars, and also were very conscious of phases of the moon. After the war, the first signs of peace were when they lit the pilot lights of the gas lamps in the street, and we went a tour of the village specially to see. Only later were the full gas mantles illuminated.

All food was rationed of course. You had books of coupons that the shopkeeper cut out with a pair of small scissors except for the British Restaurant meals, and the fish and chips shop, where there was always a queue. Not everyone took their full ration of cheese, so my mother often bought extra “under the counter”, and I’m fond of cheese to this day. Only two kinds – the ubiquitous cheddar and a delicious pungent crumbly white we called Cheshire. As to milk, I was often sent to a local farm for extra bottles, that I transported back home hidden in the bottom of my sister’s large pram, she being inside – thus combining entertainment for her with provision for the family.

Behind our terrace was a sizeable triangular area we called the Wreck, short for Recreation Ground. (Ed. The waste land between Stockport Road and Church Lane.) We constructed dens and played various games, mildly organised into gangs. There was a car laid up for the war on blocks, into which we effected entrance and had a great time touring the country, until the owner chased us out.

The area bordered by Highfield Avenue, Union Road and Stockport Road where Keith played.

Local people remember this as the Workshop of a firm called Grandelek, who renovated tv screens. It was sited at the end of Highfield Road, off Union Road. On the back it says "Workshop 1949" so presumably this is when it was built.

We stuck pitch into his keyhole in revenge. One day I borrowed a beautifully made large soap box, a crate really, and took it along to a corner of the playground, and there it became for me a ship sailing the south seas. I landed when it was dinner time, and left it on the shore, but when I came back it was gone, so my adventure ended in a spanking.

Further up the road were the baths, which were boarded over for the duration with a dance floor, where I remember going as a Persian Prince to a fancy dress party of some kind, and winning a prize. My parents were great ballroom dancers, there was a marvellous sense of excitement as they prepared for a ball, Dad is his smart DJ, Mum in a flowing full length gown of emerald green and delightfully perfumed with Eau de Cologne. They told me that they had, in fact, met dancing in a sort of ballroom country formation dance called The Lancers, at the local Palais de Dance in Ashton-under-Lyne.

My mother had started her teaching career, as one did in those days, as an unqualified assistant at the school she had attended herself – talent spotted I suppose – only then did she study at night school for her certificate. A good way of selecting those with talent to control classes of 30+ I think. And she could command silence in a room of youths bigger than and not much younger than herself, (but she couldn’t control me, she would declare from time to time!). The secret, she maintained, is to keep the class’s interest, so they don’t have time for mischief. She did have a cane, as was the custom, but used it sparingly and effectively, and thought it was important as a last resort. She had stopped teaching when she got married, as did all ladies in those days – to make room for younger ones coming up.

Manchester Grammar School - A wrought iron fence runs along the north side of Old Hall Lane in Rusholme and on some of the fence posts you will find perching owls. The owl is the symbol of Manchester Grammar School which lies beyond the fence.

In our final year at All Saints’ we had Intelligence Tests at 11+, which were a sort of series of puzzles, quite fun if you treated them as a game. The key thing was not to spend too long on any one question. I passed for Hyde Grammar School, to which my father had gone before taking up pharmacy – he could still sing the school song “Nunc amici consurgamus” in full, although he didn’t know the meaning. When I later learnt Latin I could translate it for him, so accurate was his memory. However Mum and Dad wanted higher things for me, and entered me for a scholarship at Manchester Grammar School. I had a bad cold on the day of the examination, , so Dad hired a taxi and took me wrapped up on a blanket. We sat the papers in the refectory, on long trestle tables with the scripts arranged alternately. “Couldn’t you see what the other boys had written?” they asked me of the maths paper. “Yes.” “And?” “They were wrong!”

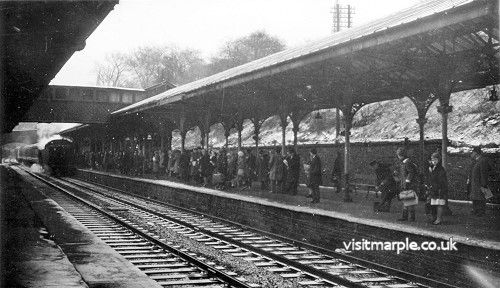

Marple Station 1965, still retaining four platformsManchester and Hyde were both rather further from home than a mile up the hill, but we did stay for school dinners: grey mashed potatoes, horrible gravy, swede, bony rabbit, strong tasting liver, stringy beef, unpickled beet, and a pudding we called “dead baby”. When my mum told me to think of the starving millions of Africa, I had a mental picture of enclosing such things in great envelopes and posting them. The journey to school involved crossing the park to the station, which in those days had four platforms and a wide glass roof, then a train to “Withington and West Didsbury”, then a bus to Fallowfield, and a long walk through the school grounds.

Marple Station 1965, still retaining four platformsManchester and Hyde were both rather further from home than a mile up the hill, but we did stay for school dinners: grey mashed potatoes, horrible gravy, swede, bony rabbit, strong tasting liver, stringy beef, unpickled beet, and a pudding we called “dead baby”. When my mum told me to think of the starving millions of Africa, I had a mental picture of enclosing such things in great envelopes and posting them. The journey to school involved crossing the park to the station, which in those days had four platforms and a wide glass roof, then a train to “Withington and West Didsbury”, then a bus to Fallowfield, and a long walk through the school grounds.

Whereas the train to Hyde consisisted of brown compartment stock hauled by a 4-4-2T engine bound for Manchester London Road (now Piccadilly), ours was maroon corridor stock with a large 2-6-0 going from Buxton to Manchester Central (now an exhibition hall), often crowded with servicemen. I remember sitting on a sailor’s knee for several stops including Stockport Tiviot Dale, which was built out above the confluence of the Erewash and Goyt that makes the River Mersey, now under the M62 again. Tiviot Dale had a pair of bay platforms that held several extra large Cheshire Lines coaches that never seemed to go anywhere.

Much to my dismay, we never had trams anywhere near Marple, but they did run from Stockport to Hyde, and on one memorable occasion I travelled from near Manchester Grammar to Hyde to see my granny. Manchester trams were red and white, with double bogies – I think they could carry 80 passengers; Stockport ones were similar in colour, but with only four wheels, which made them somewhat bouncy. There were four wheeled green trams too, of the “Stalybridge Hyde Mottram and Duckinfield” joint authority, or SHMD for short: these had open galleries fore and aft, above the driver who also had to stand in the open air; these I loved because you could pretend to be driving yourself. I much preferred the glide of the tram to the lurching of the buses, that made me feel rather sick, especially on the upper deck that was always full of tobacco smoke.

Stockport tram passes the Plaza Facade

The terraced house containing the shop was typical of its kind, basically two up two down but extending into the back yard. Upstairs this extension housed a small bathroom and bedroom beyond, whilst below was a sizeable kitchen containing the range built into the far wall. The first job in the morning was to get the coal fire going behind the vertical bars. It threw out a lot of heat and had a hob on one side for a large kettle, a bread oven on the other side with a huge latch, and the hot water boiler behind, invisible except for the sort of semicircular tunnel at the back of the fire. Heating for the oven and boiler was controlled by dampers, a sort of sluice that you operated with pull rods to open and close the flues. Once a week, when cold, the whole thing was polished with a compound called black lead, that made both the black parts and the shiny bare steel sparkle.

A lean-to beyond the kitchen contained the coal hole and the loo, both accessed from outside. I was afraid of the dark, and there being no electric light in the toilet, I was provided with a candle lantern when nocturnal visits were necessary. Otherwise, we all had chamber pots called “gazundas”. The yard was mainly flagged, but had a tree at the far end that I learned was a wigelia, and a herbaceous border. I do remember buying a pot egg in the hardware store down the road, because I liked the shape, and for some reason buried it inside a jam jar – years later I was surprised to read of a similar custom amongst the natives of Easter Island. I also fashioned some “silver bells” from small sticks and a roll of silver paper my aunt had salvaged from her aircraft factory, but when I heard of the sinking of the Ark Royal, and the death of the Archbishop of Canterbury (who sounded very important) I fashioned little black caps to sit atop the bells – foretaste of things to come again?

So – happy days, on the whole, for children. I’ve been back a few times, and naturally it all looks smaller. There’s no great mill on the corner, but the park is still there. Trains still run to Rose Hill, but now reverse back again; the main station on Brabyn’s Brow has lost two platforms and its lovely glass canopy. The magnificent flight of locks is in working order, patronised by many holiday craft in season, but there are houses filling the nearby field down which we used to sledge in winter. Last time we visited, the boating lake in the lovely Goyt valley had replaced boats with line fishermen all round, but you could still walk through into Marple Bridge, or up the hill to the golf course. Strangely, a relative of the my wife, whom I met in my Oxford days, lives just by the golf clubhouse, over against the old Georgian church whose tower stands sentinel over the valley.

Perhaps I’ll sign off by remembering a high spot after the war, when I joined the schoolchildren lining the valley road (Dooley Lane) to cheer on the old King George VI as he drove past in a cavalcade of sleek black limousines. I was proudly sporting the purple blazer of my new school in Halifax, to which Pennine town my parents had moved. He looked rather old and frail, but he and his family had seen us through the war, and we all waved our flags and cheered. God save the King!

Keith Denerley, November 2019

Wartime Footnote:

British Restaurants

Although rationing was brought in very early in the war the government organised a national chain of restaurants where people could buy nourishing meals at low prices. They were set up by the Ministry of Food in 1940 and were only disbanded in 1947. At their peak in 1943, 2160 restaurants all over Britain served 600,000 meals each day. The original intention was to provide for people who had been bombed out of their homes or had run out of ration coupons but they soon took on a political dimension as well, guaranteeing a nourishing diet to the poor.

British Restaurant Poster with direction arrow from WW2 (Source MLHS Archives)

The restaurants were run by local government or voluntary agencies on a non-profit basis. Meals were sold at a maximum price of 9 pence (about £1.70 in today’s purchasing power). The British Restaurant in Marple was in the All Saints’ Parish Hall in Chadwick Street. It was on the corner with Church Street, but it was demolished in the late 1970s and sheltered accommodation built on the site.

V1 and V2 rockets

Although Britain suffered terribly from bombing during WW2, it became less of a problem as the war progressed. With the invasion of Italy in July 1943 and the Normandy landings in July 1944 the Allies were taking the war to continental Europe. However, for the civilian population, the situation changed with the launch of the first V1 flying bombs aimed at south east England a week after D-Day. The first bomb landed at Mile End in London’s East End but it was followed by about 9500 in the following three months. At its peak about 100 were fired each day but by October they had ceased as the launch sites were overun by the Allied army moved across northern France.

Technically the V-1 was a cruise missile or ‘flying bomb’ but it was succeeded by the V-2, the first genuine rocket. Whereas the V-1 flew at a height of under 3000 metres, the V-2 flew at heights up to 170 kms. The first of these rockets was fired at London in September 1944 and in total about 3000 were aimed at London, Antwerp and other cities in Belgium and France. The V-2 carried a similar weight of explosives as the V-1 and was very effective in avoiding defensive countermeasures. However, the problem was its cost; a V-1 could be manufactured for a mere 4% of the cost of a V-2. For every V-2 made, it was possible to make 25 V-1s.

Although the era of these “Vengeance weapons” lasted only for a few months, they had a major impact on the civilian population of the whole country. The Allies had appeared to be winning the war but suddenly these mystery weapons appeared to come from nowhere. Even though the only V-1s and V-2s fell in south east England all areas of the country felt vulnerable, particularly those areas such as Manchester and Liverpool which had suffered so badly from conventional bombing. As a last desperate measure, a few V-1 bombs were launched from German aircraft when the launching sites were overrun. On Christmas Eve 1944 a squadron of Heinkel He 111, flying over the Yorkshire coast, launched 45 flying bombs at Manchester. None actually landed in Manchester itself but 27 people were killed in Oldham by a stray bomb. Another landed in Adswood and two houses were destroyed with several others damaged. Unfortunately there was a fatality, but it could have been much worse.

The picture below, from the Stockport Advertiser, shows the damage.